Gallows Cross - Heavitree

Devon's place for executions until 1795

Page updated 27th July 2015

Back to Places of Exeter

Also see Executed of Exeter - a full list of known executions.

Livery Dole was the original place of execution, for both Exeter and Devon. When Exeter was granted city status, in 1537, the County of Devon opened a new place of execution at the apex of the junction between the Honiton and Sidmouth Roads – it became known as Gallows Cross. It was also referred to as Ringswell and the Heavitree Drop. The actual place of the drop is just to the east of the traffic island which divides the Honiton and Sidmouth Roads.

The earliest recorded execution at Ringswell was John Waltheman in 1532. He was convicted of treason. The Rev Oliver wrote "John Waltheman was executed as a traitor at Ringswell, who being given to blind prophesying did interpret and apply them to the King." He was hanged, drawn and quartered at 'Ryngeswell'.

Joan Tuckfield, widow of John Tuckfield, mayor in 1549, gave in her will to the Corporation of Tailors a piece of land next to the drop, for the burial of the executed. "and also keep in constant repair the walls, or inclosure, doors, and locks of a piece of ground appropriated, at her expence, to the burial of malefactors executed at the adjoining gallows, at Rings-well, near Exeter: previous to this they were interred in the common highway.)" Not all were buried in the small yard, for before 1832, relatives could claim the body of a person who was not convicted of murder. Many were interred at St Sidwell's.

Griffith Ameredith, Sheriff of the city in 1555 also left funds for the maintenance of the burial ground; in addition, funds were left for purchasing shrouds, at a cost of 3s 6d each, for the condemned prisoners. The cemetery was consecrated by Bishop Turbeville in 1557, and desecrated in 1827.

The condemned were transported by cart to the gallows. Andrew Brice wrote in the Mobiad in 1770 "The Burial-Yard of Heavitree-Gallows belongs to our Company of Taylors to take care of, for which a Bit of Land was bequeath'd to 'em. Once a Year they walk out in a Body to visit it, when on the Bridge, at a Place call'd Iron-Dish they tarry some Time, treating each Passerby with a Mug of Ale." For the condemned, Heavitree Bridge was used as a resting place, where the prisoners could have a drink of water.

Notable executions

Here also were hanged William Horsington, Thomas Hylleard, Thomas Poulton, Richard Reeves, Edward Davy, Edward Willis, and John Giles (alias Hobbes). They were all buried in St. Sidwell's churchyard on the seventh of May, 1655. They were convicted of being involved in an uprising in 1654-5, along with Capt. Hugh Grove and Col. John Penruddock who were beheaded at the Castle. Richard Wilkins, was executed for witchcraft, at Ringswell, in July, 1610. He was buried at St. Sidwell's.

Females who were convicted of murder with poison were condemned death by burning at the stake. In 1750, Elizabeth Packard suffered this fate for poisoning her husband. Possibly the most famous female to be burnt at the stake at Heavitree was Rebecca Downing in 1782.

The last execution to take place at Heavitree Gallows was Joan Stone in 1794. "Friday last was executed at Heavitree Gallows, pursuant to her sentence, Joan Stone, for setting fire to her Master's dwelling house and barn, by which both were consumed. She was but 17 years of age."

The modern Gallows site

The gallows were retired and public executions moved to the newly built Exeter Prison. During the 19th Century, when the judge for the Devon Assizes travelled to the city, he would be met by the High Sheriff and 'javelin men' at Gallows Corner. The Sheriffs Trumpeter would "blow an honourable blast' of greeting. Once the formalities were over, the judge would enter the Sheriffs carriage to be escorted to the Guildhall. At the corner locals, including farmers would gather to watch the spectacle, and admire the horses and coach. The last time this ceremony was recorded by the local newspapers was for the March 1850 Assizes– after that date, the Assize judge would arrive by train.

Gradually, the grisly Y junction's use as a gallows faded from memory.

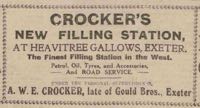

With the rise of the motor car, the junction was thought ideal for a filling station. Mr A W E Crocker, decided to open a filling station at Heavitree Cross in the autumn of 1926. During the excavation of the site to sink the petrol tanks, in the September, human remains were found in the garden of the cottage at the apex of the junction. Initial discoveries included skulls, a jawbone, and a thighbone. Within weeks the bones of at least 20 individuals were found. The Home Office was contacted, who granted permission for the remains to be placed in a box and be re-interred. Photographs were taken, which were passed around a meeting of the Council. On 5 October, the remains were buried at Topsham Cemetery.

With the rise of the motor car, the junction was thought ideal for a filling station. Mr A W E Crocker, decided to open a filling station at Heavitree Cross in the autumn of 1926. During the excavation of the site to sink the petrol tanks, in the September, human remains were found in the garden of the cottage at the apex of the junction. Initial discoveries included skulls, a jawbone, and a thighbone. Within weeks the bones of at least 20 individuals were found. The Home Office was contacted, who granted permission for the remains to be placed in a box and be re-interred. Photographs were taken, which were passed around a meeting of the Council. On 5 October, the remains were buried at Topsham Cemetery.

The filling station was constructed, once the remains were removed. An incident, involving the filling station, in June 1928, illustrates the pioneering days of aviation. Captain Phillips of the Cornwall Aviation Company was flying from Winchester to Cornwall when he decided to land next to the Heavitree Gallows filling station to top up with petrol. He descended to land in a field, but as he touched down he discovered that the grass was longer than it was safe to land. He immediately pulled the aircraft up, to find another field, when the aircraft pitched forward and the propeller was smashed on the ground. Phillips was not hurt–a RAC patrolman who was on duty at Gallows Corner rendered assistance. The filling station was listed as 'damaged' in an air raid of the 6 May 1941.

What was a significant place in Exeter for doling out the judgment of the law is now a busy junction. Many who pass this way on their way to work in the city probably never have a thought for the grisly scene that took place two or three times a year before 1795.

Sources: Exeter Flying Post, Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, Rev Oliver's History of Exeter and Worthy's History of the Suburbs of Exeter.

The filling station. The tower is in the approximate position of the gallows tree. Note that the sign below the tower reads Carburine, a petrol brand of the time. © Bertram Arden.

Another view of the bones–they did not treat the remains with the same respect that a modern excavation would give. © Bertram Arden.

│ Top of Page │