History of the Exe Bridges

Page updated 25th February 2019

Also see Bridges of Exeter

There have been five known, permanent bridges across the Exe since the middle ages. Some historians think there may have been an earlier Roman, stone built, bridge but no archeological evidence has been found for such a structure. It is known that during the Roman and Anglo Saxon times, the river was tidal and much wider and shallower, so that animals and carts crossed via a ford at low tide. There is some evidence from written accounts for a rickety, wooden walkway for pedestrians.

There have been five known, permanent bridges across the Exe since the middle ages. Some historians think there may have been an earlier Roman, stone built, bridge but no archeological evidence has been found for such a structure. It is known that during the Roman and Anglo Saxon times, the river was tidal and much wider and shallower, so that animals and carts crossed via a ford at low tide. There is some evidence from written accounts for a rickety, wooden walkway for pedestrians.

The earliest possible record of a ferry crossing the Exe appears in the "Letters and papers of John Shillingford, Mayor of Exeter 1447-50". Shillingford petitioned funds to repair Exe Bridge.

"Where of longe tyme and wythynne tyme of mynde was another brigge no way but by right a perillous fery bote; by which tyme were yn grete perill and meny perished and lost".

It would appear that an accident had drowned many ferry passengers, which prompted Nicholas Gervaise to build the Exebridge in 1190. Drowning was probably fairly common, both from ferry and ford.

The Medieval Bridge–1236

The first stone bridge was the idea of Nicholas and his son Walter Gervaise. Nicholas toured England raising nearly £10,000 through public subscriptions to build the bridge and purchase properties whose income funded its maintenance.

The first stone bridge was the idea of Nicholas and his son Walter Gervaise. Nicholas toured England raising nearly £10,000 through public subscriptions to build the bridge and purchase properties whose income funded its maintenance.

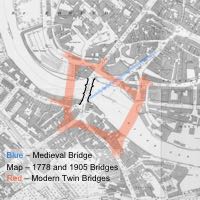

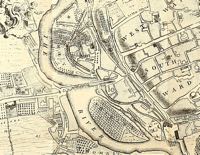

Construction commenced in 1190. The river at the chosen point was wide, subject to tides and flooding in winter–when the water was low, mud flats and shingle banks were exposed. The bridge would stretch from just below the West Gate to the banks of St Thomas, along the line of an existing weir. Built from volcanic stone quarried from Northernhay, near the castle. The piers were supported on oak piles driven into the mud. It had 17 or 18 arches (about 230 metres in total length) and three chapels, two at the West Gate end, and one at the St Thomas end. The main flow of the river was through the western arches, while the eastern half, under the West Gate appears to have been over shallow water and mud flats–easy to reclaim in the coming years. It was probably the third stone bridge to be completed in England, the first being London Bridge.

The bridge was completed by 1238. The length of time to build the bridge is reflected in the shape of the arches, with some round and some pointed, Gothic style, of which no two are alike. Maybe two generations of masons will have worked on the bridge, changing construction methods according to circumstances and available materials, accounting for the variety of shape in the arches.

Because the bridge was narrow, there were recesses over each pier for pedestrians to wait, while a cart or animals crossed. Indeed, farmers would have driven herds of cattle across the bridge to market. As was common at this time, there were houses built at each end, on the side, supported on the shingle and mud banks. St Edmund's Church was built over two of its arches at the eastern end, with a chantry chapel dedicated to St Mary on the opposite side of the roadway. A third church, St Thomas the Martyr was constructed at the western end, in the mid 13th Century, which served as the church for St Thomas, but it was swept away in a flood, a few years later. The citizens built a new St Thomas Church inland, away from flooding.

Nicholas Gervaise didn’t live to see the completion of the bridge–some histories state he was buried in St Edmund’s Church, although he was most probably buried in St Peter’s Yard.

Walter Gervaise, died in 1256–his will stated he wanted to be buried near his father in St Peter’s Yard. Some say he was buried in the Chantry Chapel of St Mary, which he and his first wife Alice had founded. (According to George Oliver, when the chantry chapel was demolished in July 1833 the workmen discovered a tall skeleton under the floor which was then re-interred on the site.) Gervaise also left two-thirds of his property to maintain a chaplain in the chapel on the bridge.

Flood damage

Jenkins chronicled some of the many floods that affected the bridge. In 1286 he wrote "the summer proved very wet; which caused great inundations; a considerable part of Exe-Bridge was carried away by the high waters". and in 1384 "A great flood happened, which carried away part of Exe Bridge, and several people were drowned."

St Thomas the Martyr Church at the western end was damaged in floods, and demolished. In a flood in 1412 the bridge was so damaged that it was estimated that £2,000 would need to be spent to repair it. In November 1539 a central arch collapsed into the Exe, requiring the aptly named Warden, Richard Bridgeman to have it repaired. Stone from the recently dissolved St Nicholas Priory was used for the repair, including the shaft of an ancient cross. Hoker wrote "... and then the prophecie was fulfilled, which was, as it was then saide, the ryver of Exe should run under St. Nicholas Church." The cross was saved in 1778 when the bridge was demolished for a new bridge, and it was moved to the corner of Gandy Street. It is now in RAMM.

Two officers, known as the Wardens of the Bridge were created to look after both Exe Bridge, and Cowley Bridge. Their responsibilities included searching the bridges and banks for defaults requiring repairs. The Head Warden was to collect rents, fees and the payments related to the bridges, pay workmen, and keep accounts. He was to ensure houses on the bridge were repaired. He was to ensure Exe Bridge was kept clean and “no Dunghills, nor Heaps of dirt, so lie upon the same.”

In 1775, tragedy took place in a public house named the Fortune of War, which was built on the bridge. A fire broke out which could not be extinguished by the local engines, even though they were close to the river. Twenty people died in the conflagration, many of whom were vagrants who lodged at a penny per night. The cause of the fire was thought to be some of the occupants melting brimstone over a fire for making matches, to sell during the day.

In the early years of the reign of George III, it was apparent that the bridge had to be replaced.

The Georgian Bridge–1778

The Exeter Turnpike Act was passed in 1769, requiring, among other projects, to build a new Exe Bridge. The plan required that the new three arch bridge be aligned with the end of Fore Street, where the derelict All Hallows on the wall was situated. The church would be demolished and a viaduct constructed to slope down and meet with the new bridge.

The Exeter Turnpike Act was passed in 1769, requiring, among other projects, to build a new Exe Bridge. The plan required that the new three arch bridge be aligned with the end of Fore Street, where the derelict All Hallows on the wall was situated. The church would be demolished and a viaduct constructed to slope down and meet with the new bridge.

The aptly named Mayor, Thomas Flood, laid the foundation stone on 4 October 1770. Not all approved of the design and at a public meeting in 1773 a resolution was passed “That the bridge was extravagant in its dimensions, of partial use, ill-chosen in site, and a Bridge that must prove a lasting subject of ridicule.” The dissenters need not have worried as storms in March 1774 and January 1775 , and the consequent flooding, swept the partly built structure away, at the St Thomas end. Bad workmanship, including inadequate foundations for the piers was blamed, and the architect was sacked.

Once the stones had been retrieved from the river, and John Goodwin appointed as architect, a new foundation stone was laid on 15th July 1776, by Chancellor Nutcombe. By 1778 the bridge was completed at a cost of £30,000.

It was opened in 1778, along with a new approach from the city, now known as New Bridge Street. In addition, Fore Street hill was lowered from St Johns Church to even out the slope. The new line and entrance to the city made a much easier route into the centre, especially for pack-animals and heavily laden carts and coaches. The first traffic across was a funeral cortège.

The extra large piers that were built, from the lessons of the destruction of the partly built bridge in 1775 proved to be an obstruction to water flow, and flooding, which was always a hazard in St Thomas increased. Over the years, the steep hump of the bridge became more troublesome, and along with the flooding problem, the City Council started to consider a replacement.

One solution to the approach to the crown of the bridge was made by Thomas Kerslake, who owned a local foundry. He suggested in 1871 to the City Council two remedies for the bridge. The first was to remove the top of the bridge down to the piers and span the gaps between the pier with iron girders, thus flattening the roadway. This was turned down as it did not fix the problem of the piers obstructing the water flow. His second proposal was to build a three span iron bridge, with iron piers, thus reducing their profile in the swirl of water. The committee who considered the proposal turned both down on the basis that a single span bridge would be preferable.

The Edwardian Bridge–1905

Despite the inadequacies of the old bridge, the City Council prevaricated over a replacement until the new century, with planning starting as early as 1899. The horse drawn tram system was proving to be unreliable and slow, but it was the development of the electric tram that gave the Council the impetus to do something about the bridge. Their solution was nothing, if not radical–they would build a new, flatter bridge suitable for electric trams, and provide the electricity generating capacity from new power station close to the canal basin. There would be the added bonus of extending the electricity system throughout the city.

Despite the inadequacies of the old bridge, the City Council prevaricated over a replacement until the new century, with planning starting as early as 1899. The horse drawn tram system was proving to be unreliable and slow, but it was the development of the electric tram that gave the Council the impetus to do something about the bridge. Their solution was nothing, if not radical–they would build a new, flatter bridge suitable for electric trams, and provide the electricity generating capacity from new power station close to the canal basin. There would be the added bonus of extending the electricity system throughout the city.

Serious plans were started in 1901, The new bridge was designed by Sir John Wolfe Barry, and Mr Cuthbert A Brereton. The design was based on what is known as the 'three hinged arch', which for the time gave the flattest bridge then in existence in the country. It weighed a total of 430 tons with a 110 ton parapet. Blackenstone Quarry near Moretonhampstead provided the the granite masonry. There were eight arch ribs, each with its own hinge in the centre and at the abutments. The roadway of the old bridge was 25 feet, while the new was 34 feet-the roadway was paved in wood blocks to reduce noise, both from horses, and iron rimmed wheels, and the pavements were of Victoria stone. Provision was made for services such as gas, water, electric, telegraph and telephones to be installed beneath the pavements.

The steel in the construction weighed 430 tons while the cast iron of the ornamental facework and parapet was 110 tons. The total cost was £25,000, which included the constructing the temporary wooden bridge, and demolition of the old bridge.

The construction was designed to withstand expansion and contraction caused by fluctuating temperature. Wolfe Barry also designed Tower Bridge, and the similarity in design, apart from the lift mechanism, is apparent.

Demolition

Work started in 1903, when a temporary wooden footbridge was constructed and the old Georgian bridge demolished to make way for Wolfe Barry’s steel and cast iron bridge. The stone parapet was sold off, to reappear outside several locals properties, including the entrance to Hamlyn House Exwick. Parts of the parapet can also be found on the left, going down New Bridge Street. Some stone from the body of the bridge was purcahsed to decorate a house of a local. Only one accident of any importance happened during the work, when a portion of one of the arches fell during the night and sank the barge beneath.

Construction of the new bridge

On 23 July 1904, the Mayor, Councillor F J Widgery laid the cornerstone, and work commenced. Coffer dams were constructed on each side of the river to allow the masonry abutments, to be constructed. The body of the bridge was pre-constructed, making the total build only eight months.

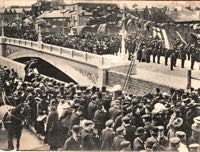

In 1905 the new, stronger and flatter bridge was completed and opened on 29th March 1905 by the Mayor, Councillor C Perry. The opening was attended by a large crowd, with some climbing onto roofs to view the ceremony. A rope was stretched across the roadway which was cut by the Mayor.

An extended tram system was opened to St Thomas, along Cowick Street, with a new line to Stone Lane along the Alphington Road, following in 1906.

This bridge lasted for some 70 years, when, after the floods of 1960 twice covered St Thomas on the west bank, it was decided to replace it as the structure tended to hold high water back and increase the chance of flooding, and traffic volume was increasing to a point the the bridge was now a bottleneck. When the bridge was demolished, three lamps were moved to the quay and two now mark the opposite sides of the river, where Butt's Ferry operates. The body of the bridge, made from iron was taken away, on flat trailers, in sections to a scrap yard in Newport, Wales.

Thomas Sharp in his book, the Exeter Phoenix, he proposed a northern by-pass to meet up with the Exe Bridge at a cloverleaf junction. He had no proposal for replacing the bridge, and it was not until the floods in 1960, that the inadequacy of the bridge became obvious.

The twin bridges–1972

The double flood of 1960 exposed the 1905 bridge to the ravages of deep and wild water–as the water rose, the shallow arch was immersed putting a high pressure against the structure. In addition, the enormous growth in traffic since 1905, when the largest vehicle to cross the bridge was the eight ton tram, sheep and cattle where no longer driven over the bridge to market, as it had moved out to Marsh Barton.

Plans were drawn up and work started in 1967 to build two bridges, one on each side of the old 1905 structure. The work would also involve turning the river into a virtual canal, with a wide path just above water on each side, and a concrete bank above. Keir were the contractors, and soon they were scraping back, and consolidating the river bank along Bonhay Road. The two slim piers were constructed on concrete, after a coffer dam had been constructed to allow foundations to be sunk into the river bed.

By 1969 the north crossing was complete and opened by Mayor Bill Hallett on a sunny day in July, who then rode across in the Mayors car. The crossing, along with the old bridge became a roundabout, until the southern crossing was finished. The south bridge was opened in 1972, allowing the 1905 bridge was taken apart, with the iron parts going for scrap.

The twin bridges are strictly functional, built out of concrete and forming, between them, a large roundabout system, that at times, seems to be permanently jammed. The piers have been designed to aid the flow of water during flood and the banks of the Exe have been concreted, also to aid water flow. There is no trace of the Georgian or 1905 bridge left.

The road system to feed the twin crossings were also extensively re-worked–Edmund Street, once a major route through the city, in the 1950s. was no longer needed, so demolition commenced. After the houses on each side were removed, and the road surface stripped off, far more of the original medieval bridge was uncovered, than expected. Work was halted when St Edmund's was partly demolished and the archeologists were called. It was soon decided the as much of the structure should be retained. The old bridge was in the centre of a large gyratory traffic system. The City Council decided to landscape the site, and the exposed seven arches, the tower of St Edmund's stabilised. Although a traffic island is not an ideal environment for such an important architectural site, this important historical feature is preserved for posterity.

Sources: History of Exeter by Rev., Oliver, Exeter Cathedral Library and Archive. British Newspaper Archive. Official Programme for the opening of the 1905 Exe Bridge.

│ Top of Page │