Exeter in the Great War

Latest update 5th May 2017

Back to historic events in Exeter

1915

1916

1917

1918

Roll of

Honour -

Great War

1914 - A Minor Assassination

Like many other places in England, Exeter had enjoyed a pleasant, hot summer in 1914. That little business of the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Serbia, on 28 June was worrying to a few, but it did not mean much to many. However, as diplomacy failed across the continent, the states of Europe formed up against each other in their alliances, and on 28 July Austro-Hungary declared war on Serbia. On 1 August, Germany declared war on Russia and, on 4 August, Germany declared war on Great Britain. France, Russia and Belgium also joined in, to what would become the Great War, and misappropriately 'the war to end wars'.

War is Declared

For those who wanted to know the latest state of negotiations to prevent war, the only place to be was outside the Western Times Office at 226 High Street. On the evening of the 4 August, a crowd gathered outside the newspaper office, waiting for the latest news to be posted in the window. When Germany declared war on Britain, the Western Times reported it thus:

"A scene of tremendous enthusiasm was witnessed in Exeter last night when the intimation came that war between Germany and England was an actual fact. A crowd of many hundreds had been waiting in the High-street outside the “Western Times” Offices, reading with avidity every item of news as it was posted in the windows, and when at midnight the first announcement was made that Germany had declared war on England, the throng was moved to an impressive outburst. A tremendous cheer was raised, and then all heads were bared while by general impulse the National Anthem was sung. This was followed by hand shaking."

Banks across the city posted notices saying they were closed until the next day, in accordance with the Royal Order. The staff of many businesses were depleted when they joined their units in the Reservists and Territorials. Notices were posted in the local papers, announcing the postponement of many marriages, as young men joined their units. The city prepared for war and guards were posted at the railway tunnels under Mount Dinham and Mount Pleasant Road and also at the Cowley Bridge. The Regulation of Forces Act of 1871, was invoked and the railways were brought under Government control. The Act affected local businesses who were requested:

'To provide the transport for the Territorials on the march to Exeter a number of farm waggons were requisitioned, and the steam lorries of a city brewery and another firm were also taken by the military'.

Of the first four official British casualties of the Great War, one was leading Stoker Henry Copland of Topsham, who was killed on the 6 August, when H.M.S. "Amphion" investigated a German naval vessel laying mines in the Thames Estuary. Amphion hit a mine and sank.

On Saturday 8 August 1914, the weekly Flying Post announced to the citizens of Exeter that war was declared with large, bold headlines, although, by then, there were few who did not already know. The issue had a prominent advert for young men to join up.

The Flying Post wrote the day after war was declared:

"Scenes of enthusiasm which were witnessed on Tuesday, when the Devon and Cornwall Brigade of Territorials marched from their camp at Woodbury into Exeter continued until late evening. The 4th Devons, in which citizens were naturally most interested, were the last to arrive about nine in the night, and as they passed through the streets on the way to St Davids Station they were cheered by the thousands of citizens. There was a remarkable scene at St David's a great crowd cheering the men, the King, and the French nation, finally singing the National Anthem and 'Rule Britannia'. Another burst of enthusiasm in the High-street greeted the news of the declaration of war against Germany'."

The military also required equipment and stores

including horses for riding and draught purposes. All owners of horses

had to report with their animals to gathering points through the

country. In Exeter a field near Higher Barracks was used, where remount

officers and local vets inspected them, and made immediate payment for

suitable animals.

Many made gestures to help the war effort, including the Dean of

Exeter, who vacated the Deanery at the request of the authorities for

the use of

the many war nurses and Red Cross personnel that were being recruited,

and four lay vicars were enlisted. The Bishop of Exeter donated a

days collection of the Fabric Maintenance Fund to the Archbishop and

Mayor of the Belgium town of Malines (Mechelin) after it sustained

heavy damage during the early offences.

Prices of some commodities immediately went up, as shortages were expected - "potatoes have advanced 3d per stone. Bread and flour will be increased on Monday'. The postal service was also hit when the number of deliveries per day was reduced from 5 to 3.

There were fears that the players and management of Exeter City Football Club may have been interned in South America at the outbreak of war. The club had played a series of matches in Argentina and Brazil through July. On the 11 August, news arrived that they had landed at Liverpool, to the relief of many.

The first months

Exeter became the first provincial town to take refugees, when 120 Belgians arrived. By the end of October over 800 had settled. The city also received 20 Germans who were arrested in Torquay, and brought to Exeter for internment.

The Billeting Officer was charged with the task of finding quarters for the soldiers who could not be accommodated in Higher and Topsham Barracks. His representative would call on local households, looking for rooms. For some families, this was a chance to make a little extra income in hard times, as an allowance of 7 shillings was paid per man. This arrangement only lasted a few weeks, for after training, the men were sent to France.

The West of England Eye Hospital was mobilised within 24 hours of receiving orders, on the 4th October 1914. It would become VA Hospital No 1, the first of six military hospitals in the city. The first men from the fighting at the front were disembarked from ships at Southampton and brought by train to Queen Street Station. In the same month, a children's home was also requisitioned for treating the sick from the local garrisons. Within 12 hours the children had been moved out and sixty beds were ready to receive the troops.

On 22nd October, the first Canadian troops, a Motor Transport detachment of motorised machine-guns and a supply column passed up Alphington Street and Cowick Street, watched by a large crowd. They camped at Fairfield in Okehampton Road for the night, before driving over the Exe Bridge and up Fore Street, and proceeding to their camp at Salisbury Plain. The main body of Canadian troops, numbering some 32,000, along with 7,679 horses, passed through Exeter on 92 special trains from Plymouth to Salisbury Plain. One of the officers, Major John McCrae would compose the phrase "In Flanders Fields the poppies blow, Between the crosses, row on row." which would prompt the use of the poppy as a symbol of remembrance.

Christmas 1914

Life continued as it had before the war, and Christmas was to be celebrated. Mother Goose was the pantomime at the Theatre Royal that year, and even the Palladium Cinema in Paris Street was showing a film of a pantomime. The Times ran a daily Fund for the Sick and Wounded, with a list of donors, and on the 17th December, T E Vine, Headmaster of Mount Radford School donated £7 7s. A week later and W R Mallett Ltd, of Exwick Mill donated £25, and the staff and boys of Exeter School contributed £10 18s 11d.

The war was to become much closer when the Flying Post published the roll of honour for the first five months of conflict, listing the wounded, missing and 34 killed in action and one death from wounds.

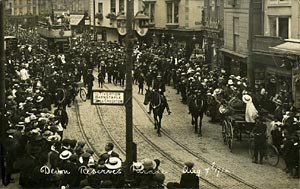

August 7th 1914 - the Devon Reserves parade past London Inn Square and

Eastgate.

August 7th 1914 - the Devon Reserves parade past London Inn Square and

Eastgate.

New recruits in Church Road, St Thomas marching away from the County Ground, where they

enlisted.

New recruits in Church Road, St Thomas marching away from the County Ground, where they

enlisted.

The 7th Devonshires showing off their bicycles.

The 7th Devonshires showing off their bicycles.

Army motorcyclists and requisitioned vans on parade. Standfield and White have donated their van, right.

Army motorcyclists and requisitioned vans on parade. Standfield and White have donated their van, right. Canadian troops at Fairfield, St Thomas.

Canadian troops at Fairfield, St Thomas.

VA stood for

Voluntary Aid

Association.

The Red Cross derived organisation that supplemented the army medical service of the Territorial

Force.

Some of the VA Hospitals in Exeter:

VA 1 - West of England Eye Hospital

VA 2 - The Modern School (Bishop Blackall)

VA 3 - The City Hospital, Heavitree

VA 4 - Topsham Barracks

VA 5 - The College Hostel (Bradninch House)

VA 6 - Bishop's Palace

(from 1917)

VA 7 - Streatham Hall Temporary Hospital (from 1917)

VA 8 - Southernhay various houses

│ Top of Page │

1915 - The first casualties

On New Years Day, 1915, HMS Formidable, an elderly, pre-Dreadnaught Battleship was torpedoed off Start Point - she was the first major loss for the British Navy during the war. Out of a complement of 750 crew, 199 men were saved. The survivors were cast afloat on a rough sea out of the site of land. Several ships passed the survivors lifeboats without noticing them, before Miss Gwen Harding, walking with her mother at Lyme Regis, saw one of the boats and raised the alarm. Locals took in the shipwrecked men, while the dead were laid out in the entrance to the cinema. The Mayor of Lyme telephoned the Exeter Mayoress, Mrs J G Owen, for help. Clothing and other necessities were despatched to Lyme to aid the survivors. Another boat from the battleship was picked up 15 miles off Berry Head.

In the same week that the Formidable was sunk, another 43 Belgian refugees arrived in Exeter via Folkestone, while the Mayoress' Fund benefited from the money raised by putting on display two sharks in Sidwell Street, that had been caught at Exmouth. The Mayoress was a formidable fund raiser and organiser, having raised £400 since the outbreak of war, to purchase bags of food for the soldiers passing through Exeter by rail. In February 1915 she, and four other ladies were supplying a bag with a large sandwich, two pieces of cake, orange or banana and a pack of cigarettes to every soldier from the platform of Exeter's stations. They had supplied food to 12 to 13,000 soldiers between September and January.

Also at the start of the year, Literature for the Front collected 989 parcels of books and periodicals at the Guildhall. They sent 161 boxes, or 13,500 publications for the men in the trenches. Each box also contained needles and thread, bootlaces, embrocation, cards, Vaseline, foot powder, biscuits, cigarettes, socks and mittens. In February, a 12ft by 4ft red cross flag was given to VA Hospital No 1 by nursing staff who had raised the money to purchase it. Miss Georgina Buller raised the flag for the first time.

The sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915 with the loss of a 1,000 lives was a traumatic shock to many across the country. In Exeter, and elsewhere, German shops were attacked and damaged by enraged citizens.

On June 9th the Flying Post contained this advert for men to join up:

'These boys didn't shirk, they want help. Listen for a moment - can't you here (sic) them calling to you? BE A MAN. There's a king's uniform waiting for you, go and put it on now'

Mr J Westcott of Poltimore was commended as his six sons had joined up, and taken the King's colours. As he and his wife were bidding their sixth, and youngest fair well as he left for the front, news arrived that two other sons had been wounded in action. Tremlett Bros Ltd contributed £262 10s to the Times Sick and Wounded fund in the June, and Maynard's collected £8 8s from a small sale for the Transport of the Wounded Fund.

In August 1915, the Committee of the Exeter Diocesan Training College (St Lukes) temporarily closed the college. At the outbreak of war three staff and 100 students were mobilized, and in January 1915, a large part of the buildings were given over to the Army Pay Department, making it impossible to accommodate the full complement of students required by the Board of Education. In October the Flying Post wrote that Professor Jacob had been running French classes for soldiers before they left for France. Three hundred had taken advantage of the lessons, which were held on the premises of C J Ross at 227 High Street.

The Royal Visit

For Exeter, the big event of the year was the visit of King George V and Queen Mary to two VA hospitals in the city. There had been established five VA military hospitals in Exeter to care for the wounded. Other places in Devon also had VA hospitals including Plymouth, and many large houses in country areas were requisitioned as convalescent homes.

On 9th September 1915, the Royal train steamed into St David's at 11.03am to be greeted by the Mayor J G Owen, proprietor of the Express and Echo, along with the Lord-Lieutenant of Devon and other dignitaries.

The Royal party was conveyed in a fleet of five motor cars, belonging to prominent citizens, to the West of England Eye Infirmary, or VA Hospital No 1. This was the first time a visiting monarch had driven in a motor car in Exeter. The King and Queen visited every ward, spending 45 minutes chatting to recuperating soldiers from the front. They then inspected 170 soldiers from other local hospitals in the grounds.

The King addressed the men and said "The Queen and myself are very pleased to have been able to visit you. I am very proud of the splendid manner in which you have fought and done your duty in the Dardanelles or Flanders". The men gave a 'hearty cheer' and as the King and Queen left, they sang the National Anthem.

The cavalcade then proceeded along Magdalen Road, Denmark Road, Barnfield Road and Bedford Circus, cheered on by the crowd of locals, to VA Hospital No 5, which was the Castle Street Hostel, now known as Bradninch House. The King inspected all the wards, containing 150 patients, then went into the garden at the rear to inspect a further 300 convalescing soldiers. Staff from VA Hospital No 2 (now the Bishop Blackall building) and VA Hospital No 4, Topsham Barracks, were presented to their Majesties.

Private G Bidgood was presented with a D.C.M. for single handedly, holding a trench against the Turkish enemy in the Dardanelles campaign. Of course, the proceedings closed with a rendition of God Save the King!

The Royal Party returned to St David's and their train departed at 12.50pm. After the visit, all the wounded soldiers who could be moved, and the soldiers visiting from other hospitals across Devon were taken to the Victoria Hall for lunch. Some 200 local motor cars were used as transport.

Other Events

During 1915, another 3,000 Belgium evacuees arrived in total, in the city, and were accommodated across the community from Exwick to Pinhoe. Refugees would arrive in batches of 200 to 300 by train at Queen Street to be taken by tram to a local hostel. They would then be dispersed across Exeter and Devon. Pinhoe raised £382, and donated toys, bedding and other household items, over the four years for the rent and furnishings of three houses for refugees.

The Exeter branch of the Vegetable Products Committee sent 30 tons of fruit and vegetables to the Fleet in the November, and for the first time, uniformed post women were employed, initially to deal with the Christmas rush in December 1915.

The Captured Guns

Two German field guns, captured by Bullers Own, the 8th and 9th Devonshires at the Battle of Loos, during September and October 1915, were brought back to Exeter. They were hauled, under escort, from Topsham Barracks to the Rougemont Hotel and presented to the Mayor. Then they were taken on a tour of the streets, around the West Quarter and down to the Exe Bridge, so that Union Flag waving Exonians could cheer their capture, before they were put on display in Northernhay Park.

Figures for the

VA hospital system

in September 1915

Beds in Exeter hospitals 570

Occupied 520

Hospitals in Exeter group

Devon VA hospitals 20

Devon convalescent homes 16

Maximum number of beds 1.364

Occupied 1,085

Patients admitted to date

Exeter 3,343

Devon 1,894

The

King and Queen at the VA Hospital No 5 (Bradninch House) talking to Driver Pyne. The medic is Dr Dyball who was in charge of VA 5.

The photo was taken by Mary Hare.

The

King and Queen at the VA Hospital No 5 (Bradninch House) talking to Driver Pyne. The medic is Dr Dyball who was in charge of VA 5.

The photo was taken by Mary Hare. The

Queen and Dr Henry Davey at VA

Hospital No 5.

The

Queen and Dr Henry Davey at VA

Hospital No 5. The captured German guns at Northernhay Park.

The captured German guns at Northernhay Park.

An Exeter post woman in her uniform.

An Exeter post woman in her uniform.

Men recruited from Cardiff, in Exeter as part of Kitcheners Army.

Men recruited from Cardiff, in Exeter as part of Kitcheners Army.

│ Top of Page │

1916 - Restrictions bite and casualties mount

MOURNING - Black costumer, Black jackets, Black shirts for immediate wear. A large stock to select from - Gibsons, 198 High Street, Exeter

The above advert appeared in the Flying Post during January 1916, a year in which many Exonians would wear black.

After 18 months of war, Exeter, along with other towns and cities in the country was having to apply restrictions, both to preserve resources, and to protect the citizens. The price of the 4lb. loaf was raised to 8½d in Exeter. In February 1916, an order went out that the streets were to be darkened because of the threat from Zeppelins.

This new weapon had terrorised the east coast of England, and rumour and speculation had forced the authorities to act. At the same time, the Council were directed by the Government to print and distribute air raid precaution leaflets, at a cost of £12 3 shillings. However, letters were published in a local newspaper that doubted whether such a raid was possible so far west. Little did Exonians know that 25 years later, they would have to endure a real blackout, to protect them from a very real aerial bombardment.

To add to the general disruption, the Corporation Trams stopped running an hour earlier each day from March, to conserve coal at the electricity station. The lack of coal hit the local schools, and Newtown Girls' School closed half an hour earlier in the afternoon, to reduce the use of both coal and gas. The school also put on a concert in December to raise money for prisoners of war, and the children brought oranges, apples and cigarettes to the school, to be distributed amongst the wounded in Exeter's VA Hospitals.

Also in February the Exeter Police Force introduced its first police dog.

The Exeter police, the Chief tells us, have an Airedale dog—a dog, we presume, which has a "bite" as well as a bark.

Western Times - Thursday 17 February 1916

In February, the Royal Society for Arts introduced an English for Refugees examination to encourage the many, mostly Belgian, refugees to learn the language. After spending four months in hospital in Exeter, recovering from a smashed jaw, Private William Young who had been awarded the VC for his courage in action, returned during April to Preston, his home town.

The 31 May 1916 saw the biggest sea battle of the Great War when the British fleet scored a pyrrhic victory over the German fleet at the Battle of Jutland. Twenty-six men from Exeter died on that day in the battle.

The

Battle of Jutland

BALSON, Ordinary Seaman, Aaron James, Age

18. Bartholomew St

BEALEY, Cook's Mate, Francis Harold, Holland Rd.,

St. Thomas

BENNETT, Private, COURTNEY WILLIAM, Age 21. Albert St

BISHOP,

Stoker 1st Class, WILLIAM FRANK, Age 22. Park St

CHURCHWARD, Leading

Stoker, Christopher Marks, Age 25. West Grove

CLEAVE, Petty Officer

Stoker, Benjamin James, Age 39. Parents from Exeter

COLLETT,

Private, John Henry, Age 32. Bishop's Buildings

DADD, Able Seaman,

George William, Age 31. Native of Exeter

DORMAN, Private, Alfred

George, Age 26. Goldsmith St., Heavitree

EVANS, Stoker 1st

Class, John, Age 21. North St

GATER, Stoker 1st Class, Frederick,

Age 21. Cowick St

GOSS, Artificer Electrical 4th Class, Herbert

George, Age 27. Roberts Rd., Larkbeare

KEMP, Ship's Cook, Frederick

George, Age 29. Clifton Rd

KNEEL, Clerk (Assistant) Jack Arthur

Charles, Howell Rd

KNIGHT, Leading Stoker, George Francis Edward,

Age 24. Roberts Rd

LEMON, Able Seaman, Herbert George, Age 20.

Trinity St

PEAKE, Stoker 2nd Class, George William, Age 25. Parents

in Exeter

PHARE, Leading Stoker, William, Age 24. Morgan Square,

Paris St

RAFFERTY, Private, John Henry, Age 27. Radford Rd

SANDHAM,

Private, Frederick James, Age 29. Elton Rd

SHAPCOTT, Boy 1st Class,

Reginald Stanley, Age 17. Native of Exeter

TAYLOR, Stoker 2nd Class,

William John, Age 23. Oxford St

TODD, Stoker 1st Class, Richard

Giles, Age 21. Native of Exeter

TUCKER, Leading Telegraphist,

Claude, Age 22. New North Rd

WILLEY, Ordinary Seaman, Frederick, Age

18. Wellington Rd

WILLIAMS, Private, Sidney Joseph, Age 25. Born at

Exeter

Just a month later, the country and the city reeled from the losses on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, on the 1st July.

Exeter Dead–First day of the Somme

ASH,

Private, J, Age 18. Improvement Place, St. Thomas

BAILEY, Private,

Frederick Henry, Age 21. Priory Rd

BRADFORD, Private, John Henry,

Age 20. Alphington

CARR, Drummer, W F J, Age 19. Parr St

COCKER,

Private, Robert, Age 25. South St

COOK, Private, G B, Topsham

COURT,

Private, Alfred Charles, Age 21. St. Edmund Square

COX, Lance

Corporal, Charles Edward, Age 25. Howell Rd

DEVILLE, Corporal, W H,

Age 25. Friar's Walk

EBDON, Corporal, Samuel Mark, Age 26.

Summerland St

ELSTON, Private, John, Age 41. Cowick St

FITZGERALD,

Private, John, Age 22. Summerland St

FOSTER, Lance Corporal, Thomas,

Age 28. Red Cow Village

GRANT, Private, H, Springfield Rd

HETTISH,

Private, F J, Bear St

NETHERCOTT, Private, Walter Jacob, Age 27.

Alpha St., Heavitree

PRINCE, Private, Sidney Francis, Age 22.

Springfield Rd

REED, Private, A J, Age 19. South Wonford, Heavitree

STABB,

Private, E, Age 26. Edmund St

THRESHER, Serjeant, A, Shrubbery

Place, Heavitree

WHITE, Captain, George, Age 29 Paris St

WILLIAMS,

Private, Marshal, Age 22. Clifton Rd

The 7th August was declared by the Mayoress as 'Forget Me Not Day' - a collection was made for Exeter's Hospitality Fund to provide food for the troops travelling to the front by train. Individuals also gave generously to care for the troops and the Flying Post printed "For the Wounded - Mr S Godfrey Walker of Northbrook Park, has given £1,000 to provide huts at No. 1 military hospital (the Eye Infirmary)."

The Ambulance Trailer

To ferry wounded soldiers from the front to the VA Hospitals, the Ambulance Service Corps was formed in 1915, although it did not get going until 1916. It consisted of private cars hauling a small trailer that could take two stretchers side by side to the designated hospital.

The Western Times reported on one of the first Trailby motor trailers to be delivered.

A valuable gift to the V.A.D. at Exeter is being made by the employees of the Western District of the L and S.W.R., through Mr Hoyle, the Superintendent for the district. They have purchased at a cost of £40 a Trailby motor trailer for use for serious cases. The trailer can be attached to an ordinary motor, and it has the advantage of being suitable for the conveyance of stretcher and the cases.

Western Times - Friday 04 February 1916

The Trailby motor trailer, was presented to Miss Georginana Buller. Further trailers were given to the service, with the AA, then based in Sidwell Street, donating three trailers in November 1916.

The Volunteer Ambulance members had to pass an examination as part of the Devon Volunteer Regiment, and the drivers were often the owner of the vehicle. Badly wounded troops would arrive at Queen Street Station, and be transferred to a trailer, while the car was loaded with walking wounded, and despatched to one of the five VA Hospitals in the city. One of the owner drivers was Bertram Percy Tucker, who worked for the Wilts and Dorset Bank in the High Street.

By December 1916, there were 60 county hospitals with 1,600 beds looking after wounded soldiers. On the 16th December, Miss Georgina Buller made a plea for donations for the hospitals to be sent to the VAD Office at 11, Southernhay. On the same day Lord William Gascoyne-Cecil was appointed the new Bishop of Exeter.

Two Bishops lose five sons

The new Bishop was to lose three sons in the war. Randle William Gascoyne Cecil was the eldest son. He was killed on 1 December 1917, aged 28, at the Battle of Cambrai, serving in the Royal Horse Artillery. Lieutenant Rupert Edward Gascoyne Cecil, Royal Horse Artillery was killed on 15 July 1915 at Ypres. He was the fourth son of the Bishop, and was just 20 when he died. John Arthur (Jack) was killed, aged 25, in August 1918. Jack was a Captain in the Royal Horse Artillery, and was awarded the Military Cross in 1918. The Bishop never recovered from the loss of three sons. He remained Bishop of Exeter until is death in 1936.

The Bishop of Crediton, the Right Rev Robert Edward Trefusis, also lost his two sons, Captain Arthur Owen Trefusis and Captain Haworth Walter Trefusis on the 7 July and 7 November 1916 respectively.

Citizens from every small street of the city made sacrifices, and Mrs Rawle, a widow, of 56 Hoopern Street was one, when it was announced in the Express and Echo, during November, that she had eight sons serving in the forces, three of whom were in France. One of her sons, Private Reginald Llewelyn Rawle, of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps appears on the roll of honour, having died on 17 February 1919, aged 31.

Charles E. Tudor Jones who was articled as a solicitor to Mr H. W Michelmore, was killed in action in January 1916. He was a Second-Lieutenant to the East Lancashire Regiment, attached to the Royal Flying Corps, as an observation officer. He and his pilot were shot down in aerial combat. He was buried with full military honours, and the German Flying Corps sent wreaths to his grave.

Entertainment

The Economy Exhibition was held at the Victoria Hall, from the 24 November, to educate the harassed housewife on how to cope with wartime deprivation. Miss Florence Petty, who was known across the country as the 'Pudding Lady', gave a lecture at 4.30 very day on the 'servant problem' and on 'housecraft'. She demonstrated how to prepare meat substitutes in front of the audience, which were then offered the cooked food free of charge. She also covered cerials and fats, the economical use of meat and fish, hygiene in the home and foods to eat to help the teeth. It was hoped that such events would help to conserve the nations resources, reduce imports and free up shipping for conveying men and munitions.

The war was temporarily forgotten in December when Dellers Cafe opened its doors for the first time. It was constructed over Lloyds Bank, a single storey building on the corner of Bedford and High Street. At last, the busy, servant less housewife, could indulge in a little luxury, and forget Miss Petty's lectures on meat substitutes!

The Theatre Royal continued its performances throughout the war, entertaining locals and the many visiting soldiers. West End stars would often appear at the 2pm 'Flying Matinee' performance, to return to London by train for their evening performance. They would then return to Exeter the next day for a repeat matinee. The annual pantomime at the theatre was Cinderella, the first time they had performed the story.

The manufacturers photo of the Trailby.

The manufacturers photo of the Trailby. Percy Bertram Tucker by his car

and Trailby Ambulance Trailer at Queen Street

Station. Photo Paul Tucker.

Percy Bertram Tucker by his car

and Trailby Ambulance Trailer at Queen Street

Station. Photo Paul Tucker. The Theatre Royal stayed open through

the war.

The Theatre Royal stayed open through

the war.

Ambrose Tucker

and his father growing

much needed food in an allotment

in St Leonards. Photo Paul Tucker.

Ambrose Tucker

and his father growing

much needed food in an allotment

in St Leonards. Photo Paul Tucker. 1916 was the Tercentenary of the death of William Shakespeare. Exeter celebrated the occasion, just weeks before the mass losses at Jutland and the Somme.

1916 was the Tercentenary of the death of William Shakespeare. Exeter celebrated the occasion, just weeks before the mass losses at Jutland and the Somme. The famous Deller's Café in Bedford Street opened in 1916.

The famous Deller's Café in Bedford Street opened in 1916. Workers of the City Collar Works – women were needed to keep the economy working.

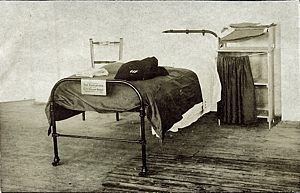

Workers of the City Collar Works – women were needed to keep the economy working. A VA hospital bed sponsored by the workers of the City Collar Works.

A VA hospital bed sponsored by the workers of the City Collar Works.

│ Top of Page │

1917 - Waltzing Matilda

The year got off to a cold start, when the River Exe froze over. The ice supported 100 people walking on its surface, and an ox was roasted on the surface. The City Council were concerned about the danger to life by people venturing onto the ice and arranged for ladders, boards and lifebelts to be placed on the bank, in case of emergency. It was considered that ice that was three inches thick was safe, and most of the river and canal, apart from under the bridge and by the ferry was frozen over to a depth of 3½ inches or more.

A local tragedy grabbed the headlines on 7th March 1917, when the 11am tram from Heavitree to Dunsford Hill lost control while descending Fore Street Hill, overturning on the Exe Bridge. One woman was killed in the tram crash, to add to the millions killed on the Western Front.

Exeter was out of reach of the increasing number of bombing raids by Zeppelins along the east coast and London, and consequently the Natural History Museum in Kensington feared for its collection. The curator of mammals, Mr R Oldfield Thomas arranged for the majority of type specimen mammals and a large number of small animal specimens to be transported to the Royal Albert Memorial Museum for safe keeping, and he moved down to Exeter to take care of them.

Food food, glorious food

Food continued to be a problem, or rather a lack of it, and the Express and Echo carried an advert in the January headed 'Meatless Days'. It went on to encourage people to buy dried and salted codfish from Newfoundland, which had as high a nutritive value as meat, for half the price. Also in January, the City Council announced that an additional ten acres had been acquired for allotments, which would be let in ten yard plots to about half of the three hundred on the waiting list. The need was greatest in St Thomas where the demand was greater than the supply, and 32 plots were allocated in St Thomas' Pleasure Ground. The rent for a plot was between 9d to 1s 6d a yard, and the Council would arrange for seed and manure to be available at wholesale prices.

Casualties mount

Because Exeter was on the main railway to the ports of Plymouth and Falmouth, many soldiers from Australia, New Zealand and Canada passed through on the way to the front. The city's five military hospitals were also kept busy as the war progressed, and numerous injured Australian, New Zealand and Canadian troops returned to Exeter to be treated in the VA hospitals.

The wounded arrived by train at Queen Street station - during 1917, many would disembark suffering from gas poisoning. The men would walk, blinded by the gas in a long crocodile, holding on to the man in front before being taken to their designated VA Hospital. Hobbling, recuperating men could be seen on the streets, wearing blue uniforms with a red tie to distinguish them from soldiers on leave or passing through the city to the front.

Frank Ritter recalls in his memoirs, of his mother noticing many convalescing soldiers passing their small store in Magdalen Street, close to VA Hospital No 1. His family had struggled to make a living from selling cigarettes and sweets, so his mother put a notice in the window advertising 'Teas'. Soon the shop was heaving with Australian soldiers enjoying a couple of hours away from their wards, chatting, drinking tea and singing Waltzing Matilda.

Australian and New Zealand soldiers did not forget Anzac Day, when on the 25th April, they assembled in front of the great West Window, to attend a service in the Cathedral.

Entertained by Propaganda

The cinemas were popular, and would have been full

of recuperating soldiers. The City Palace in Fore Street showed a

French propaganda film about gun manufacture, which proved to be very

popular. The film showed the production of British guns using "mammoth hammers" and "huge lathes for turning and boring".

Another film on the same bill, took a comic look at the Kaiser.

Many men from Exeter, both ordinary and prominent joined the army

to

fight for King and Country. Thomas Moore, who founded the clothing shop

in Fore Street had become well known before the war, driving his

Triumph motor cycle around the city. He joined up as a despatch rider,

only to be killed in 1917 at the Battle of Zillebeke. His name can

be

found on the memorial outside St Olave's Church in Fore Street.

After almost 145 years of informing Exonians of the local and national news, Trewman's Exeter Flying Post ceased publication on 21st April 1917. The name would resurface as an alternative, monthly magazine in 1975.

At St Sidwell's School, Minnie Simpson was given a prize certificate for knitting scarves and socks for soldiers on the front. In October, the Headmaster of Newtown Boys' School sold 3,000 war savings coupons.

April 25th 1917 - Australians assemble outside the Cathedral for Anzac Day.

April 25th 1917 - Australians assemble outside the Cathedral for Anzac Day.

Nurses at VA Hospital No 3 circa 1917.

Nurses at VA Hospital No 3 circa 1917.

Nurses and wounded soldiers also VA Hospital No 3 circa 1917.

Nurses and wounded soldiers also VA Hospital No 3 circa 1917. One person died when an Exeter tram crashed on the Exe Bridge in April 1917.

One person died when an Exeter tram crashed on the Exe Bridge in April 1917.

│ Top of Page │

1918 - Peace breaks out

In January, the River Exe suffered its worst flood in 34 years, then in February, heavy snow fell on Exeter, and the weary people prayed for peace.

The war dragged on and the carnage continued in the trenches of the Western Front. In Exeter, those with men in the forces would dread the ring of the telegram boy. In January there was a shortage of food across Devon and in April, the national rationing of meat, sugar, butter and margarine was introduced.

Influenza

Then a new enemy raised its ugly head - influenza swept through the country during the summer and autumn of 1918. On 25th July, 42 people were reported to have died from the influenza in Exeter.

The Medical Officer of Health closed 516 schools across the county; Newtown School had a five rather than four week summer break, and was closed for six weeks from the 8th October. It wasn't until the end of November that the influenza epidemic subsided.

The Eleventh Hour

And so, the eleventh hour of the eleventh day, of the eleventh month arrived.

News of the Armistice had been expected on Sunday 10th November, but it was obvious by 11pm that agreement had not been reached, and the expectant crowd in the streets of Exeter dispersed.

At 10.48am the next day, a bulletin was posted in the window of the Express and Echo office in the High Street reporting that the Armistice had been signed, and that all hostilities would cease at 11 am - within moments, the crowd had erupted with joy.

A jubilant mass of people milled about as the Exeter City Silver Band, at the Guildhall entrance played 'O God our help in ages past'; and the crowd sang along with joyous relief. The Stars and Stripes, the Colour's of Belgium, and the Tricolour of France were hauled up the flagpoles of the Guildhall, with the Union Flag flying above.

Exonians poured in from all over the city, children carrying flags, servicemen dancing jigs and office workers in their starched collars shouting with delight. By 1 pm, all business had closed for the day. In the afternoon, confetti was thrown in the streets and the trams were festooned with flags. A service of thanks giving was quickly organised in the Cathedral, where 3,000 attended.

Four years of war were over at last, a war in which of the millions who had lost their lives, 950 men and women were from Exeter. However the 11th November 1918 had a sting in the tail for the family of Captain Charles Frederic Anderson Hooper, who was the last casualty from Exeter, during the Great War. Deaths would continue for several more years as men died from wounds or disease contracted during their service at the front.

Three years later,

in May 1921,

the Prince of Wales

unveiled the Devon War

Memorial in Cathedral Yard to remember the fallen of the war to end all wars. The Exeter War Memorial was dedicated in April 1923.

Sources - Exeter Flying Post , Express and Echo, Devon in the Great War by Gerald Wasley, an Exeter Boyhood by Frank Ritter, St Sidwells School Exeter by Hazel Harvey, The Story of British VAD Work in the Great War by Thekla Bowser, Germans in Britain since 1500 by Panikos Panayi, Museums and the First World War by Gaynor Kavanagh, Willingly to School by Judith Sturman and Stephanie Barnes, People Talking by Jenny Lloyd and other articles on Exeter Memories.

The Mayoress Mrs J G owen, and fellow fundraiser, outside St Pancras Church.

The Mayoress Mrs J G owen, and fellow fundraiser, outside St Pancras Church. A group of wounded Canadian

soldiers thought to be from VA Hospital No

3 - circa 1918. They are wearing the blue jacket and red tie that were

issued to wounded troops. Photo Tamsin Harvey.

A group of wounded Canadian

soldiers thought to be from VA Hospital No

3 - circa 1918. They are wearing the blue jacket and red tie that were

issued to wounded troops. Photo Tamsin Harvey.  The Exeter Cycling Club built a huge bonfire on the 19th July 1919 on the golf

course at Pennsylvania to celebrate the end of the war. Courtesy of the

Westcountry Studies Library.

The Exeter Cycling Club built a huge bonfire on the 19th July 1919 on the golf

course at Pennsylvania to celebrate the end of the war. Courtesy of the

Westcountry Studies Library.

│ Top of Page │