Exeter Stories

Exeter folk and friends in their own words - 1890's to the 1990's │ << Previous story │ Next story >> │

Bombs at the Cathedral

by Miss Eunice Overend

For the first time since the raid, of nine nights before, we had dared to undress when we went to bed. It was an unlucky hope, for we were barely asleep when the sirens began to wail, and as we fumbled with the heavy blackout shutters in the dark there came the rattle of machine-gun fire over the roof. In a few moments we were dressed, for our clothes and tin hats were laid out by our beds, and we were on our jobs - Bebe downstairs to check the teams on duty (she was in charge of the hostel fireguard that night,) and myself to the roof. The city was faintly outlined below, while from above came the drone of engines. Suddenly across the darkness came a sparkle of lights, multiplying westward faster than one could count. Incendiaries! Tonight of all nights I must be at the Cathedral to help guard it again from the fires.

The bells shrilled as I pressed down the switch. Sleepy figures in slacks over pyjamas and tin hats over curlers appeared in the lighted corridors as I sped towards the door. The cycle was under the holly bush but locked, and the key upstairs! As I ran back for it, past the nervous warden without being seen, (for she thought the city no place for her charges when the alert had sounded,) I heard the crunch of the first bombs falling on the other side of the city.

The cycle sped down the hill to the city till the wind in my ears hid the sound of a falling bomb which exploded startlingly close. Then I proceeded with more caution, listening for that tell-tale whistle above the roar of engines and the bumping of the guns on the hill behind. A greenish glow came from York Road as I passed. Incendiaries were scattered along it and the front of one house was just catching. Should I stay and cope with it? No, my job was at the Cathedral. The next morning the whole block was gutted.

As I turned into the Close there came a whistle and in a flash I and my cycle were flat beside the static water tank. Whoosh! That was a close one! The Cloister Room with its lights seemed a haven of refuge. Signing the book I thought that at least they would know how many bodies to look for if we were hit. There I learned that the watchers had been ordered to come down and take cover, for what use can one be on a roof against high explosive? I joined the little group in the dark north transept where the group leader was checking names from a slip of papers by the glimmer of a shaded torch all safely down. Then the order came to scatter to the staircases in the thicknesses of the walls and I found myself with Zena in the short stairway leading to the Dog-whipper’s room. Zena sat on the stairs and I stood by the partly open door and watched the Cathedral grow slowly lighter inside as the fires outside spread. The planes droned slowly overhead then turned and dived, a crescendo of sound turning to a scream as the bombs shot to their mark. When the scream was especially loud and short we crouched on the stairs, clinging to the closed door, waiting for the crash. Often it did not come, till we lost count of the UXBs that had fallen.

The first explosion

At last the expected came. There was a whoosh that almost blew us up the stairs, a rumble of masonry and a tinkle of broken glass. The cautiously opened door revealed the Cathedral brighter than ever with beams of light from the broken windows streaming through the dust. From all sides came shouts – Everybody alright? Yes, we’re alright, - are you? No one was hurt, by the Grace of God.

The whine and crump of bombs continued and we sat in our staircase and swore at the Hun for thus daring to damage our beautiful city and Cathedral. The glow in the Cathedral got brighter and redder and smoke came swirling down the staircase. We decided that the north nave-aisle roof must be on fire and that we had better go round the outside and investigate before going up into it. We crossed the Cathedral in a lull, the broken glass crunching under our feet. The baize door from the south Transept was lying down the steps and we clambered over it to reach the Garth. At the gate we met a policeman who said that the north side of the cathedral was undamaged, but that Bobby’s shop was well and truly on fire, lighting up the sky and sending a stream of sparks overhead. That being so we took cover again for a short time while bits of plaster and tiles rained down around. Came another lull during which we drank a grateful cup of tea with the verger’s wife under the library stairs. While we drank there rose the wail of the All Clear.

Fire at Bobby's

In the Cathedral the watchers had emerged from their stairways and were climbing from the north Tower to remove from the roofs the splintered wood which might catch from the flying sparks. Half-way up we went through to the clerestory gallery to try and see where we had been hit, but as we emerged it was not the dim Cathedral that held our attention. Through the shattered window we saw the great fire at Bobby’s still burning redly [sic] while from all over the city came the lights, some streaming yellow some orange, of other fires. We had not realised the extent of the damage till then, and it occurred to us that we should ‘phone to reassure our nervous warden that we were all safe.

We made our way towards the south choir aisle where the Telephone was. As we reached the gate we saw the dim light of the sky where the roof should have been and an immense pile of rubble topped by a section of the leaded roof above the Telephone. Now we knew where we had been hit.

We crossed to the Deanery, still pursuing our object, and there learned that no telephones in the town were working. Most of the glass there was shattered, too, and the tattered blackouts were an invitation to the flying sparks from the South Street fires. We made a tour, pulling down the hanging paper and curtains. Somewhere on spring rods which stretched and hung limply, and we thought that late they would marvel at the strength of the blast! One could scarcely stand at the window facing the blazing paper-mill because of the intense heat. A Christmas paper-chain leaped from it and streamed upward from the wires of an already blazing telegraph pole. In a few seconds the flames caught it and it was whirled upwards, still burning, out of sight.

The gable of Kalendarhay adjoining the Deanery was already burning when we went round to investigate. Here we met the Dean with gum-boots and great-coat over his pyjamas, carrying a stirrup-pump. More fireguards appeared as we got to work. As I trained the jet on the burning gable from the iron staircase one of the masons took it from me and I went to pump for the second team. The heat coming over the remaining fifteen feet of the factory wall was so intense that the pumpers had to stand close beneath it for shelter, though it threatened to come crashing down at any moment.

Reinforcements arrive

Several ATS and members of the Pay Corps now arrived and one of them took over my pump for I was almost exhausted. Sparks were flying over the wall and I ran my hair and clothes under the tap for safety’s sake. Then I sat on a wall and passed buckets over and back while I got my breath again. One of the fireguards had got the promise of a branch hose from the NFS man whose pump was by the static tank in the Close, and they now appeared unrolling it. Close on their heels came Fred, another fireguard, saying that he and Peter had another branch and were trying to save the remains of the Choristers’ School on the other side of the Close, which had been damaged previously and now were in danger again from the sparks from the High Street fires. As I followed Fred across the green, stumbling over the twisted lead and glass from the Cathedral windows, I heard the roar as the trailer pump started up, a throbbing sound that did not cease for many days in the city.

At the end of the narrow alley we found Peter wrestling with the branch, for a jet has a powerful back kick. Between us we directed it on the naked roof timbers which were already alight. Then we saw that the fire from the High Street was spreading down Bedford Circus, as yet undamaged, which backed on the school. Even as we looked the flames jumped the gap from the chapel and caught a curtain hanging from a broken attic window. We tried to turn the jet on it, but the netting round the yard spilt the water and it would not reach, while the glow inside spread. The green double doors leading into the lane between the backs of the houses were locked but we forced them at last, and holding them against the strength of the wind which fanned the flames to an inferno, we did our best to drag the branch towards this new danger. It was a hopeless task; we slipped and slid in the mud of rubble and broken glass in the playground and the hose was already at its fullest extent.

While we played the jet uselessly into the lower windows of the burning building a messenger came up on a bicycle trying to reach the police station. The lane was blocked by flaming timbers a few yards further on, so we directed him through the yard to the Close. Then came two members of the Home Guard who said that one of the houses of the Circus not yet alight was their depot & was full of ammunition, but that they could not recognise it from the back. They stood looking on helplessly, so we gave them the branch and left them with Peter to do what they could, while we went back to the Deanery. There we found the gable, window and door had been extinguished by the jet from the hose, but that the rafters inside were smouldering and could not be reached.

Remembering the ladder leading to the Chapter House roof I collected two members of the Pay Corps and set out to fetch it. It was tied to the parapet at the top, so I cut it free and we took it over. In the heat of the moment we got to the wrong end uppermost against the Deanery wall, but soon jets of water were being directed on the danger spot. Below we slid and in a row of early peas fetching water and pumping in turn. The water pressure had dropped and buckets now took almost ten minutes to fill at the tap. Things were getting desperate when, almost by chance, I found a big lead rainwater tank on the wall by the Deanery door. The key for the tap was luckily on the bracket, and in a few minutes the pumps were working at full pressure again. The immediate danger passed, cups of tea were produced from the Deanery. As I drank I noticed a beautiful wine-coloured aubrietia on the rockery by the door. When I looked for it again later I found it was a common blue one. The sky was still quite black, but the glow from the surrounding fires still made it almost as bright as day.

The fireguards dispersed, for there were still many jobs to be done. Zena and I remained watching the drying gable, to give the alarm should it burst into flames again from the intense radiated heat. We looked through a big hole which had appeared in the garden wall over the sea of fire which had once been South Street. As far as one could see the gutted buildings glowed red, with here and there a still flaming beam, while a twisted lamp-post marked the shimmering haze where the pavement had been.

The worst is over

We sat down, wet and shivering, now the climax was past, behind the tool-shed and smoked a cigarette while guarding our gable. “Firewatchers” we felt, indeed, for we seemed to watch the whole city burn, and were able to do nothing. A blackbird sang loudly in the bushes, mistaking the firey [sic] light for the glow of dawn.

When the sky at last turned grey we decided that it was now safe to leave the gable and to return to our hostel to report. We set out through the city on foot, stepping over an endless network of hoses, our cathedral arm-bands getting us by all diversions, except those due to UXBs. By a roundabout way we reached Hoopern Fields and there fell in with another party of students from the second hostel who had come out since the raid as stretcher-bearers, and were now returning. They were called on at the Fire Station for a man with a broken leg, but had no stretcher left, so Zena set out across the city to call an ambulance.

When I reached Lopes, Bebe and I fell into each other’s arms, for we had each feared for the other’s safety. Their fears had been the worst, for at the height of the raid they had seen the spire of St Mary Major lit by fire and surrounded by smoke, but no sign of the cathedral’s Towers.

Lopes was now a rest centre, and the first problem was to boil water for drinking.

A brick cooker had been built previously, but no hole had been left into which to put the fuel. A little judicious stoking and it was soon blazing.

After breakfast, Bebe and I went down to the Cathedral again to see what could be done. Smoke was still rising from many parts of the city and firemen on their Towers were doing their best to save the small part of the High Street remaining, which was burning at both ends. We set about salvaging the old coloured glass which had been blown from the windows, some to the other side of the green, by the force of the explosion. Our biggest problem was to guard it from sightseers who trampled it into the grass and souveneer [sic] hunters who made off with what they could carry. In desperation I ordered a stranger away from the building, till I was told by and icy W.V.S. member that he was the Regional Commissioner! The best remark was made by one of the passers-by who was overheard saying to her companion that she supposed the Cathedral windows had been broken by the heat of the fires in South Street, - she should have been there!

Exeter Cathedral Library and Archive © 2013

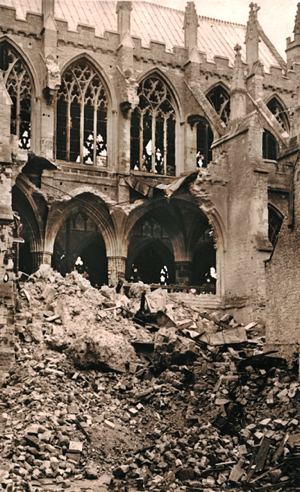

Blast damage in the nave.

Blast damage in the nave. The resulting damage from the high explosive bomb on St James' Chapel.

The resulting damage from the high explosive bomb on St James' Chapel.

Re-published by permission of Exeter Cathedral Library and Archives

[Exeter Cathedral Archives ED 119]

│ Top of Page │