Saturnalia or Bonfire Night

How 'Young Exeter' celebrated bonfire night in the 19th Century

Page added 13th October 2013

Back to historic events in Exeter

Ever since that fateful night in November 1605, when Guy Fawkes and his accomplices attempted to blow up Parliament with 36 barrels of gunpowder, the English people have commemorated the event by burning effigies of the conspirators, the Pope and whoever was not in favour at that time. Indeed the very first ‘bonfire night’ was only hours after the plot was foiled, when Londoners lit bonfires in relief that their King had been saved, encouraged by the authorities "always provided that 'this testemonye of joy be carefull done without any danger or disorder'" (1)

During the 19th Century, young people across the country took the opportunity to have a good time, along with a big dash of anarchy and criminality. In Exeter, Bonfire night, or Saturnalia, (purloined from the Roman festival in December) was preceded by a ripple of dread for shopkeepers, the Cathedral authorities and the City Council.

‘Young Exeter’ as they were referred to in the newspapers, risked life and limb lobbing fireworks around Cathedral Yard and firing a huge bonfire just in front of the Great West Window. In 1847, the Western Times reported that the proceedings were generally opened by rolling tar barrels down the street. Wood was brought into Cathedral Yard by cart to build the bonfire, away from the mature elm trees – sometimes the bonfire was built with the tacit approval of the authorities, other times the timber fuel was hidden around the city until the last moment. Most of the windows around Cathedral Yard were boarded up, to prevent the rabble from smashing them.

At around nine at night, a huge effigy would enter Broadgate from the High Street, preceded by torch bearers and a guard of honour carrying staves and bludgeons, before being paraded around Cathedral Yard, occasionally stopping to acknowledge the crowd hanging from the upper windows of the buildings. The effigy would then be carried across the green towards the awaiting bonfire. Just before the great pile of timber, revellers would rush forward to light his neckcloth – the effigy, whether he be the Pope, Guy Fawkes, Bishop Phillpotts or some other unpopular cleric or politician, would then be placed on the pile of wood as the faggots at the base were set on fire.

Suddenly, the Cathedral and surrounding buildings were illuminated by a burst of bright flame and huge volumes of smoke would rise into the night sky, followed by a stream of sparks, threatening the timber framed houses around the close. So fierce was the heat that the authorities were afraid of damage to the West Front – year after year they would encourage the building of the bonfire away from the fragile West Front, but the local boys would take no notice.

Hideous Injury

The celebrations continued into the night with hand-rockets, roman candles and Bengal lights being set off with little regard to safety. Revellers hair and clothes caught fire, or they were hit by flying rockets, taking out eyes and smashing into bodies.

The Devon and Exeter Hospital, and the Infirmary were plagued with treating the many injuries caused by the fireworks – in 1865, ten were treated, four with serious burns, and one lad lost an eye – and this was a moderate year.

Fred Sparks, brother of Dr William Spark (who was a pupil of Samuel Sebastian Wesley) remembered the danger of bonfire night in the 1840s – see Memories of Saturnalia His description, more than the newspapers, gives a vivid picture of ‘Young Exeter’ paying a painful price for their celebration.

The Bishop objects

By the early 1850s, the Cathedral authorities tried to exclude the celebrations from the Close. In 1851, objection was made to the effigy of Bishop Phillpotts being burnt. The Cathedral authorities had no objection to Cardinal Wiseman or the Pope being burnt in effigy the year before. Phillpotts was a High Church Anglican, and therefore too closely allied with Tractarianism, thought by many of the local populace as being rather Popish. However, the local tradition was too strong for a mere bishop to stop, and the celebrations continued.

The close had come under the jurisdiction of the Local Board of Health in 1866, allowing the Mayor to take control. The next year, a large number of special constables were sworn in by the Mayor to control the night, and a notice was put out that the letting off of fireworks in the street was contrary to the law. ‘Young Exeter’ circumvented the restriction by rioting the night before. The Militia and the 20th Infantry were brought in from Plymouth to curb the riot.

Things did not get better in later years and in 1879, the Council boarded up the banks in Cathedral Yard to protect them, but the inevitable riot broke out. The police were attacked with stones and the mob tried to break into one of the banks. The Mayor, William Horton Ellis told the local militia to calm things down, but the rioting continued. He then entered the yard and read the Riot Act and ended with “Now, Colonel Drewe, do your duty" and the men loaded their weapons. The police under Captain Bent, drew their staves and waded in to the rioters at 1.50am – by 2.10 the crowd had dispersed. This was the last time a Mayor read the Riot Act in Exeter. One of the ringleaders, dressed as a monkey was given six weeks, and three others were also jailed.

The 1882 bonfire was one of the largest, but the Mayor decided to take a lower profile, and the night passed without any injuries. ‘Young Exeter’ issued their own proclamation for the celebration:

For be it known beloved each beloved son

Of Fair Exonia, who joins this glorious fun,

With frisky fireworks to commemorate

The thwarting of a crime, to seal the fate

Of Liberty; shall muster as of yore,

With lighted bonfire, and while cannon roar,

In my Cathedral Yard, let each one try

To preserve the peace and keep his powder dry.

In 1886 the Times reported that the night was celebrated in Torquay, Teignmouth and Dawlish with enthusiasm, but at Plymouth, Exeter and Dartmouth, the celebrations were more subdued. By 1888, the Times again reported, that at Exeter the celebration was larger than recent years. "Young Exeter" and the guys marched in procession with lighted torches, and accompanied by a band. In the roadway facing the west front of the Cathedral a huge bonfire had been erected, and on the arrival of the procession in the Cathedral-yard the pile was soon ablaze. There was also a display of fireworks."

The end of the party

The renewed enthusiasm was the death throe rather than rebirth of 'Young Exeter's' wild celebrations and a short column in the Western Times of 1893 remarked that this was the first year in which there was no bonfire in Cathedral Yard. Since then, Bonfire Night has continued to be celebrated in Exeter and around the country. Many households would have private bonfire in their back gardens during the latter half of the 20th Century, but it is becoming increasingly popular to attend an organised public display in the city. Modern sensibilities would no longer tolerate the anarchy, damage and danger of Saturnalia, but the events of the 5th November 1605 are still remembered by many across the nation.

Sources: (1) Biography of Guy Fawkes in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press. The Western Times, Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, The Times and the Flying Post, and www.bonfirenight.net

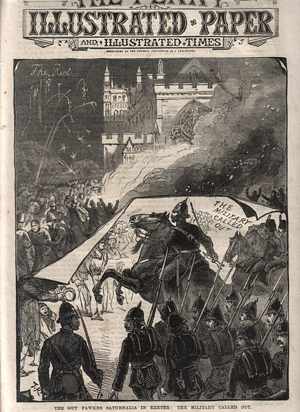

In 1879 the Mayor read the Riot Act as a warning before calling out the police and military.

In 1879 the Mayor read the Riot Act as a warning before calling out the police and military. The 1882 bonfire was particularly large.

The 1882 bonfire was particularly large.│ Top of Page │