The Salvation Army in Exeter

By Peter Hinchliffe

Page added 17th June 2011

List of other institutions or organisations

The Salvation Army started life as the East London Christian Mission in 1865. William Booth renamed his church “The Salvation Army” in 1878 and it soon spread out into the rest of Britain. From the very start they preached and held meetings on the highways and byways of the towns and cities, their brand of Christianity appealed to working classes with lively music, bands playing the latest Music Hall tunes, and religious words replacing the original. For the workers of that time there was little entertainment they could afford, it was either the pub, or go and join in with the “Sally Ann”, and that was free!

The Army was late in coming to Exeter. They were invited in 1881 by Mr Ernest Stear, a local Methodist preacher, who ran the Temperance Chapel in Friars Walk. He wrote to William Booth, the self styled General, and invited the Army to use the chapel. Booth readily accepted the offer and he selected a Plymouth Salvationist, Captain Abram Davey to “open fire” and attack the “Devil” and the “demon drink” in Exeter.

Early success

At the start they held meetings every evening and on Sundays. Even allowing for a little exaggeration, the first month was an amazing success. Davey, reporting to his superiors, claimed that on the first Sunday evening, the hall was full and 1000 people were locked out. He also claimed to have “saved 300 sinners”, men and women of the worst type in Exeter, he describes them as “drunks and Magdalens” (reformed prostitutes) who now attend fully clothed and in their right minds!

Captain Davey was soon a familiar figure in the City. At that time the West Quarter, (that area off Coombe Street and stretching down to the Quay and Exe Bridge) was a large festering slum, with hundreds packed into the dilapidated cottages and courtyards, and right on the doorstep of the Salvation Army Hall in Friars Walk.

Violent opposition

The Captain launched his attack on the pubs and drunks, of which the City had more than its share; when the publicans saw the crowds that the Army was attracting and keeping out of the pubs, they became alarmed, and with their profits diminishing, they would have to take action. In many parts of the country the brewers and publicans gathered a few roughs, supplied them with a “belly full of beer” and sent them out to disrupt the activities of the Salvation Army. These men were called the “Skeleton Army” and they turned out to the open air activities of the Army and fought with the people attending.

In Exeter the disturbances, although very frightening, were not as bad as other places, a woman Captain was killed whilst leading the open air service in Shoreham. Elsewhere two other Salvationists died from injuries received. The open air meetings in Exeter and those at the Temperance Chapel were attacked by “Skeletons” More frightening for the Captain and his family, was the harassment they suffered whilst making their way home to Portland Street, after the evening meetings

The Exeter City Police, like all the other police, had a novel way of dealing with the disorder caused. Instead of arresting the “Skeletons” who were the trouble makers, they arrested the Salvationists! Imagine today, that City life is disturbed by football hooligans, so the police go to St James park, arrest the manager and his professional football team, leaving the hooligans free to cause more disturbance!!

In August 1881 the local paper reported a week of nightly disturbances, and on one Tuesday the Captain was attacked outside the chapel in an incident described as “more violent than usual” and on another night a member of the Army was “knocked down and badly kicked” in Sidwell Street; he was detained in Hospital for several days.

There are reports that Captain Davey met the Watch Committee (responsible for policing) and he agreed to suspend the open air services, if the police would protect the hall where the meetings were held. That same evening a crowd of 1,000 gathered outside the hall, along with a strong force of constables to control them. The Captain stayed in the Friars that evening, but the Skeletons went to his house in Portland Street causing a disturbance and damage.

In October 1881 William Booth visited the City expressing his pleasure with the activities to date, rescuing men who had stood in the dock for the worst of crimes, saving “fallen women” and spreading the word amongst the people. He announced from the platform that they would buy the Temperance Chapel and convert it so that 2,000 people could be accommodated, and in the tradition of the Army (when using former chapels) it would now be known as Exeter Temple. He also presented a flag to them.

The Open Air activity started again, to be met with action from the Skeletons. They organised a flag presentation of their own, held on the Quay. Their leader “Figgy Martin” now called himself Major Martin, and he led his followers carrying a flag to the Temple, where there was a disturbance outside the hall, and all the windows smashed.

The City Council then wrote to Captain Davey telling him, that the Salvation Army processions were the cause of the troubles, and they would be stopped in the event of any further disturbance. After writing to General Booth, the Captain challenged the Council’s letter, and pointed out the entitlement of the Army to protection from the roughs and Skeletons.

In November, in an unusual move, The Salvation Army applied to the City Magistrates to swear in 16 of their members as Special Constables, deemed necessary to protect people entering and leaving the Temple. The Magistrates refused the application

Captain Davey was promoted to Major and moved out of the City. On his retirement, he returned with his family, his son opened Davey’s Cycles, in Cowick Street, his daughter Ellen became Ellen Tinkham, founding the school now named after her.

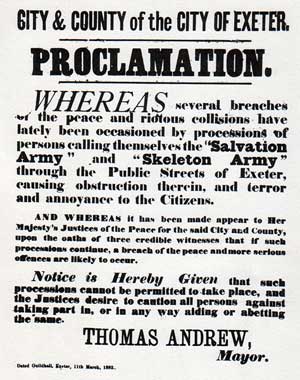

The Mayor's Proclamation

His replacement, Captain John Trenhail, took up the open air activities with renewed vigour and was equally opposed by the Skeleton Army. The disturbances grew in number and ferocity. In 1881, the Mayor of Exeter Thomas Andrew (a publican) issued a proclamation which prohibited both the Salvation Army and their opponents The Skeleton Army from marching in the streets.

This proclamation was completely without legal foundation, and was, much later roundly condemned by the Lord Chief Justice of England.

The Sunday after the proclamation was issued, Captain Trenhail tried to test the resolve of the authorities; in the morning several separate open air meetings were held, and the Salvationists walked back to the Temple in small groups. The police attended these meetings and would not allow the Salvationists to sing hymns, and they “moved them on”

Emboldened by the morning events, a bigger open air meeting was held in Cowick Street. A drunken man attacked the Captain and knocked him to the ground. The meeting was abandoned and the Army started to walk back to the Temple, pursued by ruffians. Near St Thomas station they were met by the Skeleton Army marching toward them, fisticuffs occurred, including Salvationists being hit with sticks. (St Thomas was then not part of the City) The City Police waited for the procession to cross the Bridge, and then escorted it.

The crowd became too great for the available police to control, so the Captain and a few followers escaped through an alleyway called John Street, whilst the police stopped the mob entering the alley.

The first arrest

As he returned to the Temple the Captain started to sing a hymn, he was warned to stop, or face arrest. He continued singing and was marched off under arrest to the Guildhall, where he was thrown in the cells

After conducting the afternoon meeting the Captain’s wife went to the Guildhall with some tea and a blanket for her husband, but she was turned away, and not allowed to see him.

At this time the Salvation Army throughout the country were vigorously defending the arrest of their members for “proclaiming the gospel” Employing leading QCs, even at Magistrates Courts, whilst reaping the publicity of the arrests. The Salvationists refused to pay any fines, gaining more publicity from the prison sentence. The man or woman arrested would have been escorted to the Prison on foot, with the Salvation Army band in attendance supported by others. On release there would have been a even bigger demonstration of support, with the prisoner led back in triumph to the Salvation Hall for a service of thanksgiving.

When Captain Trenhail appeared before the City Magistrates, he was defended by Mr Simon Reeve, an eminent QC of the South Eastern Circuit (sent from London by General Booth) whose eloquence lead to a strange conclusion. The Magistrates did not find the Captain guilty of any offence, and saw no reason to bind him over. He recommenced open air activities and the marches back to the Temple, the following week.

Space in the Temple in Friars Walk was limited and people were turned away from meetings because the “House was Full” so it became necessary to open further premises in Cricklepit Street, and further premises in Friernhay Street, which became known as the “Fort” or formally as Exeter2. It was a subsidiary of the Temple.

From the start there was a problem with the neighbours, who objected to the noise and music. It was brought to a head on Sunday 29th., January, 1882. The mayor himself attended to assess the complaints, he agreed with the residents and directed that the Army should not march in the very narrow Friernhay Street. Captain Simpson now in charge of the Army would not comply with request, and was arrested by the Police along with two of his soldiers.

The following day they appeared before the Magistrates at the Guildhall. By now of course they were legally represented. Their solicitor applied for summons against the policemen! The Mayor gave evidence and two Salvationists were found guilty of an assault on the police. One was 16 year old Fred Woolway who was fined £2 or one months hard labour, and the other man Henry Gillard was given three months hard labour without the option of a fine; both men were placed in manacles and marched off to Exeter Prison, accompanied by the band and many Salvationists.

Henry Gillard was a recent convert, a man with a long criminal record, who had undergone a transformation since joining the Army. He was never in trouble after he joined, apart from playing the drum for the Salvation Army!

That evening Major Davey, now in charge of the Army in Devon & Cornwall came to Exeter to lead a meeting at the Temple to consider the situation and the plight of the two Salvationists, locked up at the prison. Davey by this time had personal knowledge of “hard Labour”, having been arrested for playing the concertina in Penzance, and serving two months!

At the conclusion of the meeting that evening, the entire congregation, led by the band, marched to Exeter Prison where they paid the fine for Fred Woolway to be released immediately. Later Major Davey persuaded the Mayor to release Gillard in return for an agreement that the Army would stop marching in Friernhay Street.

Victory of a sorts

In 1882 the Salvation Army achieved victory in the Queens Bench Division of the High Court, in a “stated case” (Gillbanks v Beatty). The Lord Chief Justice of England, Lord Coleridge (of Ottery St Mary) ruled that the Army had a right to march anywhere, at any time, and be protected whilst doing so. He was also critical of the Exeter Mayors Proclamation, which he described as without legal foundation. This was almost the end of problems with the authorities and the Skeleton Army in Exeter.

The same week as the momentous court decision, the Salvation Army were marching in Sidwell Street, when the Colour Sergeant was attacked by roughs, the flag was damaged and blood stained in its defence. The flag is on display at the Temple to this day.

It is difficult now to fully understand why the Court rulings on the Salvation Army were not applied throughout the land but they were not.

Support for Crediton and Honiton

There were still similar problems with the Skeleton Army at Crediton,and a total of 82 members of the Army in Exeter went to Crediton to support their colleagues. Eventually several members of the Army were arrested including the female Lieutenant Saville of Exeter. They appeared before Crediton Magistrates, were fined, refused to pay and were sent by train to Exeter Prison. They were met at Exeter St David's station by Captain Trenhail and the band, As they were marched up from St David's in handcuffs, the band played “Anywhere with Jesus I will go”

In 1883 the Honiton Corps of the Army was still being harassed by the Skeletons. It seems that following one attack, the Army Captain was arrested for retaliation when he kicked one of the attackers. For this assault on his tormentor the Captain was fined, given time to pay, but he refused to pay.

On the day that the fine became due, the Exeter Temple Band went to Honiton in support of the Captain, and to accompany him back to Exeter Prison, where he was to serve one month on failure to pay. He was duly imprisoned, handcuffed, and sent on the train to Exeter Prison.

The authorities at Honiton decided that they would not let the Band travel back to Exeter on the same train as the Captain, who was now a prisoner serving his time. Stranded at Honiton overnight, the band came back to Exeter by the early morning train, and then paraded through the streets back to the Temple!

This marked the end of problems with the police in Exeter, General Booth visited Exeter at the end of 1884 and reported that more than 600 Salvationists had served prison sentences in England that year.

Whilst the difficulties in Exeter had subsided there were still problems elsewhere, and the Salvation army sought volunteers to go to these towns so they could be arrested, the idea being to fill the prisons, and ridicule the system! The Salvationists always refused to pay any fines imposed, choosing instead the option to go to prison.

Exeter Salvationists went to Torquay where the council consisted of men in the hotel trades. Under an obscure act relating to the harbour and navigation, they were able to “outlaw” the Salvation Army, for holding open air meetings around the Harbour. General Booth sent his daughter Evangeline to Torquay to assist the local Captain.

Fred Woolway was again arrested in Torquay, as was becoming what is now termed a recidivist, always in trouble with the police! Eva Booth was convicted and served time in Exeter Prison. On her release she was met by the Exeter Salvation Army band and led in her convict’s uniform to the Temple, where she conducted services that lasted until midnight.

The Citadel

The Temperance Chapel or Hall was extended to its present form, providing seating for 2000, and ancillary rooms. The front of the building in Friars Gate was built as a “citadel” with its tessellated features, the revised building being opened by Mrs Bramwell Booth the daughter in law of the General.

By the turn of the century the Salvation Army came to be accepted by the local authorities in Exeter, and by the established churches. This was the time in the City that the Army branched out into its Social involvement. The Army were feeding 200 children from the West Quarter daily, giving each a cup of cocoa and a bun spread with butter and jam for a farthing, if they could afford it. Those who could not were fed anyway. Children attending the breakfast were “inspected” and provided with other requirements where necessary, such as clothes, boots and shoes. A soup kitchen was also established for the needy adults.

These additional services provided by the Army led to the establishment of a Goodwill Centre, in West Street, which finally closed its doors in 1949. The centre was dispensing aid to the poor and needy of the area, including coal in the winter months.

A helping hand for the troops

The First World war saw the arrival in Exeter of many men volunteering (or conscripted) in to the British Army, many received their training at the two barracks in the City; the Salvation Army was busy providing welfare services for these young men, away from home for the first time. The band led the march from Topsham Barracks to the Cathedral every Sunday morning for the military church parade the men had to attend.

Until well into the First World War, the British Army insisted on paying the soldiers in the Trenches in cash. If the man wished to send money to support his family back in Exeter he had little choice, he could use the Post Office, but that was not possible on the Front Line. The Salvation Army had men (later women, when their men were removed as Conscientious Objectors) in the Trenches supporting the combatants, who would take the money in exchange for tokens, which could be sent home to the family for encashment at the Temple, or other Salvation army hall.

Several Military Hospitals were established in the City, to treat casualties from the War, the band was visiting these to entertain the wounded men, giving support and comfort where ever they could.

The Salvation Army has always had a reputation for dispensing tea and sandwiches to anyone that needed them, but during the War, even they reported difficulty getting sufficient supplies because of the rationing of food stuffs.

The Salvation Army continued to hold it’s open air meetings on street corners and other convenient spots. To this very day they observe the lawful requirements of the 1882 case, which says they have the right to march, but they have no right to stand still. Every open air meeting is held in the formation of a circle, a policeman can insist that they “march”; in which case the musicians and singers could walk around in a circle, playing, singing, or praying, and would be protected by the law.

It is said that the patrolling policemen used to make them “go round in circles” until after the First World War. Then many of the police had served in the Trenches and had benefited from the welfare activities of the Salvation Army, so the constable would go the other way on his beat, leaving the Army well alone.

The Exeter Salvationists were busy supporting the local community through the lean years after the First World War, their history shows difficult times, when raising funds to do their charitable work, there never seemed a shortage of people in need.

The growing support and attendances required further premises. Another Hall (or Corps) was started in Blackboy Road next to Belmont Park, in a building called Belmont Hall, it appears to have closed in the mid 1920s. Another Corps was started in St Thomas at first in premises in Alphington Street, but later in a hall beside the old County Ground Stadium. Many older folk will remember the St Thomas Band entertaining the queues for the Speedway and Rugby fixtures. There was also an ”Outpost” opened in Burnthouse Lane, the estate built to accommodate the slum clearance of the West Quarter. By the 1970s the only building left was the Temple in Friars Gate.

Coping with the blitz

The Second World War brought conflict to the streets of Exeter. The mobile canteens of the Salvation Army were a frequent sight, providing refreshment to the troops and the ARP workers as they toiled with the blitz.

This war brought several American Salvationists amongst the Military personnel. In the war the American authorities imposed a “colour bar”. Troops of negro descent were not allowed into the City, they were restricted to St Thomas. Many joined with the corps in Church Road, but they were not allowed to attend at the Temple!

In more recent times the Salvation Army were present dispensing aid, assistance and comfort in times of emergency. They were prominent in both the Floods of 1960 and the evacuation of the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital during the major fire.

Until the 1960s the Salvation Army held at least two open air services in High Street each Sunday afternoon, one opposite Boots Shop or in Castle Street, and the other in Goldsmith Street, at their conclusion both bands accompanied by about 100 followers, would march back to the Temple.

The band are a regular sight in the streets at Christmas time, playing carols for the crowds of shoppers, raising money which they use to dispense cheer to the needy. On Christmas Day they hold a Festive lunch at the Temple, where they invite anyone who is alone, or in need, to join them.

Sources: With thanks to Ruth Hawker for her invaluable help.

Click photos to enlarge Mayor Andrew's Proclamation of 1882

Mayor Andrew's Proclamation of 1882  Map showing Fraternhay and John Streets, scenes of many disturbances with the police.

Map showing Fraternhay and John Streets, scenes of many disturbances with the police.  The Exeter Corps flag.

The Exeter Corps flag.  The Citadel before the castle like crenellations were removed.

The Citadel before the castle like crenellations were removed.

The band marching troops along Holloway Street from the Topsham Barracks - a task undertaken every Sunday during the First War.

The band marching troops along Holloway Street from the Topsham Barracks - a task undertaken every Sunday during the First War.

The band playing to patients at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital.

The band playing to patients at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital.

│ Top of Page │