The Goldsmith Arcade–J H Newman

Return to Retail Exeter

The first use of the term ‘hotel’ in this country was in 1769, when the now Royal Clarence Hotel opened for the first time as The Hotel. Within a few years, every self respecting inn became a hotel. The term arcade was somewhat similar. The first arcade in the country was the Burlington Arcade in London which opened in 1819. Arcades followed in Leeds, Cardiff, Cambridge and many other places. It became a fashionable place to go, so it was perhaps inevitable that Exeter would build the Eastgate Arcade in 1880.

The first use of the term ‘hotel’ in this country was in 1769, when the now Royal Clarence Hotel opened for the first time as The Hotel. Within a few years, every self respecting inn became a hotel. The term arcade was somewhat similar. The first arcade in the country was the Burlington Arcade in London which opened in 1819. Arcades followed in Leeds, Cardiff, Cambridge and many other places. It became a fashionable place to go, so it was perhaps inevitable that Exeter would build the Eastgate Arcade in 1880.

J H Newman

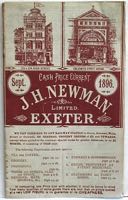

J H Newman first traded from 48 High Street from about 1872, moving to 213/214 High Street sometime later. Within a few years the company had expanded beyond tea to selling “many thousands of articles of every day use”. In 1887, Mr Newman decided that the ‘arcade’ experience would improve his business, no doubt because of the popularity of the Eastgate Arcade.

The shop at 213/214 High Street extended in depth, for about 150ft from the front facade. The opportunity to buy the premises in Goldsmith Street, adjoining the end of his shop must have come up in early 1887, because J G Stephens of Fore Street won the tender to construct the Goldsmith Street facade, and construct and fit out the length of the whole arcade. The architect and surveyor was Messrs Wilkinson and Warren.

Two grand entrances

The entrance from Goldsmith Street was an elegant design of Bath stone in a Classical style. The pediment and cornice were supported by simple Ionic columns, while each spandrel contained a figure carved by Mr E Roscoe Mullins from London–the figures represented the idealisation of tea and coffee, for Newman certainly had high ideals for his new retail space. For those, such as myself, who are not familiar with architectural terms, the grand entrance will be well known to many who remember the entrance to Waltons Supermarket in the 1960s.The High Street entrance was remodelled with a plate glass front, an expensive option that had recently become available from Pilkington.

The arcade was an L shape, 186ft in length from the High Street to Goldsmith Street, and covered an area of 3,106 sq ft. It was naturally lit from above by a partial glass roof, for which, the iron ribs were cast by the well known local firm of Garton and King. They also cast the wrought iron work of the gallery that ran around three sides of the glass roof at the Goldsmith Street end. Windows in the Goldsmith entrance were of stained glass from the craftsmen of F Drake, Cathedral Yard, while a line of gas lights down the centre of the arcade lit the space at night. A large basement was constructed for the storage of stock, with a floor of Exmouth bricks.

Arcade or not arcade

The new arcade opened in May 1888 with large adverts stating “The great providers for the million, from a prince to a peasant, the classes and the masses” and “walk through and see for yourselves.” I sometimes think that the promotional methods of Victorian entrepreneurs was as innovative then as those today. Mr Newman was keen to call his shop an arcade, but it was not like a traditional arcade, with different, independent shops along each side. Instead, stock was displayed along each side of the arcade, with counters and tills at regular intervals. It would have been an innovative concept at the time. Whether the arcade brought in extra customers is not known, for the use of the name ‘Goldsmith Arcade’ was quietly dropped in the mid 1890s, and the firm reverted to J H Newman, although its address was given as 213/214 High Street and Goldsmith Street Arcade.

The founder of the company, J H Newman retired to Western-Super-Mare, and died at the age of 69 on 20 December 1904, leaving an estate of £21,051 7s 1d. The firm continued to trade in the centre of the city until August 1925, when it was voluntarily wound up. The old Goldsmith Street end of the business was occupied by a jewellers for a time, before it was subsumed into Waltons, becoming a side entrance into the main store. When Marks and Spencer built their new store on the old Waltons site, they pledged that the would save some important architectural features in Goldsmith Street. The Goldsmith Arcade facade was demolished, a loss that should never have happened. Yet again, another example of commercial needs overriding our historic heritage.

Sources: British Newspaper Archive, material from Richard Holladay.

│ Top of Page │