- Home

- Memories

- Scrapbook ▽

- Topics ▽

- People ▽

- Events

- Photos

- Site Map

- Timeline

Page updated 24th January 2013

Return to Industrial Exeter

Also see Celia Fiennes writes about the wool trade

It is one industry above all others, that Exeter can thank for its prosperity from the 16th through to the 18th Century - that of processing and exporting woollen cloth.

The nature of the land in the south west lends itself well to sheep farming. The flocks were scattered across many small family run farms, combining sheep farming with general agriculture. The production of woollen cloth, initially kersey, and from the early 17th Century, serge, was also on a family basis - the carding and spinning undertaken by the wife, children and family servants of the household.

Hooker wrote of wool at the time "the best commodity that this country doth yield and which keepeth most part of the people in work".

The sale and purchase of fleece and cloth took place in the local markets of Moretonhampstead, Crediton, and other country towns. Exeter was the centre for all this commerce.

Kersey was introduced in the fifteenth century and by 1600, its production had made Devon one of England’s leading textile areas. It was made from lower grade wool, using both long and short fibres, giving a coarse finish to the cloth. It was used to make clothing for servants and the poor. Kersey was woven in a twill structure, so a diagonal rib ran across the surface of the cloth. The sample coloured orange, right, has been woven with a combination of the course Devon longwool and the softer Leicester longwool. This sample of yarn was dyed with the root of the madder plant, colouring it orange.

It was about 1615 that a finer cloth, known as serge, was introduced. It fast became the main product of Exeter's fulling mills, and by 1700, 1,200 weavers were employed across the county.

Serge is a cloth that is best suited to wool that was available from Devon and Somerset. It was made from a combination of long fibre wool that traditionally produced worsted, and woollen yarn which is made from a shorter and softer fleece. The surface of serge is diagonally ribbed from its twill structure, giving a front and back. A form of serge was later developed that only used woosted wool for the ubiquitous suit, that we are all now familiar with.

After the Civil War the woollen merchants of Exeter controlled the whole process; they purchased the fleece at the local markets, sent it for carding and combing, and had it spun into yarn. The yarn was then woven into cloth before it was transported to Exeter on pack animals for finishing at the fulling mills.

The merchants were freemen who belonged to the Guild of the Fullers and Tuckers. Guild members in the 18th century were known as the 'Golden Tuckers' because their wealth allowed them to clear the market of the most expensive items. They were also noted for their green baize aprons with red strings. The Guild originally met on the premises of the Bishop Blaize pub, but in 1471 they built Tuckers Hall in Fore Street. It is still used by the Guild of Weavers, Tuckers and Shearers. They were a powerful elite in the city and many of the 24 members of the City Chamber, the equivalent of our City Council, were Guild members. Almost half of those admitted as freemen into the guilds in the 16th Century were engaged in one aspect or other of the cloth industry.

Exeter was the centre for the woollen trade in the south west and at its height, had at least three purpose built cloth markets in the city. The first market was opened in 1538 by Henry Hamlyn, the Mayor who established a weekly market for wool, yarn and kersey. Stone from St Nicholas Priory was used to build the market over the old Shambles in South-gate Street. (taken down circa 1720) In 1542 a new establishment, close to Hamlyn's market for raw cloths and yarn was opened Wednesdays and Fridays (market days) in a new building over and against St George's Church, in the Shambles.

The New Inn, next to St Stephens Church was established, as a market hall, in 1555 when the City leased the building from the dean and chapter for a "common hall for all maner of clothe lynnen or wollyn and for all other merchandise and which shalbe called the merchauntes hall".

The last of the markets was opened in April 1636, due to the New Inn suffering from overcrowding. New quarters were found, and regulations agreed, for the wool market in the lower hall of St John's Hospital School.

Other premises were also used for buying and selling wool and woollen goods including the Guildhall, in 1533, for foreigners to trade in linen and cloth (foreigners were anyone who was not an Exeter merchant), and a market was held in North-Gate Street for a time. However, by 1640, St George's, the New Inn and St John's were the markets engaged in buying and selling woollen products. Other markets were established on market days across the city for other commodities.

Jenkins wrote in 1805 that:

"the open street, before the Bear Inn, is weekly held, on Market Fridays, the Serge Market, formerly much noticed, and supposed to have been the largest in this kingdom, except that of Leeds, in Yorkshire; but it has, from various causes, greatly declined of late years".

Exeter produced cloth that was processed in the fulling mills of Exe Island from as early as the 13th Century. Much of this cloth was for the home market, with some exports. Much of the rest of England's wool exports were unfinished yarn to the Royal monopoly at Calais, where it was woven into cloth in France and the Low Countries. After the capture of Calais in 1558, the weaving industry expanded as skilled Calvinist serge weavers were driven out of the Low Countries by the Eighty Years War and settled in Exeter and Devon.

Exeter's woollen industry flourished and woollen products were exported to France, and Spain. After the Civil War, the Merchant Adventurer Company in London and the Exeter French Company lost control of the export trade and individual merchants started to export their own cloth and import other goods. In addition, a depression in trade after 1660 and after the French imposed fierce tariffs in 1667, the newly free merchants were forced to find new markets, especially in Holland. The exact export market would vary from year to year, dependent on which country England was at war with at the time, but the Dutch remained the main market until the end of the 18th century.

The export of woollen goods supported the ports of Topsham and Exeter, and allowed the merchants' ships to return with a variety of imports including wine from Bordeaux and the Canaries, canvas and linen from Normandy, and increasingly, tiles and bricks from Holland. The flocks of Devon sheep could not keep up with serge production, and fleece had to be imported from the surrounding counties and Wales, and eventually imports of raw wool from Ireland and Spain dominated the supply of raw material for weaving the cloth.

The finishing of the cloth was centralised at Exeter - the abundance of water power in a small area allowed the mills to finish the cloth, ready for export. Before fulling the cloth was soaked in stale human urine, which contains ammonia and fuller’s earth to aid the process. This process would cleanse the wool of oils, dirt and other impurities and thicken the fibres by matting the surface texture. Every night, urine was collected from taverns, inns and houses by men from the 'piss cart'. The wool was pummelled with large square wooden hammers, or fulling stocks, tripped by wooden cams, directly driven by the water wheel. Celia Fiennes gave a very thorough description of the process:

"The carryers... with their loaded horses, they bring them all just from the loom and so they are put into the fulling-mills, but first they will clean and scour their rooms with them - which by the way gives no pleasing perfume to a room, the oil and grease, and I should think it would rather foul a room than cleanse it because of the oil - but I perceive its otherwise esteemed by them, which will send to their acquaintances that are tuckers' the days the serges comes in for a roll to clean their house, this I was an eye witness of, then they lay them in soak in urine then they soap them and so put them into the fulling-mills and so work them in the mills dry till they are thick enough, then they turn water into them and so scour them; the mill does draw out and gather in the serges, its a pretty diversion to see it, a sort of huge notched timbers like great teeth, one would think it should injure the serges but it does not, the mills draws in with such a great violence that if one stands near it, and it catch a bit of your garments it would be ready to draw in the person even in a trice; when they are thus scoured they dry them in racks strained out, which are as thick set one by another as will permit the dresser to pass between, and huge large fields occupied this way almost all round the town which is to the river side; then when dry they burl them picking out all knots, then fold them with a paper between every fold and so set them on an iron plate and screw down the press on them, which has another iron plate on the top under which is a furnace of fire of coals, this is the hot press; then they fold them exceeding exact and then press them in a cold press;"

The serge was thoroughly washed in river water to prevent it shrinking, and then dyed in the dying houses, as Celia Fiennes explained:

"I saw the several vats they were a dying in, of black, yellow, blue, and green - which two last colours are dipped in the same vat, that which makes it differ is what they were dipped in before, which makes them either green or blue; they hang the serges on a great beam or great pole on the top of the vat and so keep turning it from one to another, as one turns it off into the vat the other rolls it out of it, so they do it backwards and forwards till its tinged deep enough of the colour; their furnace that keeps their dye pans boiling is all under that room, made of coal fires; there was in a room by it self a vat for the scarlet, that being a very chargeable dye no waste must be allowed in that; indeed I think they make as fine a colour as their Bow dyes are in London; these rollers I spoke off; two men do continually roll on and off the pieces of serges till dipped enough, the length of these pieces are or should hold out 26 yards."

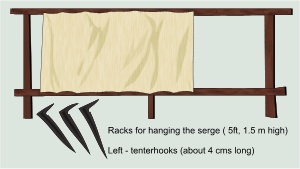

The serge was hung on racks in large wooden drying sheds, and more usually, in dry weather, rack fields. The phrase, 'being on tenterhooks' comes from hanging the cloth on frames called tenters, using tenterhooks. The rackfields were also known as the tenterground. Much of Exe Island around the site of the old cattle market, the area now in front of Renslade House, Shilhay, Friernhay where Colleton Crescent is situated, and parts of St Thomas were given over to the rack fields.

Sources: Izacke's Remarkable Antiquities of the City of Exeter, Jenkin's Civil and Ecclesiastical History of the City of Exeter, Exeter 1540-1640 by Wallace MacCaffrey, Seventeenth-Century Exeter by W B Stevens.

Tuckers Hall in Fore Street. Photo by David Cornforth

Tuckers Hall in Fore Street. Photo by David Cornforth  St John's Hospital School was located where the Virgin Record Store is now.

St John's Hospital School was located where the Virgin Record Store is now.  Kersey on the left and serge on the right.

The diagonal twill on the right is formed by the weft going over two and then under two of the warp yarns. Swatches from Coldharbour Mill, photo Julia Sharp.

Kersey on the left and serge on the right.

The diagonal twill on the right is formed by the weft going over two and then under two of the warp yarns. Swatches from Coldharbour Mill, photo Julia Sharp.  Racks for hanging the serge up to dry - the cloth was fixed to the rack with tenterhooks.

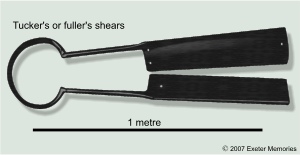

Racks for hanging the serge up to dry - the cloth was fixed to the rack with tenterhooks.  The shears were used to remove knots and the nap from the surface of the cloth. They were 4 ft long and weighed 28 lbs (12.7 kilos).

The shears were used to remove knots and the nap from the surface of the cloth. They were 4 ft long and weighed 28 lbs (12.7 kilos).

│ Top of Page │