Exwick's 'County Steam Laundry'

also a Fulling Mill, Paper Mill and Corn Mill

Page updated 11th November 2013

Back to Mills of Exeter or go to the Map

Until my research into the origin of this mill, nothing was known of who first built a mill on the leat in Exwick village. This history is based on several years research using original documentation as the main source.

The naming of the various mills in Exwick has caused much confusion with historians, but some careful teasing out of the evidence unearths the Exwick Lower Mill's existence as a fulling, paper and corn mill before it became the County Steam Laundry. The mill was situated opposite Exwick Hill, on the east side of St Andrews Road, on what is now Riverview Drive.

The Fulling Mill - 1673

In 1673, Benjamin Oliver of Exeter, and Robin Ridler of St Thomas, signed a 99 year agreement to allow the construction of a fulling mill, by Anthony Mapowder, Joseph Pince and John Ridler, on a plot of land 36ft by 10ft, to the east of the leat. The land was on the leat, in Little Meadow, at the bottom of Exwick Hill, and close to Exwick Manor House. Three years later, Oliver extended the lease to 99 years, to Thomas Heath, Joseph Pince and John Ridler for the existing fulling mill, and a new grist mill also to the east of the leat. Oliver held the lease of Exwick Manor, part of which belonged to the Gould family of Downes.

The next generation of merchants to work the mill included Richard Mapowder, a clothier and several others. In 1720, they appear to have given up the lease, to the land owner, William Gould of Downes, for the sum of £100.

Forty five years later, in 1765, a lease was signed for what had become known as the Lower Mill, on the same site, from John Tuckfield to Alderman Joseph Elliot for a shamoy (chamois leather) mill and millhouse, wheel, two stocks and a mill meadow of 2½ acres. Tuckfield, of Little Fulford, married Frances Gould, the second daughter of William Gould of Downes, and hence her estates in St Thomas and most of Exwick, including the mills, passed to Tuckfield on marriage. The elder sister, Elizabeth Gould, Tucker's sister in law, married James Buller – when Tuckfield and Francis died, without issue, his estates came into the possession of the Buller family.

Another lease, the same year for the adjacent mill, was also from Tuckfield, this time to John Baring of Mount Radford. The lease to Baring assigns two fulling mills and a mill house consisting of two wheels and the four stocks of Richard Mapowder, a clothier, and Thomas Jeffery, a merchant, who ran what was commonly known as Mapowder's and Jeffery's wheels. The lease goes on to mention that this mill was on the site of another fulling mill, "now destroyed called Pinto's wheel...".

John and Charles Baring's wool business was not very well documented in the second half of the 18th Century; Charles was ostensibly in charge of the Exeter end of the Baring's business interests, but he proved to be a poor businessman, during an era when the woollen trade was proving to be very volatile; however, it is likely that Baring's mill was the same same one that Antony Gibbs later leased for a time from James Buller in 1785, while building his woollen factory 'empire'. In 1805, the Sherbourne Mercury carried a lease for sale for the four fulling or shamoy mills, still leased by Baring and Co.

The Paper Mill and Thomas Bedford Pim

In October 1804, Thomas Bedford Pim leased the old shamoy mill for the manufacturing of paper; a former fulling or shamoy mill was ideal for paper-making as the fulling stocks could be easily converted into beating engines, which were used to break up the fibres of the rag. An insurance policy for the same year indicates that at this time the mill was stone with lath and plaster, boarded and with a slate roof. In 1807, Pim leased the adjacent fulling mill from James Buller.

Several namesake's of Pim already produced paper in Exeter, with Edward Pim running Head Weir Mill from 1798 and a John Pim in partnership with others at Countess Weir Mill at the same time. Thomas Bedford's mill was not the first paper mill in Exwick, for a paper mill existed in 1673, along with eight fulling mills on the site of the Higher Mill. Eight fulling mills is not eight buildings, but rather it is eight fulling stocks.

In the same year Pim married Elizabeth Finch, the daughter of Richard Finch, and he settled down to produce a son named Edwin Bedford Finch Pim, and two daughters, and run his business. In October 1808, he was listed as a holder of a game licence, a useful way of supplementing the pot in a rural area.

A fire at Pim's mill broke out on December 4th 1809, which was investigated as arson, with Mr Pim as the possible suspect; in the event, it was not proven. The Flying Post reported the event thus– "On Monday evening, about six o'clock, a most alarming fire broke out in the extensive paper-mill belonging to Mr. Thomas Pim, at Exwick, near this city, which raged with such fury, that the whole of the building, together with an immense stock of paper, were entirely destroyed before the fire could be got under. The flames were prodigious, and the sight awfully grand and tremendous, flakes of fire and bundles of paper were carried blazing into the air, threatening destruction to the whole village, but which was providentially preserved with the exception of two joining cottages. The premises were insured to a large amount, but we hear very inadequate to the loss sustained."

Pim quickly rebuilt the mill and resumed paper manufacturing, until 1813 when he became insolvent and was petitioned for bankruptcy; events took another turn, when he was prosecuted by the Hope Insurance Co for a fraud related to the fire in 1809. It was alleged he committed perjury, having taken out two mortgages on the property without telling the company. Pim was found guilty on 31st March and awaited sentencing. On December 1st 1814, he was sentenced to serve 2 years in the Devon County Gaol.

It is not known if the mill closed down while Pim was incarcerated, but it is possible his wife managed to keep it running by employing local paper makers. In January 1817, having been out of prison for a few weeks, he was formerly declared bankrupt. Pim would not have been allowed to run his business, so in 1818, his father-in-law Richard Finch leased the mill from the Buller estate, and Thomas Bedford Pim continued to produce paper.

In 1821, Finch surrendered the lease to Buller, allowing his son-in-law, Pim could lease the mill in his own right, as he had paid off his debtors. At this time, Pim's mill was producing course, poor quality paper made with 30% flax straw. At some point he seems to have gone into some sort of partnership with Charles Squire.

Pim was fined £1,000 for avoiding to pay excise by "removing paper before charged with duty," on May 1st 1823. Having paid one fine for evading duty, Pim was then caught for a second time and on September 16th he paid another £500, this time "... for removing paper without payment of duty." On January 22nd 1824, he was fined for a third time, along with Charles Squire, by the Revenue "... for using a forged stamp for paper labels, &c." a total of £1,000, a sum he couldn't pay. Three days earlier he had to auction, under duress, 66 dozen bottles of old port and sherry, on orders of the Sheriff of Devon. Pim was in real trouble and a few days later he was declared bankrupt for a second time. Further, it was reported on April 2nd 1824, that three of Pim's apprentices had applied for the back payment of their wages; his attorney undertook to pay the money, and to cancel their apprenticeship if work was not found within a week.

Pim's father-in-law did not save him this time, and the mill was taken over by his former partner, Charles Squire, who seems not to have been involved in the bankruptcy, from October 1824. By May 1826 William Henry Pim who ran the Head Weir paper mill took on the Exwick mill, which he ran until 1832. He appears to have run the mill without incident, but in 1820, while running the Head Weir Mill he managed to tangle with the Revenue regarding the shipment of paper from Topsham without paying the duty.

As a footnote to the life and times of Thomas Edward Pim, in 1832 he applied to be discharged from his bankruptcy, but was refused, on the basis that his application papers gave his name as Pym; he was accused of trying to deceive the hearing, and facetiously told he would be prepared to use the name Jones if necessary.

It was during the late 1820's that Exwick House was built on Field Meadow, land that belonged to the mill, and thus becoming the mill house. In 1832, the Times carried an advert for the mill, with '... a modern and substantially built dwelling house' and land, for sale. The advert listed the machinery including three drying cylinders, a steam boiler and washing and beating machines. It also includes the phrase 'fitted up with machine' which referred to the Fourdrinier continuous paper making machinery that had been invented in 1806.

The Exwick Martyrs

Richard Matthews and his new son-in-law, Samuel Chubb, took on the lease in 1832; Matthews already ran a thriving paper mill in Huxham, leaving Chubb to establish himself with his new bride at Exwick, trading as Matthews and Chubb. All was going well until the next year, for just a month after the Tolpuddle Martyrs were arrested for refusing to work for higher wages, Chubb narrowly avoided creating the Exwick Martyrs.

In March 1834, four of their journeyman paper-makers, Thomas Cripps, James Norman, John Barbor and Richard Smith were taken to court charged under the 1825 Combination Act with having 'quitted their employ without notice' and appearing to be members of a club or union. The men were in dispute over wages; on the previous Monday morning they turned out and paraded in the village with fife and drum – one can imagine them, followed by excited rag-a-muffin children, and their women folk encouraging them on. They were promptly arrested and appeared in front of George Truscott Esq. The Judge inspected the books of the mill, and agreed with Matthews and Chubb that the men were understating their wages. He objected to them combining together to halt production, and suggested that rather than imprisoning them for three months, he would discharge them, if they agreed to return to work. Then if they still felt aggrieved, he suggested they could give two weeks notice on the next Saturday; the four men agreed to comply, and unlike the men from Tolpuddle, they escaped transportation to Australia!

Another strike

In December 1836, another dispute broke out, this time, between all the paper makers of Exeter and the journeymen they employed. The men had issued a circular demanding 3½d per hour, or 17s 6d for a 60 hour week; they claimed that 6d per hour was paid in other parts of England. In addition, they wanted all women workers who were doing a journeyman's job to be replaced by men. The paper manufacturers refused, forcing the men to up their demand to 4½d per hour. At the end of the year, the mill owners advertised for one hundred and fifty men to learn the paper trade and replace the strikers. Matthews and Chubb were one of the concerns listed. The dispute appears to have fizzled out, with a few men forced to return to avoid destitution, while the paper makers reported that the new men were learning the trade quickly.

Samuel Chubb died in January 1840, leaving a grieving, and pregnant widow Catherine, and three young children. Even for folk from an industrious family could find their circumstances quickly change – one of Catherine's children went to live with his grandparents in Tavistock, while the unborn child would eventually live with her grandfather at Huxham, while the fate of the other two is not known. Catherine joined her sister at Beaufort House, Cowick Street as a school mistress, according to the census of 1841, and died at Huxham, aged just 34 in May 1844.

The mill was advertised for let in February 1841, and soon after, one Francis Edward Smith was the paper maker running the mill. By April 1843, Smith was also having difficulties as a the machinery and other equipment was for sale under a distress warrant.

Richard Matthews persuaded his younger son, George to take on the mill. Catherine moved to Cowick Street, into the household of Mary Pym, a school mistress. Her youngest daughter, one year old Caroline was living with her grandfather, Richard Matthews in Huxham in 1841.

The 1841 census shows the men working for Smith:

John Deviell 55 - paper maker

John Butt 55 - paper maker

John Vickery 60 - paper maker

The mill was referred to in an advert of April 1843, for the sale of paper making equipment and utensils, as well as rag, due to a distress warrant –it would seem that Francis Edward Smith had also found trade difficult.

The Exwick paper mill was a very small concern in comparison with Countess Wear Paper Mill which employed 39 locals, plus others from Exeter in 1851. The 1851 census listed the following paper makers in Exwick:

George Matthews age 37 - paper manufacturer

William Caryl age 38 - paper maker

Thomas Lang Caryl age 13 - paper maker

John Butt age 68 - paper maker

Mary Butt age 69 - paper maker

Sarah Taylor age 54 - worker in paper mill

George Matthews was the son of Richard Matthews, so he should have had plenty advise and backing to run the mill. A month or two after the census, in June 1851 George Matthews was also issued with a distress warrant from the Inland Revenue, for the sum of £361 19s 3½d. The Revenue made the application to ensure they were paid before the landlord received his rent. There is no record of Matthews filing for bankruptcy, so the assumption is that he ceased trading.

John Dewdney Jnr

The next owner of the mill was John Dewdney Jnr, who was from a line of paper makers. His father, also named John, ran the paper mill at Hele, near Crediton; he invented a method of producing glazed writing paper in the 1840s, which was used to print the catalogue of the 1851 , Great Exhibition, and for which he was awarded a gold medal. Dewdney Snr retired to Starcross in 1852, which may account for his son taking on the lease at the Exwick mill. In September 1853, John Dewdney Jnr married Miss Eliza Burgess at Illogan, Cornwall. His time at the Exwick mill is marked by various mentions for theft from him, in the Flying Post. The 1856 Post Office Directory notes that the mill, at this time, manufactured brown paper.

The 67 year old John Dewdney Snr was killed in an accident at Hele Station, on 9th June 1858, when he was run down by a fast down express, while crossing the line to catch a slow train back to his home in Starcross. The next month, on the 21st July, an auction was held of the furniture and household effects of his son, at Exwick, as he was leaving the district.The death of his father seems to have prompted his leaving paper making for good, and in the 1861 census, John Dewdney, aged 35, along with his wife and servant, is living at Camden Lodge, Peckham. He was listed as a Commission Agent in Paper.

The last paper maker

William Dawton was the last paper maker at the Lower Mill–the 1861 census lists Dawton as 40 years old with a wife and one daughter. He employed 4 men, one boy and 2 women. Dawton was fined £1,400 in July 1861, by the Revenue, for altering stamps on reams of paper to avoid paying the paper tax–this was a huge fine and he obviously could not continue trading. The census lists the following men working for William Dawton:

William Dawton - paper manufacturer (not on census)

William Harvey 36 - paper maker

Charles Panes 16 - paper maker

Henry Panter 31 - paper maker

John Deviell 78 - paper maker

Henry Ellis 30 - paper maker

In July 1862, Maunder's old woollen mill 60 yards further down the leat burnt down, and both mills were put up for sale in September 1862, "... extensive range of mill property... for many years occupied by Messrs Maunder as a woollen factory and Messrs Harris as paper mills, and are now to be let in consequence of the recent destruction of the former by fire..." The paper mill measured 100 by 60 ft and had two working wheels. Mr Harris was a paper maker from Countess Wear and probably the lessee of the mill, which he then had sublet for many years to John Dewdney, William Dawton and others. The mills were purchased by the Bullers of Downes.

The Corn Mill - 1869

The next record of the mill appears in 1869 when it was advertised for sale – it was 'newly erected with 3¾ acres of land and a commodious house suitable for any business that requires power.' A Mr John Horswell, a young miller and merchant from Plymouth took on the lease, moved into Exwick House, and ran a corn milling business until 1882 when he was declared bankrupt. In the same year, a Mr John R Rossiter, whose lease on his mill in Totnes had expired, was encouraged by one of his sons to take the vacant mill in Exwick; however, family differences were taken to court in 1890, when the son was the defendant and his father and brother the plaintiffs in a dispute over the partnership. Rossiter ceased milling and the mill became vacant.

The Steam Laundry - 1893

Mrs Jane Oldridge leased the mill from the Bullers in May 1893, the machinery was put up for sale in June 1893 and by September, it opened as the County Steam Laundry, managed by Mr and Mrs Frederick Edgar who lived in 2, Laundry Cottages. The first advert said 'The County Steam Laundry, Exwick, Exeter is now open for the reception of every description of laundry.... first-class steam laundry worked on sanitary principles.... also an extensive Meadow for Open-Air drying'

In January 1897 business was expanding for they advertised 'wanted, Best Shirt Ironers, piecework, 1s 6d per dozen'. In the 1891 census, before the laundry opened, there were several individuals listed as launderers in Exwick, and it may well have been these services that indicated a market for laundry services. An expanding middle class, as well as a hotel trade in the growing city of Exeter, and further afield in the new seaside towns, required laundry services, and Exwick was not the only suburb to provide such facilities. The 1901 census lists fifteen laundry workers living in Exwick and another fourteen working from home, probably as out workers processing delicate items.

A short article appeared in the Flying Post in April 1899 that stated that the County Steam Laundry had presented Mr and Mrs Edgar, on the occasion of them leaving to run the Grapes Inn in South Street, with a handsome silver tea and coffee service for their faithful service to the laundry. However, the Edgar's still appear as managers of the laundry in the local directories until 1916, indicating that the move to South Street did not happen.

Between 1919 and 1929, Charles Austin was manager, and then, in 1930, Mrs E Edgar is listed as manager, with Austin still living in Laundry Cottage. Mr Treviss-Smith moved into Exwick House during 1932, and in the next year he was listed as manager of the laundry, along with Edgar and Austin. 1934 saw a new manager, Mr R O Whittle take charge – he remained right through the war years until 1953.

A fire, on 2 December 1941, at the County Steam Laundry destroyed several thousand pounds worth of clothing, including officers' uniforms and workers' overalls, gutting the top of the building, but leaving the ground floor, and machinery, intact. Aerial photos of the time show the mill without a roof. It was back in operation within days, as accommodation at Exwick House was utilised for some of the work. Exwick Village Hall was let to the laundry for sorting clothing and linen, although it had to be cleared on Thursday evenings, for use by the Boys Brigade. This arrangement lasted about six weeks.

The laundry was often flooded and photographs from the 1950s show a laundry delivery van at the entrance, up to its wheel hubs in water. The County Steam Laundry (Exwick) Ltd, as it had become, continued until 1970, when Advance Towel Master (Western) Ltd took over the company. New services including linen hire and dry cleaning were introduced, but by the early 1980s it was obvious that the old mill was no longer a suitable building for a linen service company. Advanced Towel Masters relocated to Hennock Road, Marsh Barton in 1982 and in December 1982 this very visible remnant of a past age was demolished. Exwick House was sold, and divided into flats in the same year.

The fire damaged County Steam Laundry 1941.

The fire damaged County Steam Laundry 1941.

Workers in the County Steam Laundry in 1935 - the drums on the left may be dryers. Photo courtesy of the Exwick Local History Group.

Workers in the County Steam Laundry in 1935 - the drums on the left may be dryers. Photo courtesy of the Exwick Local History Group.

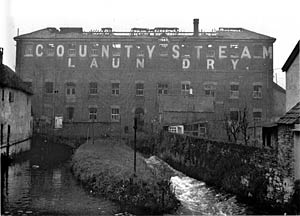

The

front of the Exwick County Steam Laundry just before it was demolished

in 1982.

The

front of the Exwick County Steam Laundry just before it was demolished

in 1982.

The old mill building from the

downstream side of the leat. Notice that the top floor has been

removed, and a flat roof added, after the 1941 fire. All photos

above courtesy Alan H

Mazonowicz

The old mill building from the

downstream side of the leat. Notice that the top floor has been

removed, and a flat roof added, after the 1941 fire. All photos

above courtesy Alan H

Mazonowicz

A water

wheel at the County Steam Laundry just before it was scrapped. Photo courtesy Pauline Green

A water

wheel at the County Steam Laundry just before it was scrapped. Photo courtesy Pauline Green

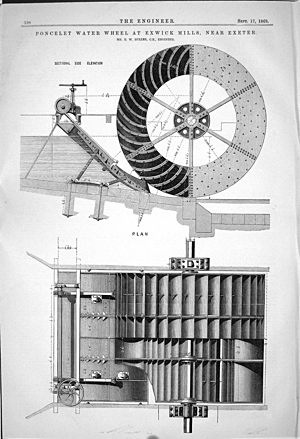

The wheel in the colour photo above was installed in 1869, to run a flour mill. This diagram was in The Engineer magazine.

The wheel in the colour photo above was installed in 1869, to run a flour mill. This diagram was in The Engineer magazine.  A County Steam Laundry

van in a flood during the 1950s. Photo courtesy Val Price

A County Steam Laundry

van in a flood during the 1950s. Photo courtesy Val Price Exwick

House where the Steam

Laundry relocated after the 1941 fire. It was built as the mill house

for the paper mill.

Exwick

House where the Steam

Laundry relocated after the 1941 fire. It was built as the mill house

for the paper mill.

│ Top of Page │