The Glasshouse, Countess Wear

Updated 22nd February 2015

Return to Industrial Exeter

Between 1681 and 1793 there was situated on the banks of the River Exe, a couple of hundred yards below the present Countess Wear Bridge, one and maybe three, large brick cones that were the hallmark of Exeter's long lost glass industry. Glasshouse Lane, was named in 1947 after the glasshouse which it once skirted. A careful inspection of the bounding wall by the lane will reveal that part of its structure is made up of vitrified fire-brick, that was used to build the cone.

The port of Topsham carried a good proportion of Exeter's main export, woollen cloth. The exports to Spain, Portugal and France would be reciprocated by wine imports from these countries. Hogs heads of wine would be landed at Topsham and at the port of Exeter and then bottled, Up until the glasshouse was commissioned, bottles were imported from Bristol and London.

Although the glass house was in operation from about 1681, by 1691, William Rennel, his son, Jos. Marshall, John Hopping, Richard Hele and John Ridler were listed working the glass house, while the owner was Richard Renell in 1701. It was for lease in the London Gazette on 22nd June 1702:

"A Round Bottle Glass House 94 foot high and 60 foot broad with all Conveniences a Pound House and small Smith's Forge a quantity of Pot, Clay and Working Tools for Bottles and Flint with two Stone built Dwelling Houses Two Gardens and three Large Orchards also Eight Acres of meadow Ground a large Kitchen Garden and Nursery with Barn Stable and Outhouses in Ware, between Topson and Exon, near the River, fit to carry and recarry the Goods. Tis to let at 7, 14, or 21 years. Enquire of Eliz. Rennell, at the Glass House, near Exon or of Isaac Barnard in Milk St, London"

Bottle seals from around Topsham have been found bearing the name Francis Davy, who ran the glass cone in the middle of the eighteenth century. Seals with other names have been found, which may be customers of the works. Early bottles from the factory were squat and baggy, but by the 1750's they had acquired the shape closer to that of a modern sherry bottle.

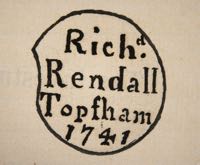

A fragment of bottle bearing the date 1741 and the name Richard Rendall, and one from 1793 with the name Richard Rundle which came from what was the pumping station at Newport near Countess Wear in July 1918 according to an Express and Echo article from the time. A print from June 1798 and engraved by J Hassell, F Dukes of Howland Street indicates, there were in total, three glass cones, although there is no other documentary evidence to back this up.

A furnace inside a cone would burn for many years and not be allowed to cool down; if it did cool down, the fire bricks would start to crack and fall apart, requiring the cone to be rebuilt. When in operation, it would burn at 1,250 degrees celsius, and require men to feed it with coal while the ashes and soot that would fall on them, had to be barrowed out.

One source suggests that an inhabitant from the

area in the 19th century stated that about 1820, the cone had been "thrown down

with wedges". This was a technique used to demolish a

building where it was underpinned with timber which was set alight,

collapsing the structure. In an earlier age, Cromwell had used sappers

to break down the walls of Corfe Castle with a similar technique.

The French prisoners

There is evidence to suggest that the glass house was closed for a few years from 1746 for the housing of French prisoners-of-war. Documents indicate that a Collector of Customs named Crew was directed by the Admiralty to adapt a house at the glasshouse to take the prisoners. In late 1746, 1,000 prisoners were held by Crew, but not all in the house as it was not complete. Admiralty records and some indirect supporting evidence confirm the change of use, and the eight acre site did contain a barn, stable, outhouses and two dwelling houses, as well as at least one large, brick cone. A glass cone at Stourbridge housed German prisoners during the First War and was also used as a canteen for children during the 1926 General Strike.

Sources: Devon and Cornwall Notes and Queries, French Prisoners of War by S Bhanji (Transactions of the Devonshire Association), website on the Red House cone at Stourbridge.

│ Top of Page │