Exeter Lime Kilns–St Leonard's Quay

Updated 12th October 2015

Return to Industrial Exeter

Lime burning for both agriculture, and building goes back to at least the Romans. There were several lime kilns around Exeter; Countess Wear, Topsham and on the canal bank near Exminster being three well known locations. The most central were the kilns just above what was known as St Leonard's Quay, a few yards up river from the Port Royal pub; indeed there is evidence of a kiln by the Port Royal itself.

Donn’s map of 1765 indicates at least two kilns from the site of the Port Royal to about 75 metres upriver. Behind the flat area of the lime kilns, there was a steep rise to a rack field owned by Charles Bowring.

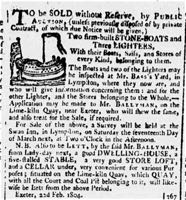

Newspaper records before 1800 are not generally available. The earliest after 1800 is an advert in 1802 to let the lime kilns “a little below the Quay”. Included in the let were two stone boats, three lighters with sales, ropes etc., carts. Mr William Ballyman was named as the contact and was one of the proprietors. By the end of the year an advert appeared (see left) that the kilns had not been let, and that the equipment would be sold, and the kilns and buildings let for other uses. It would appear that the kilns were eventually let, and lime was continued to be burnt.

Newspaper records before 1800 are not generally available. The earliest after 1800 is an advert in 1802 to let the lime kilns “a little below the Quay”. Included in the let were two stone boats, three lighters with sales, ropes etc., carts. Mr William Ballyman was named as the contact and was one of the proprietors. By the end of the year an advert appeared (see left) that the kilns had not been let, and that the equipment would be sold, and the kilns and buildings let for other uses. It would appear that the kilns were eventually let, and lime was continued to be burnt.

Before the opening of the Port Royal, the lime burners of St Leonard’s did not have far to go, for a drink. On the river bank, at the bottom of what is now Colleton Hill, was a public house named Knave of Clubs. It later became the home of Robert Dymond's (solicitor and historian) father.

Building boom

In September 1832, a third share of the kilns, coal and culm yards were for sale (culm is a poor quality coal related to anthracite). The advert noted that there were eight kilns, two houses, a counting-house, cellars, stables, shed, a landing stage. In total, the river frontage was about 390 ft, and about 90 ft in depth. The proprietors were Mr Williams and Mr Ebbels. It would appear that the kilns had considerably grown since 1802, and the cutting of the canal to Turf, and the opening of the basin, made shipping lime in from Berry Head and coal from South Wales easier. There had been a building boom in Exeter in the first half ot the 19th Century, so a reliable supply of lime was needed. Lime was carried through Exeter, up South Street and down North Street to St David’s down for agricultural use, on trucker mucks; a trucker muck was a wheel less cart that dragged on the street. James Cossins remembered that in 1827 "The traffic up and down (North Street) was almost incessant. I have seen from 12 to 20 pair horse carts in succession, laden with lime, coming from the St. Leonard's and Countess Wear kilns."

A third partner was not found–two years later, in 1834, Robert Dymond, the executor of Mr Williams, upon William's death, disposed of the business to Messrs. Hooper and Ebbels. Hooper had built Chichester Place in Southernhay in 1820, and had become a well respected builder in the city. It was common for builders at that time to produce their own lime and bricks, so a partnership in a lime kiln made sense. By this time there were four working kilns, indicating that trade may have been in decline.

The partnership of Hooper and Ebbels ended in May 1844 by mutual consent, with the Hooper’s (William, Henry and William Wills) agreeing to pay all debts. Sometime after a George Warren took over the kilns and was well established by 1854. In 1857, the stone boat, timber barge named Majestic at 49 tons, a lighter of 60 tons with sails anchors etc., lying at the quay were for sale as the George Warren had no further use for them. That was the end of the kilns. Warren also lived in Lime Kiln Lane and 1, Baring Terrace. He died in 1891. One map of 1850 shows Larkbeare Lane named as Lime Kiln Lane.

Above the kilns was a large rack field that belonged to the Bowring family. In 1862, John Charles Bowring embarked on building Larkbeare House on the land; he acquired all the land down to the river, and the kilns, which were probably inactive, closed for good. The flat area behind the wall was filled in when the top was flattened to make way for the house. This was the end of lime burning in Exeter, an industry that was both dangerous and dirty. It was superseded by centralised large industrial lime kilns for cement making.

Sources: 19th Century Newspapers from the British Newspaper Archive and various trade directories. Reminiscences of Exeter 50 Year Since by James Cossins.

There are no pictures of the lime kilns. Roque's map of 1744 shows the kilns. There appears to be two kilns marked on the map.

1805 Hayman's map shows the kilns between the river and the Bowring rackfields. This map seems to indicate five kilns.

│ Top of Page │