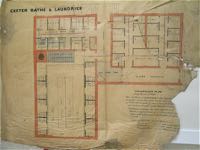

Public Wash-house, King Street

Page updated 21st May 2016

The far end of King Street, beyond where the street

crossed Rack Street, was the site of the public wash-house, which

opened on 9th August 1852. Plans were first discussed at a meeting at the Guildhall in January 1850, when the Dean of Exeter said "his heart (was) entirely in it". The driving force and treasurer for the enterprise was John Dinham, a

philanthropist who would do

much for Exonians during the next few year. Garton and Jarvis were contracted to fit the building out with hot and cold pipes, baths, vapour baths, toilets, laundering facilities and a boiler.

The far end of King Street, beyond where the street

crossed Rack Street, was the site of the public wash-house, which

opened on 9th August 1852. Plans were first discussed at a meeting at the Guildhall in January 1850, when the Dean of Exeter said "his heart (was) entirely in it". The driving force and treasurer for the enterprise was John Dinham, a

philanthropist who would do

much for Exonians during the next few year. Garton and Jarvis were contracted to fit the building out with hot and cold pipes, baths, vapour baths, toilets, laundering facilities and a boiler.

The manager for many years was a Miss Elizabeth Lemon who lived in Tighe Place. A local policeman, Thomas Ford, became an engineer and by 1861, lived with his family in the same house as Miss Lemon, as a bath house keeper. By 1902 the wash-house superintendant was Miss A L Purkis.

The Earl of Fortescue visited the wash-house in 1856 and donated £10 towards its upkeep; the facility was in debt and having been founded as a charity, required the local great and the good to contribute towards the running costs. By 1875, the Baths and Wash-houses Committee reported that there were an average 17,000 washers and 10,000 bathers per year.

The wash-house in the 1880s had six first-class and eight second-class baths for men, and eight baths for women, including two vapour baths. There was room for nineteen washers, each supplied with hot and cold water, in the laundry which was supplied by a steam boiler, a hot air chamber and a large, communal ironing board. The charge was a penny per hour for laundering, and between a penny and sixpence for a cold or warm bath.

In 1975, Mr Bartlett of Shilhay was interviewed about his memories of the area and he recalled this about the wash-house in the 1920s.

"There were two entrances, one from Tighe Place and the other from Albert Place up a long row of steps beside Mary Magdalen Church. You went into a large place almost as big as the main hall at the Mission and all the way round there were wooden cubicles where the women did their washing. In each there were three containers; one had warm water for washing; one on the left hand side had boiling water heated by a steam valve operated by a little wheel (and if the women opened it too quickly they stood a chance of getting a blast of steam over them); on the other side was a clear tub for rinsing the washing. In the centre of the wash house were two wringers, each bigger than an easy chair. The women put all their washing in as tightly as they could and put something heavy like a blanket on the top. then they would give a wave to the stoker, Mr. Bowden, and he would pull his levers and work his little bits of machinery and off would go the wringers, spin drying. This was worked by steam and the water would rush out of a vent in the bottom. If a woman had not packed her washing tightly enough or put the blanket on top in time, the washing would fly out all over the wash house and she would have to do it all again. After it was spun, she could get a 'horse'. This was like an outsize clotheshorse, pulled out on slides. She could hang her clothes on the rails and push these in so that they dried in the steam heated compartments; it did not take long to dry as it was so hot there. Beside he entrance to the wash house was the entrance for the ladies' baths. Children up to about 4 or 5 would go in the ladies' side. You went up to a pay desk, the superintendent would run the water (he used a spanner as there were no taps) and you would be shut in your own little cubicle. The men's baths were round the other side of the building. Charges were 2d. for a bath, washing about 6d. spinning a 1d. and drying 2d."

The cholera outbreak of 1832 resulted in five in King Street dying of the disease, The installation of improved facilities such as the public wash house did reduce further epidemics, but serious disease still stalked the street. In December 1871 two cases of small-pox were reported, one in King Street. The victim had been removed to Whipton for care, and the medical officer for the Workhouse reported, at the same meeting, an increased number of sick people admitted into the institution's hospital. In 1885, a case of scarlet fever was reported in King Street, and, although not an epidemic, it was not an uncommon occurrence.

Source: Various sources including Victorian Exeter by Robert Newton, the Flying Post, notes from the Exeter Industrial Archaelogy Group 1975 and Colin Barry.

│ Top of Page │