Reed Hall

Formerly Streatham Hall, Duryard Lodge and Mount Stamp

Researched and written by David Cornforth

Page added 21 October 2017

Exeter University is built on high, rolling, and formerly forested ground known as Duryard. The land was owned by the City Chamber, and timber from the hills used in many projects around the city. It was an ideal place to build a grand house, away from the smoke and grime of the city, suitable for a gentleman.

Exeter University is built on high, rolling, and formerly forested ground known as Duryard. The land was owned by the City Chamber, and timber from the hills used in many projects around the city. It was an ideal place to build a grand house, away from the smoke and grime of the city, suitable for a gentleman.

The first intimation that a new property had been added to the Duryard landscape was in June 1770, when the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette carried an advert for a dwelling named Duryard Lodge, ‘a capital mansion-house’, that had been for a great part, newly built. This implies that there was previously a smaller property on the site. It was in a prime position that overlooked the City of Exeter, the River Exe and the ocean. The house had a coach house, stables for ten horses, offices and gardens. The whole was set in 36 acres of rich pasture land.

By 1792, the tenanted house was up for sale again–although advertised as Duryard Lodge, an alternative name for the house was given as Mount Stamp. The tithe map for 1839 shows two properties, one named Duryard Lodge the other unnamed–could this be Mount Stamp. At the end of the 19th Century, a farm in Lower Hoopern Valley was owned by the Stamp family, which may be a source for the name.

In 1797, the tenant was Lewis Knight, Esq., who had been Provost Marshal General in Jamaica, and listed as a slave owner in 1786. Duryard Lodge would have been a gentile retirement home after working in the colonies. By 1806, the tenant, Thomas Maxwell, a member of the privy council of Barbados, was buried in St David’s Church. He was married to Anne St John Trefusis, sister of Lord Clinton.

John William Williams Esq., mayor of the city in 1815 and director of the West of England Fire and Life Insurance Co., owned the house in 1822. A prominent tenant in 1833, was John Edye, a surgeon, who practiced in the city for many years. When his wife died in 1833, the house was for let.

‘Iron Sam’ Kingdon, as he was colloquially known, had run Kingdon and Sons iron foundry in Waterbeer Street for many years. As a non-conformists, he and his brother had applied themselves to trade, expanding the business that they inherited from their father. Non-conformists were excluded from the political life of the city, but with his success in commerce, Iron Sam became the first non-conformist to be mayor in 1835. This required a house commensurate with his position and on 3 September 1835, Duryard Lodge was sold by auction to Samuel and his brother, William Kingdon. The products of Kingdon and Son were incorporated into the house, in the form of cast iron balconies, and probably, one of their popular cast iron stoves. In 1849, Iron Sam retired, and the foundry sold–it became Garton and Jarvis, and then, in 1865, Garton and King, a name that will be mentioned again in the story of the house. Iron Sam died in 1854, while his widow remained in Duryard Lodge until her death in October 1864. The executors of her will put the house up for sale in 1866.

Streatham Hall is built

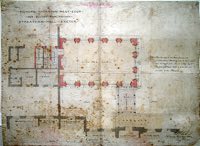

The new owner of the house was Richard Thornton West, a former East Indian merchantman, who had lived for many years in Batavia. Thornton West had inherited £1 million from his uncle, so with his gains from Batavia, he was a wealthy man. He soon had plans for a far grander residence than the old Duryard Lodge. It was reported in the Western Times on 11 June 1867, “Duryard Lodge, the residence of S. Kingdon, Esq., is a thing of the past, the building being razed to the ground.” A new house was to be constructed on a site a little to the south and west of the lodge, by Mr. W. Moore, of Fore Street, who was also the architect. A large Italian style villa, constructed of Westleigh stone, and white brick and Portland stone, was supervised by Mr. Hunt, the clerk of works. All traces of Duryard Lodge were removed, including the name, as Streatham House rose on the hillside of Duryard. The foundation stone was laid on the 7 June by Thornton West’s son, Richard Bowerman West, aged two and a half. As is usual on these occasions, a grand dinner, supplied by Mr. Cuthbertson, was laid on in a marquee, for the 150 workmen. The cost of the house was £80,000, while the landscaping and gardens, by the Veitch Nursery was £70,000–Thornton West was determined to build a property of substance.

Garton and King, in their foundry in Waterbeer Street, manufactured stoves and heating systems. They were contracted in 1869 to fit a heating system for the hothouses, that had been constructed in the grounds. Their equipment heated the forcing pits, for early fruit including vines, and vegetables, and the mushroom house. Having created a house that was the envy of the city, the family moved in during April 1869. Having spent so much money, Thornton West found enough small change to donate the cost of a first-class life boat station, to be placed on the coast of Devon or Cornwall for £700.

Further improvements were made to the house in 1878, with the addition of a billiard room at the rear, part of which was constructed of cast iron pillars manufactured by Garton and King. The company also installed a heating system, utilising waste heat from a conservatory. Thornton West died in November 1879 at the age of 65, leaving his wife Sarah and young son Richard Bowerman West.

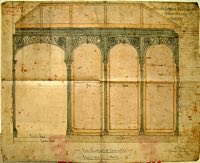

The Palm House

In 1891, the Palm House, designed by E H Harbottle, was added. Measuring 71ft by 40ft, it contained what was described as tropical rockwork, arranged by Messrs. Robert and Son of the Royal Nursery in Exeter. Rocks, some weighing several tons, were brought from across Devon. The largest palm was 30ft tall, while the rocks were covered in green moss, interspersed with ferns. The tropical plants were provided by the Veitch nursery. This iconic structure remained until 1926, when it was sold and moved to the Imperial Hotel, and is now known as the Orangery.

Richard Bowerman West became High Sheriff of Devon before he died at the early age of 35 in 1900, and was buried in St David’s Church. His mother, Sarah West died in December 1902, and she left the house to her sister Mrs Eames, and her brother Mr Richard John Bowerman. The house was put up for sale in April 1903. In comparison with Duryard Lodge, which it replaced, Streatham Hall had grown into a very large and extensive property, as this sales description testifies.

“It contains entrance and inner halls, five elegant reception-rooms, magnificent billiard-room, 27 bed and dressing rooms, and extensive domestic offices and cellarage. The Mansion is surrounded by the most beautiful pleasure grounds arranged in terraces, and including an exquisite Italian garden, with lake and superb conservatory and palm house. There are extensive fruit and vegetable gardens …”

The auction was on the 24 September 1903 at Poples New London Inn. The particulars stated that it was worth an estimated rental income of £1086. Bidding went up to 18,000 but it didn’t make the estimate and was withdrawn. Richard Bowerman continued to occupy the house.

Mr Bowerman, and the sons and daughters of the late Mrs Eames, formed a syndicate for the estate, less the house, and surrounding 11 acres plus the Hoopern Valley. The syndicate, that consisted of Mr Bowerman himself, and Mr C E Rowe, the Mayor Mr W H Reed, Mr Hancock, Mr Shrimpton and Mr Bowden, took control of the 278 acres surrounding the house. They intended to develop the land for building, between Streatham Hall and Cowley Bridge Road.

Streatham Hall and the Hoopern Valley were offered to the City Council for £17,000, who had previously intimated their interest for use the house as a Men’s Hostel for the Day Training College and building land for the valley. Matters dragged on until August 1908 when a vote to purchase the hall was lost by only one vote. Unfortunately, the council could not agree on the valley, and yet another committee was formed.

The First World War

During the years up to the First War, the grounds of the hall were used for hosting many events. Fetes for supporting lifeboats, the YMCA, temperance societies and local hunts were held, often on an annual basis. Then in August 1914, the hall was requisitioned as accommodation for troops. The newspapers recorded the tragic death of a 19 year old soldier, who fell out of an upper window, as the result of a bet, in November 1914.

By 1917, war casualties were mounting, and in the April, Streatham Hall was converted for use as VA Hospital No 7 for officers, as would have befitted its grand elegance. Land for 21 allotments was released from the estate in 1918, as part of the drive to produce more food, due to the U-boat blockade. The hall was still in use as an officers’ hospital in 1919, although by the July, only bedridden cases remained. They were entertained during the Peace Celebration, on 21 July, by local entertainers, and some talented inmates and nurses. Two days later a historical pageant, ‘The Home Comers’, was held in the grounds. By Christmas there were still 50 or 60 men split between Streatham Hall and the Bishops Palace, VA Hospital No 6. Another year passed, and wounded soldiers were still at the hall, with appeals being made in the newspapers for funds to entertain the them.

The Prince of Wales, while in Exeter, unveiling the Devon War Memorial, in May 1921, visited the wounded at the hall, where he shook hands with every man, and remarked that he was “charmed by the excellence of the building.”

The next year, Mr W H Reed JP, a partner in the Express and Echo, and paper manufacturer, purchased the Hall from the Thornton West family. He immediately presented it to the University of the South West, then based in Gandy Street. By October 1922, Sir Henry Lopes, Chairman of the Governors of the University, stated that he looked forward to attending a social in the new College premises at Streatham Hall. By December, the military had moved out and the Hall was being prepared for its new role as a hall for male students at the College. It was probably around this time that the palm house was taken down and rebuilt at the Imperial Hotel, and renamed the Orangery.

This single act was responsible for what would become the University of Exeter occupying what was known as the Streatham Campus. Reed did not see the development of his gift into a place of learning for he died in May 1923. He had taken a keen interest in education as a member of the committee of the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Chairman of Governors of Queen’s College, Taunton. Streatham Hall was finally named Reed Hall in March 1925, with a capacity for 70 male students–its first intake was to be the next October. Over the next years, the university expanded, as new facilities were added to the Streatham Campus.

The Second World War

At the outbreak of war, many young men were joining the forces, deferring their education until the end of hostilities. Reed Hall was again requisitioned for the war effort, and became a centre for the dispersal of the blind who had been evacuated from London. Students were still occupying part of the building, when in June 1940, after they had gone down for the long vacation,180 boys from Westminster School moved in to Reed Hall and Mardon Hall, with their headmaster Mr J T Christie. The boys were taught in the Gandy Street premises of the College. In September the Central School for Speech Training and Dramatic Art, comprising of more than 70 female students moved into the Hall.

Later in the war, medical students were also housed in the Hall. There were social events held there during the war years, and Joe Louis, the boxer attended a concert at the hall, in 1944, when the Glenn Miller Band played for US troops.

The College of the South West became a University in 1955. Since then, it has expanded to 20,000 students, with Reed Hall now a meeting and conference centre. The gardens still exist, giving a quiet, green space for contemplation on the edge of a busy campus .

Sources: The British Newspaper Archive, The Story of Exeter by Hazel Harvey, reedhall.co.uk, Country Life Illustrated - April 1899, Richard Holladay.

│ Top of Page │