The Public Conduits of Exeter

Page added 25th June 2018

The Public Conduits of Exeter where, what many historians consider, the most sophisticated medieval public water system in the country. The system was fed by springs in St Sidwells, through lead pipes buried in the ground, and running through the underground passages, to allow maintenance and upgrades.

The first underground aqueduct was installed by the Cathedral authorities–it supplied a third of its water to St Nicholas Priory, a third for the Cathedral through their ‘conduit house’ in the Close, and a third for the citizens who shared the same outlet. In the middle of the 15th Century, the city installed its own pipes and passages to supply water directly to the middle of the High Street by St Lawrence Church. Eventually the system was extended to the Carfax, where they built the Great Conduit.

The Great Conduit

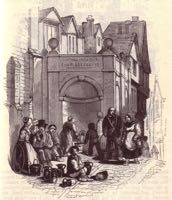

The Great Conduit was constructed in the 1461 when the pipes from the underground passage in the High Street were extended. There are several impressions of the structure on maps, the earliest being Braun and Hogenburg of 1618. However, probably the most accurate representation is from a 19th Century copy by Emmanuel Jeffery, of an 18th Century drawing.

The Great Conduit was not in the middle of the Carfax, but near the top of Fore Street. The outlet pipe was facing away from the Carfax, to allow waste water to run down a gully in the middle of Fore Street. The first structure was fairly simple, but as the years passed, and it needed repairs, stone from Dartmoor was purchased and Cathedral masons were employed in the reconstruction. Jenkins records that it was rebuilt in 1461, by William Duke, Mayor, while records show it was further improved in 1501 and 1535. Many religious motifs were carved into the structure, and there was a statue, possibly of the Virgin Mary over the outlet pipe. At one time, it was ordered that oil paints be used to decorate the stonework, much as the West Front of the Cathedral was once painted. Jenkins described the Great Conduit in its later years thus:

“… it was decorated with pinnacles at the four corners, on which were (anciently) vanes; but they have long since fallen victims to time and weather; there were also niches in the east and west fronts, in which were mutilated statues. On the top of the architrave, at the corners, were two lions and two unicorns… It was likewise adorned with cherubims and armorial bearings, which were so much injured by time that only those of the Courtenay family could be distinguished.”

As the water flow from St Sidwell’s was not very great, internally, the conduit contained a lead cistern, which would fill up overnight, when the conduit was closed from use. Records report a wait of three to four hours to fill the bucket could be incurred–the length of the wait probably increased after a few hours as the cistern ran out and the flow diminished to the rate that the well at St Sidwell’s could supply it. Deliberately situated at the top of Fore Street, citizens would trudge up South, North and Fore Street with their empty buckets, while it was downhill with them full. On the walk home, bucket laden townsfolk would have to be careful where they trod, as the gully running down Fore Street was a favourite place to empty chamber pots–sometimes they were emptied right under the outlet pipe. Brewers and bakers were banned from filling barrels from the pipe, as they would empty the cistern, leaving the ordinary citizen without a supply.

The Great Conduit was also a centre of city life. It was one of the places where a new King was announced, while many important procession from the Guildhall to the Cathedral would proceed up to and pass around the Great Conduit. The conduit ran with wine at the celebration of Charles II taking the throne in 1661. From time to time, choristers would be brought in to sing over the conduit to bless the water.

As the city grew, the position of the Great Conduit in the centre of the street proved a hindrance to traffic. It was taken down in 1770, and rebuilt in the High Street, in front of what is now, McDonalds. However, this was hardly an improved position for the structure and it was removed in 1799 and a new conduit built in South Street.

The South Street Conduit

The new conduit was opened by the Mayor, Jonathan Worthy in 1800. To record this event the conduit was enscribed with "Jonathan Worthy, Esq., Mayor. Charles Collins, Esq , Receiver. 1800." This was a much simpler structure, more utilitarian in design, but still occupying a significant part of the street, outside the College of the Vicars Choral. The supply was not without problems, as the well head at St Sidwell’s could not keep up with demand, and the degradation of the pipes slowed the flow.

For 35 years it remained the main source of clean water for people in and near to South Street. But it too suffered from a failing supply from the well at St Sidwell’s. One correspondent to the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette wrote in1892 of his memories of the conduit:

“The South-street conduit was a notable place. The water was much esteemed, I think, for tea-making. The supply was not abundant, and disputes, ending in fights, were constantly occurring, arising out of the claim as to "turns," of persons preferring to allow their pitchers and pails to remain during their absence, and hence quarrels on their return to fill their vessels.”

The cholera outbreak of 1832 claimed 402 victims, mostly in the West Quarter. Although it was not known at the time, it was the water dippers sourcing water from the leat that spread the disease. Those who used the South Street conduit remained healthy. It was becoming obvious to the city fathers that Exeter’s water supply was no longer fit for purpose. They contracted James Golsworthy, who ran the water engine that pumped water to the cistern behind the Guildhall, to improve the supply from the source in St Sidwell’s. He improved the pipes in the underground passages and trenches, and rebuilt the source at the welll. The flow was improved but it was still not enough and it was the building of the Pynes works above Cowley Bridge that solved the city’s lack of water for the citizens.

Despite the improved water supply to the conduit, the Improvement Commission approved the removal of the old conduit in 1833, for the widening of South Street, and in November 1834 it was demolished. Interestingly, Golsworthy reported to the Improvement Commission in 1835 that the old conduit did not hold water well, as the stone from which the tanks were constructed were porous. In 1836, accounts for the Exeter Borough Fund were published and it was noted that the income from the ‘water pipes and materials from the old conduit’ was £200, while expenditure on the ‘conduit’–presumably the new one in Milk Street–was £250.

The Milk Street Conduit

When Golsworthy improved the flow of water from St Sidwell’s, he installed a new conduit in Milk Street, in early 1835, to replace the South Street Conduit. He also ran a pipe down Mary Arches Street, where he installed a public conduit in the wall of his own house, for the locals. This small conduit can still be seen today, and is the last in the city to survive.

The Milk Street conduit was opposite the side of Fowler’s Lower Market, in what became known as Conduit Square. It was a simple granite obelisk with two outlet pipes, supplied from a tank installed in the Lower Market, which accounts for its slim size, albeit of solid granite.

A letter in April 1858, published in the Western Times, called attention to the poor supply of water to the Milk Street conduit, which the writer warned would get worse as the new railway cutting at Lion’s Holt was damaging the source at Head Well. The railway rerouted the supply along iron pipes to Queen Street Station for distribution, and for the first time for perhaps 700 years, the underground passages permanently stopped supplying water. The Milk Street and Mary Arches conduits were attached to the new public pipes installed by the Exeter Water Company at Pynes in 1865, at a charge to the Council of £15 per year.

The 1874, Finance Committee expressed reservations after it was revealed that Mr Gardener, the City Surveyor, had expended £42 to trace a leak in the supply to the conduit. They were particularly annoyed, as much of Milk Street was torn up searching for the leak, and felt that the Surveyor should have consulted local knowledge before the work.

The Golsworthy conduit in Mary Arches Street was disconnected in 1890, and possibly that the Milk Street conduit in the same year. The obelisk was in the heart of destruction from the May 1942 blitz, and all around, the buildings were either demolished or burnt out. It sustained damage during the raid, but remained upright. The old conduit was finally removed after the war in preparation for rebuilding.

Sources: The British Newspaper Archive (Flying Post, Western Times, Express and Echo and the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette), Water in the City by Mark Stoyle, Alexander Jenkins History of the City of Exeter, and the staff at the Underground Passages, Exeter.

│ Top of Page │