Lazy Landlord – Bonhay Road

Also known as the Princess Alexandra

Including the infamous Annie Tooke 'baby farmer' case

Page Added 25th September 2016

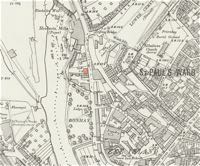

In 1863, Bonhay Road was opened as far as St David’s Station. Now a through road, traffic increased from the junction with Bridge Street, and the cattle market, to the station. It was inevitable that someone would open a beer house, with accommodation, in the road, to catch passing trade to and from the cattle market. In September 1863, Daniel Hooper applied for a spirit license for the Princess Alexandra beer shop. The application was opposed by the local church wardens, and despite the provision of accommodation for travellers, horses and carts, passing along Bonhay Road, it was turned down.

In 1863, Bonhay Road was opened as far as St David’s Station. Now a through road, traffic increased from the junction with Bridge Street, and the cattle market, to the station. It was inevitable that someone would open a beer house, with accommodation, in the road, to catch passing trade to and from the cattle market. In September 1863, Daniel Hooper applied for a spirit license for the Princess Alexandra beer shop. The application was opposed by the local church wardens, and despite the provision of accommodation for travellers, horses and carts, passing along Bonhay Road, it was turned down.

Despite the refusal, the house was still able to serve beer and cider, along with providing accommodation. The spirit license was eventually granted in September 1864. The inn was named after Princess Alexandra of Denmark who married the Prince of Wales in 1863.

Powhays Mill was just opposite, so the house was the obvious choice for a celebratory dinner in April 1872, for the so called ‘short time movement.’ Millers in the city had been lobbying the mill owners to reduce their hours by an hour and a half. The master millers had granted the shorter week, hence the dinner at the Princess Alexandra.

Many drownings, many inquests

Landlord Mitchelmore’s house was used for many inquests; a case in February 1872 was the death of a 2½ year boy named William Dymond who was burnt to death in his cot. He was being cared for by a nurse, while his mother was working for a butcher. The child had knocked a candle over and set light to his night dress. A verdict of accidental death was given.

In the July of the same year, the body of a newly born boy was found, wrapped up in a cloth and brown paper, tied with a cord, trapped in the grate of the leat at Powhays Mill. An open verdict was passed. Another inquest at the Princess Alexandra in January 1873 covers a double drowning in the leat. The body of Hannah Stone aged 32, a mother of three children was found in the leat by the mill. She had been suffering head pains; her husband returned to the house to find she had gone with her youngest child, aged six months. The leat was drained at Powhays, and the body of the baby was found. A second inquest was held for the baby, at the Princess Alexandra, where the coroner stated “That the child was found drowned, but how or by what means it came in the water there was no evidence to show.”

There were several other inquest at the Princess Alexandra into the death of children, but the finding of the body of Reginald Hyde in 1879 would lead to the most infamous case of all.

The ‘baby farmer’ case

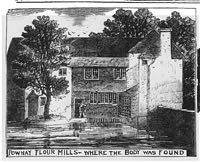

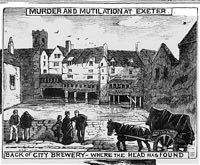

On Saturday 17 May 1879, the torso of a six month old boy was found in the leat grate at Edmund Brown's Powhay Flour Mills by Edward Stokes, a miller. The child's head, was later found further down the leat at Horse Pool, while a hand and leg were found near the Round Tree Inn, at the rear of the City Brewery. Other parts were found in the leat at the Shakespeare Inn by a young boy. All the body parts were taken to the Princess Alexandra Inn, where the surgeon was called and the parts reassembled (sewn back together). The coroner Mr H W Hooper held the inquest at the Princess Alexandra on the afternoon of the discovery. The surgeon gave evidence that the child was about six months old and well nourished. It was found that the arms and legs had been neatly cut below the elbows and knees, perhaps with a small saw. Because of the complexities of the case, the inquest was adjourned for a week.

The nature of the case was soon public knowledge, and the proceedings reported across the nation–there was barely a newspaper that did not have a report, often lifted directly from the Exeter papers. The police investigated and found the mother, Mary Hoskins, who was charged with being an accessory to murder. At the inquest a week later, at the Guildhall, it transpired that Hoskins, from Cornwall, had been living in Ide for a few months, when she gave birth to a boy. A few weeks later, one Sunday in November 1878, Hoskin's relatives visited her, and she, the child and her relatives left Ide for Exeter. Hoskins looked for someone to 'farm' the baby out to, finding Annie Tooke, a nurse with several children, who lived in South Street. When cross examined, Tooke said that Hoskins had given the baby to her to look after for an advanced payment of £12. On the 12 May the next year she said that a young women she did not know, came to fetch the child for his mother. This was five days before the remains were found. The police decided to investigate Tooke and two days after this evidence was given, Tooke was arrested for the wilful murder of the baby. As she was led away from her home she is said to have remarked “I suppose they will say that they have got me this time.”

Mary Hoskins was acquitted; there is some speculation that she was forced to give the baby to Tooke, a so called ‘baby farmer’, by her family because the father was her brother. The trial continued, and evidence was found in a box at Tooke's lodgings of a hammer, a petticoat and other items covered with traces of blood. There was now sufficient evidence to send the case to the assizes for trial.

The trial ran for two days from 21 July. The jury deliberated for an hour and ten minutes to return with a guilty verdict, and the judge sentenced Tooke to death. Tooke was asked if she had anything to say and replied “I wish to say that Capt. Bent (Exeter’s police chief) has sworn false against me.” She then said “I wish to thank my able counsel for what has been done for me.” Tooke was taken to the County Gaol, and was executed on 11 August 1879. Before her death she signed a confession for the murder.

“I hereby acknowledge that the confession which I first made to Capt. Bent is true in the main particular, and that I am justly to suffer for my dreadful crime for which—as for all my many sins—I do most truly repent, and humbly pray God’s mercy for the sake of His dear Son my only Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ.

Signed by me, ANNIE TOOKE, this day of August 1879.

Witness S. A. Hugos, Matron.

Sutton Kirkpatrick, Governor of

H.M. Prison at Exeter.”

Life goes on at the inn

By 1884 the inn was run by Mr Taylor, when he had his license renewed. He died in 1890 and the license passed to his wife. In 1907, Fred Parsons, the five year old son of the landlord, was tossed into the air by an escaped bullock. The boy was treated for his injuries.

In June 1920, a char-a-banc outing from the Princess Alexandra to Plymouth, ended in disaster on Dunsford Hill. A party of thirty were on board, when the brakes failed, on a hill, and the machine ran into a telegraph pole. Ben Shaw was thrown out and killed, while seventeen others were taken to hospital by St John’s Ambulance. One of the injured, William Coombe, 77 years old, licensee of the Princess Alexandra Inn, died two months later due to his injuries. A third person also died in the crash.

The Princess Alexandra Inn was taken over by Austin Outside Caterers when they moved from their Bartholomew Street base in 1969. The move gave them a license to sell alcohol which they could use for outside catering events. It was closed by the brewery in May 1982 before re-opening as the Lazy Landlord. In 2000 the Lazy Landlord was finally closed, and in 2002 demolished and replaced with apartments.

Sources: The British Newspaper Archive (Western Times, Exeter and Plymouth Gazette and Flying Post). Richard Holladay.

│ Top of Page │