The Cholera outbreak of 1832

Based on Thomas Shapter's book and with illustrations from John Gendall

Back to

historic

events in Exeter

Also see

Extracts

from Thomas Shapter's history from the Peninsula Medical School

It had been a fine summer when on the

19th July

1832, Dr Miller of the Exeter Infirmary attended a woman and her two

children in North Street, who had suddenly become sick. The woman, who

had recently come

from Plymouth, exhibited all the symptoms of a disease that the city

had long feared and expected, and within a few hours had gained the

dubious distinction of being the first victim of the cholera in Exeter,

a disease that was

sweeping through England. A second case of the cholera in a man

recently

arrived from London to St Thomas, was attended by Mr Woodman, a

physician from St Thomas and accompanied by a young doctor of the

name Thomas Shapter who was

also from the

Infirmary in Friernhay

Street. The man, who

exhibited all the classic symptoms of cholera recovered despite being

administered æether, ammonia and laudanum.

Exeter had been given plenty of notice that cholera was about, after

the disease visited St Petersburgh, Russia in the spring of 1831. The

first occurrence in England was in the Autumn of 1831 when it reached

Sunderland, and Exeter started to make preparations for dealing with

the disease, when and if it arrived. Curiously, just as some question

climate change today, there were voices opposed to taking action as

they were convinced that the whole epidemic was a figment of the

imagination, or worse still a conspiracy.

Even so, the city authorities, prompted by directions from Government, designed and printed special forms for recording cases on a day to day basis, made plans for the burial of victims and the disposal of infected clothing and bedlinen, formulated rules for isolating victims and protecting the healthy, and made a start on clearing and cleaning the most impoverished and filthy parts of the city that were thought to be most vulnerable. The Board of Health appointed four druggists, one for each quarter to assist the physicians, and in some cases attend cases. The druggist from the Exeter Dispensary, a Mr Hele, worked tirelessly, sometimes going out himself to bleed a patient.

The Board of Ordnance at the Higher Barracks had turned down a request to use the barracks as a cholera hospital, but they did issue specially marked blankets for use by the victims of the plague.

The disease takes hold

By the end of July, there had been 45 cases for the City of Exeter, of which, 19 had proved fatal. The 30th of July saw 7 deaths, the highest for the month. The city physicians, mostly working from the Exeter Dispensary in Friernhay Street attended the many cases that were occurring across the West Quarter and Exe Island. The bell of St Olaves was constantly tolling for the dead, and fear gripped the city.

Bishop Philpotts found it convenient to leave the city while the pestilence raged, much to the disgust of Thomas Latimer who wrote of his conduct in the Western Times. Ignorance did not help either, for many family and friends of the victims believed that the authorities were unduly hasty in dealing with the dead, and accused them of not affording respect, or worse still, of burying them alive.

On the 24th July, the

authorities hired 24 nurses, six per quarter to care for the increasing

numbers of sick. The physicians were exhausted from the high number of

cases they

had to attend and on the 16th of August, three resigned, forcing the

Board of Health to appoint three replacements, and welcome a volunteer

doctor.

The peak of the epidemic was August, with the 13th returning 89 new

cases and 31 dead. By the middle of the next month new cases were in

single figures, with the 13th September recording no deaths at all. The

last deaths occurred on the 20th October and the last two cases on the

27th October. In Exeter, there were almost 1,200 cases and 402 deaths

in total,

with St Thomas having 275 cases and 38 fatalities.

Disposal of the dead

The Board of Health devised a system of disposing of the bodies of the victims and their clothes and bedding that would have to be modified over time. Initially, bodies were wrapped in cotton or linen and doused in coal-tar or pitch before placing into a coffin. Each burial was in a pit 8ft deep and liberally sprinkled with quicklime. The first burials were in the Bartholomew burial ground, but within a few days the locals became increasingly fearful, and the burial yard became full. The last burial of a cholera victim in Bartholomews Yard took place in a full moon at midnight on the 16th August, and the gravediggers hauled the oldest tombstone in the burial yard, dating from 1637 over the new grave. Burials were made in other established burial grounds, the most notable being that belonging to the church of Holy Trinity, opposite Dean Clarke House, now a car-park.

However, unpleasant scenes and riots often occurred at the established burial yards, so attention was turned to creating a burial pit in Little Bury Meadow, but the locals attacked the grave-digger when he arrived to break the ground. In the middle of August another attempt was made to secure Bury Meadow, this time with more success and the land was consecrated for the first burials to proceed. By the end of August a second burial ground was opened on land to the west of Old Tiverton Road, close to Rowe's Barn Lane, belonging to Joseph Sparkes who had built Pennsylvania Terrace.

Even the collection of clothing could

result in

riot or disorder as

family and friends argued over the amount of compensation to be paid.

The disposal of clothing and bedding of the dead was arranged on a site

in the rackfields of Shilhay and a site in St Sidwells. Initially,

clothing was collected by 'inspectors' and burnt, but after a couple of weeks objections were raised by the

people of St Thomas because they thought the smoke was contaminated, so

burial in quicklime was introduced.

The Improvement Commission

The cholera epidemic had been a nasty jolt for what was a very conservative, and complacent City Chamber. Political reform was introduced across the country with the Reform Bill and Corporation Act, forcing city councils to provide clean water and sewage disposal paid for by household rates. Local measures were introduced and the Improvement Commission moved the livestock markets out of the city to Bonhay, and built the Higher and Lower Markets.

Once cholera had reached Exeter, it was spread through the population through water dipped from the leats of Shilhay. Evidence points to the Longbrook as the likely source of pollution, as effluent from North Street, the site of the first case flowed into the Longbrook and hence into both the Higher and Lower Leats. The water engine below Head Weir nor the Underground Passages were later found not to be responsible.

The water supply was improved by building a water works at Pynes and the polluted Longbrook and Chute Brook were culverted for storm water, while new sewers were built through the city. See Exeter's Water Supply

More on Dr Shapter

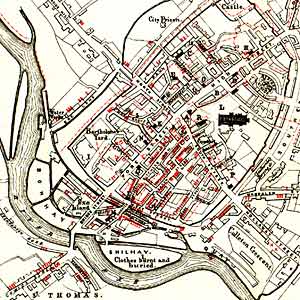

In 1848, Dr Thomas Shapter who had worked tirelessly tending the poor during the outbreak, was prompted by another visit of the cholera to Exeter, to document the 1832 epidemic. By referring to the surviving records, and by interviewing those involved, he produced The History of the Cholera in Exeter in 1832. Some of the unique features of the book were the many graphs and the detailed map showing the distribution of the epidemic by means of red marks representing single fatalities. The map illustrated very clearly, how the epidemic was concentrated on the West Quarter.

In 1854, another innovative physician, John Snow used Shapter's methods of analysis to pinpoint a particular water pump as a source of a cholera outbreak in London. From this work, it was discovered for the first time that water was the carrier of the disease, and led to the great Victorian program of sewer construction across all the large cities of the country. The statistical methods used by Shapter led to the modern science of Epidemiomology. In April 2007, Exeter's Peninsula Medical School announced the discovery of a 'fat' gene which is linked to rates of diabetes through the world, using the same statistical approach that Thomas Shapter used in 1848.

Sources - The History of the Cholera in Exeter in 1832 , Two Thousand Years in Exeter by W G Hoskins and Professor David Melzer of the Peninsula Medical School.

Part of the map printed in Thomas Shapter's book - the red marks

represent individual deaths.

Part of the map printed in Thomas Shapter's book - the red marks

represent individual deaths.

Poultry and pigs were kept in Rack Close Lane beneath the city wall.

Poultry and pigs were kept in Rack Close Lane beneath the city wall.

A riot at a cholera burial in the Southernhay or trinity burial yard,

opposite Dean Clarke House.

A riot at a cholera burial in the Southernhay or trinity burial yard,

opposite Dean Clarke House.

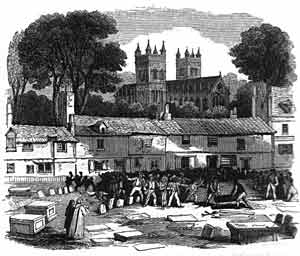

Burning bedding and clothes in the Shilhay rackfield. This was situated

on the future site of the house of Gabriel's Wharf. Notice

Colleton Crescent on the hill.

Burning bedding and clothes in the Shilhay rackfield. This was situated

on the future site of the house of Gabriel's Wharf. Notice

Colleton Crescent on the hill.

│ Top of Page │