Northernhay House, Northernhay Park

Page updated 17th December 2017

While researching the Exeter War Memorial in Northernhay Park, I came across a reference to it being partially placed on the site of Northernhay House. I had not previously heard of the house, so this page is the result of my research to find out more.

While researching the Exeter War Memorial in Northernhay Park, I came across a reference to it being partially placed on the site of Northernhay House. I had not previously heard of the house, so this page is the result of my research to find out more.

When researching houses that no longer exist, and where there is little archeological evidence, and few decent illustrations, the historian is left with consulting accounts of the people who lived there–and Northernhay House offers us two Mayors, three wine merchants, a Member of Parliament, a brewer, a dentist, a doctor and two schools.

Situated in Northernhay Park, the house faced the prison on the opposite side of the Longbrook Valley, with its rear built against the city wall. Nowadays the prison cannot be seen due to the mass of trees and shrubs on the fringes of the park, and the new flats lining New North Road.

The 1723 Sutton Nichols map of the city shows a park empty of buildings. It is little known that the strip of land between the city wall and the present path through the park from Queen Street consisted of a series of private gardens, and it is on some of these gardens that Northernhay House was built.

A new house in the park

Mr Hicks, a builder advertised the newly completed and furnished house in Northernhay, in the Sherborne Mercury in July 1789. He must have seen an opportunity to purchase some of the gardens and build a house for a gentleman, outside the clamour of the city, with extensive views across Northernhay Park, and the Longbrook Valley, towards the high woods of Duryard. The house stood in a large walled garden, with a coach house and stabling for two horses. The house contained two parlours, a kitchen, pantry, servants’ hall, six bedrooms, laundry room, cellar and the all important brew house, as water was not safe to drink.

It was thirty years later, in 1811, that the remainder of the 99 year lease was for sale, after the death of the then tenant, Captain Bailey. Those wanting to view the house had to apply to Mr. Hicks. By November 1813, the Rev. Edward Back was advertising for four pupils at 100 guineas per year, to learn Latin and Greek, at the house. Back had been a teacher at the Exeter Free Grammar School in 1801 and was the curate of St David’s Church. There was an advert to sell the house, in July 1816, when it transpired that the Reverend had vacated the house and migrated to Nova Scotia.

The burglary

The first indication of another change of tenant at the house was in October 1827.

"A daring robbery was affected between 3 and 4 o'clock Sunday morning, in the house of Mr Groves, dentist, Northernhay, Exeter. The party, after scaling the outer wall, got in at the parlour window, and having lighted two candles that had been burning the preceding night, broke open a secretaire, from which they took, in bank notes and cash, between fifty and sixty pounds. They were proceeding to the other parts of the house, but accidentally coming in contact with a hat-horse, threw it down, and by this means awoke the family upon which they decamped." Salisbury and Winchester Journal 29 October 1827

Two envelopes of money were in the secretaire–one containing £40 for a trip to Ireland, which Anthony Groves was to use to enroll as an external student of theology at Trinity College, Dublin, was taken. The second envelope contained £16, which he had kept as a collector of taxes.

If the robber had been caught, he would have been hanged—the law did not reduce the penalty from death, until 1830. Eighteen months later, in March 1829, a short article appeared in the Flying Post, about a case at the Guildhall. A tailor, Thomas Salter was charged with theft from the house of the dentist Mr Groves. He was brought for examination in front of the bench, who were shocked to see his emaciated appearance "Meagre were his looks... Sharp misery had worn him to the bones." Anthony Groves, driven by his faith, "... declared he would not proceed against a fellow creature in such distress, and instantly tendered him pecuniary aid..."

Salter had hit hard times, when officers were sent to his house to arrest him. They were appalled to find his wife and children in equal distress, without a stick of furnishing in any room. With Groves declining to prosecute, Salter was ordered to be relieved and removed to Bradninch, his home parish.

A month after the case at the Guildhall, it was announced that Groves was to leave Exeter to be a missionary in Persia, giving up a dental practice worth £1,000 per year. He became a renowned missionary and traveller through the Middle East, India and Russia, and was influential in the foundation of the Pymouth Brethren. John Kitto, a foundling from Plymouth whom Groves employed as a dental assistant from 1824, went on to publish Kitto's Bible and become an influential theological writer and author of many travel articles.

Anthony Groves vacated Northernhay House for Bedford Circus, in 1828, the year before the Guildhall case and the panic at the baptism. Mr and Mrs Hake’s Preparatory School (infant and boarding) moved into the house from its previous premises. The school remained until 1834.

A brief hurricane

By 1836 the Mayor, William John Players Wilkinson, and a wine merchant, was in residence. It was during his time living at the house, that the City Council endlessly debated the poor state of the park, and commissioned plans for improvement. Eventually thirteen pine elms were cut down, to the anger of some. A ‘hurricane’ across the county in December 1836 felled several more trees, while the house narrowly escaped damage.

Wilkinson wrote to the Western Times in November 1846, objecting to the gates of the park being closed and locked at 9pm. Although he and his family had keys, friends who were invited to visit could not pass through the gates when closed. During this time, Wilkinson purchased shares, at £25 each, in the extension of the atmospheric railway extension to Ilfracombe, via Barnstaple. A conventional railway eventually reached Barnstaple, and it is likely he lost his money in the caper. Wilkinson died at his home in East Wonford in January 1849.

There was a second residence attached to the main house, that may account why there were others mentioned in the newspapers who resided there while Wilkinson was in residence. In 1842, William Henry Thompson gave his address as Northernhay House at the City of Exeter court as an insolvent debtor. It was not until October 1850 that Thompson’s insolvency was settled when he had to pay out 1s 11d in the pound.

Upon Wilkinson's death, the house was put up for let, now with a dining, breakfast and drawing rooms, a study, servants’ quarters, a water closet on each floor, running water and the coach house and stables.

By 1852 Major Godfrey had settled in retirement in the house. However, it was the exploits of his nephew that are of note–Captain Godfrey, commanding the “Statesman” carrying migrants to a new life ‘down under’. He broke the record for a passage to Australia, with 76 days and 10 hours from Plymouth to Melbourne. He had broken his own record of 77 days, the previous year, for the same passage.

Links with the City Brewery

The next prominent citizen to live in the house, from 1857, was John Evony Norman, who was a director of the City Brewery in Commercial Road. The company became Norman and Pring in 1865. He was soon an influential man in the city, both politically, and socially. Norman was the first man to register a car in Exeter with the number FJ1.

Demolish it

The Council had plans to purchase the house in 1859, with the intention to demolish it, for in the opinion of Councillor Wilcocks:

"... (it) should be removed to afford the inhabitants a better view of the surrounding country to compensate them for the loss of so large a portion of Northernhay; but added that it did not appear at present either of these promises would be fulfilled." Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 19 February 1859

However, the house did lose some garden and outbuildings for incorporation into Northernhay Park. Building materials from the outbuildings were auctioned in November 1859. This led to some skullduggery involving the Mayor, Councillor Tanner. There was a Banqueting Room, that belonged to the council, in the house, for auction. It was quietly withdrawn from the sale and sold to Mr Muir, a friend of the contractor for £15, who then passed it on to the Mayor for the same sum, way below its true value. While all this was going on, the engineer, Mr Taylor, of the Yeovil Extension Railway that was coming into the city through the Longbrook Valley below the park lived in the house.

Another wine merchant

So far we have had a wine merchant and a brewery owner living in the house. In 1867, Benjamin Faville Carr, another wine merchant moved in. When he died in 1870, his son joined forces with Mr H Quick to form Carr and Quick, who some will remember as a prominent Exeter business, occupying a shop on the corner of Queen and Paul Street.

Even though Northernhay House was a private dwelling, its position within the park, and size made it a popular place for special occasions. The Exhibition of Bees and Honey was held there in 1877 and 1878. It was promoted by the Devon and Exeter Bee Keepers’ Association, with the purpose of encouraging “cottagers and labouring classes” to improve their bee keeping.

Moving on to 1879, and the widow of Mr Richard Somers-Gard, who lived in Rougemont House, purchased Northernhay House. The house was leased to William Dymond, a not altogether successful wine merchant, who became insolvent in 1883 for £19,000. He started another business in 1884 with £150 capital, and this too, folded, within three years, with debts of £610, and assets of £12. Mrs Somers-Gard evicted Dymond in 1884 for non payment of rent.

The last tenant

The property was for rent again from Midsummer 1898. It was described as having a “Dining-room, double drawing-room, study, large room 30x18, suitable for billiard room, kitchen and usual offices, seven bedrooms, dressing room, bath room, stable, coach house, lawn and large walled kitchen garden.”

It was quickly rented by the surgeon, Edward Domville MRCS, who would become the last occupier. He first appeared in Exeter attempting to form a “Brotherhood of St Lukes”, at the Devon and Exeter Hospital in 1870. Its membership was aimed at Catholic Anglican medical students and doctors, who would use their faith to direct their care–it was controversial, and met some considerable opposition. Domville became involved in Exeter society, as a member of many committees related to public health and welfare, culminating in becoming Mayor of the City in 1893. His only son, David died, aged 28, in 1908.

Bought by the council

The owner of Northernhay House, Mrs Somers-Gard died in 1889, and the Rougemont Estate which included properties in Castle Street was sold to Miss Phoebe Outhwaite, who died in 1899 leaving the estate to her sister Margaret Outhwaite. She died in 1911 when the Rougemont Estate came up for sale. In co-operation with the City Council, Edward Domville purchased Northernhay House, for £2,400, in February 1912, with the intention of selling the house to the Council, and being allowed to remain as a tenant for as long as he required. The Council had the long term aim of demolishing the house once vacated by Dr Domville. The good doctor remained living at the house until Lady-day (25 March) 1913, when he moved to Bristol. Although the Council immediately made plans to demolish the house, and auction the building materials, nothing was done.

The threat of war was looming in Europe, and the Exeter Voluntary Aid Organisation ran a 'Field Day' in May 1913, to practice what would be done if a large number of casualties had to be treated. The public were invited to see what the VAO did—one of the Temporary Hospitals in Exeter was Northernhay House.

However, the use of the house as a Temporary Hospital never happened. In February 1914. It was described as being “… in a most dilapidated state”, and it was demolished. The site was landscaped and added to Northernhay Park. The Exeter War Memorial partially covers the site of Northernhay House. If you visit the War Memorial now, there is absolutely no clue that there was a large, seven bed roomed house in the park.

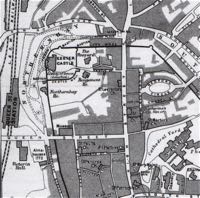

There are no illustrations of Northernhay House in existence, and no architectural descriptions. The only evidence of the size and shape of the house are several maps, although only one, published by Longmans, Green and Co of 1886 actually names it.

Sources: Sherborne Mercury, Exeter Flying Post, Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, Morning Chronicle, Western Times, Royal Cornwall Gazette, the Salisbury and Winchester Journal and the North Devon Journal. Various maps including the 1886 Longmans, 1723 Sutton Nicholls, 1765 Donne and the 1805 Britton.

│ Top of Page │