Exwick's 'Woollen Mill and Factory'

Page updated 16th July 2010

Exwick's largest and most extensive mill, was not built until 1786, after a young Antony Gibbs, a budding woollen merchant and son of George Abraham Gibbs, of Clyst St George had gone into partnership with the Exeter merchant Edmund Granger. Granger produced £10,000 for the new business, while George Abraham Gibbs pledged £5,000. Producing woollen serge had made Exeter a prosperous city during the late 17th and for most of the 18th Centuries, and Antony Gibbs wanted to emulate the successful Baring, Kennaway and Duntz merchant dynasties, who had become rich from wool.

Gibbs, with his brother Abraham, had been running a serge exporting business to Spain from 1778, and had spent time in the country, becoming fluent in the language. His brother had died in 1782 leaving him to run, with some concern from his father, the business alone. His friend, Samuel Banfill had spent a year in Spain drumming up business for him during 1783/4. Banfill would become the third partner in the new mill in 1787 and he became family when he married Anne Gibbs, Antony's sister. With Granger acting as the accountant, and Banfill as the manager, Gibbs purchased in 1785 the remaining 60 year lease on the Higher Fulling Mill, one of three wheels at Exwick Corn Mill, further up the leat, to full his cloth. It is not clear how long this mill remained fulling for the company, but by 1815, the wheel had reverted to driving stones to mill corn.

A New Mill in the Village

The estate of Exwick Barton came up for sale – the estate included Exwick Manor House of which the corner site of the Village Inn was part, various cottages and other buildings including the Hermitage on Exwick Hill, and some land straddling the leat below a fulling mill that was already working for John and Charles Baring; this mill is remembered by many as the old County Steam Laundry. The Barings ran their business from Larkbeare House in Holloway Street, where the workshops and warehouses devoted to dying and pressing of the fulled serge were located.

Gibbs purchased the house, land by the leat and other property in the village and built a new mill opposite the present site of the Village Inn. He had 31 elm trees cut down, several loads of stone and 3450 bricks delivered in 1786 for the new complex. The new mill drove spinning machines and other equipment to finish the cloth. Dye and washing houses were built next to the leat, on the site of the present Exe View Cottages. Counting houses, warehouses and weaving shops were constructed in the Square, Exwick Hill and on the site of Rackfield Cottages. Housing for the factory workers were also constructed on Exwick Hill.

By 1789, it was obvious that Antony Gibbs had over extended himself, borrowing from Granger, Banfill, his father, and others, and failing to pay many outstanding bills. His position was dire, and a letter in the Flying Post summed up his standing with one disgruntled, if poorly educated member of the local community:

"Jan. 12, 1787

Mr. Antony Gibbs i have took this

opportunity in sending thes few lines as a frindly Caution Concerning

many Destervence that have hapned Times past you Damnation Black

Skandlous Dog now to be very Pecuhlor i Cant stop about it to your very

Great Surprise you shall find your litle Pile of Buldings one Morning

all in flams and not only your Buldings but you will find the Racks cut

from end to end you Damnation Black Dog.

Excuse the writing.

To

Mr. Antony Gibbs and Co. Merchants

Exweek Devon"

Gibbs, Granger and Banfill offered a reward of a £100 for the conviction of the offender responsible for the threat.

Trade for other Exeter merchants during the late 1780s was not good either, and there had been some failures of merchants in the city, as the French Revolution caused turmoil across the European markets. Things went from bad to worse when the banks refused Gibbs credit and he was declared bankrupt, owing £18,000, forcing him to leave the partnership. The true value of Gibbs' debt at today's value, measured against average earnings, is £20,800,000 – even when measured against the retail price index the loss was more than £1.7 million. His father, as a major investor, was also liable and in 1789, he was also bankrupted, for the even larger sum of £22,000.

It was decided that Gibbs would return to Madrid and act as the Banfill and Granger agent, with any earned commission going towards paying off his debts. Gibbs' reckless business acumen and habit of extending easy credit to his customers saw little of his debt repaid.

By 1807, Antony Gibbs had returned to London with his family, still heavily indebted to his former partners. He founded the House of Gibbs, and died in 1815, aged 59. His son, William Gibbs would in the 1850s, make a success of the business with the importation of guano for use as a fertiliser, and it was through bird droppings that William Gibbs, a conscientious and pious individual, eventually paid off his father's debts. He became the wealthiest businessman in England, and purchased Tyntesfield, near Bristol, now a National Trust property. He would also use some of his wealth building St Michael's Church, Mount Dinham and extending Exwick Church.

Antony Gibbs' brother Vicary was a successful lawyer who would become Attorney General between 1807 and 1812. He purchased the estate from the company and leased the woollen mill back to Banfill and Granger, while at the same time, selling Exwick Barton to the Rev., Duke Yonge of Pulsnich. Samuel Banfill moved into Exwick Manor House to run the mill free of Antony Gibbs, and the business survived through difficult times, as the French market was lost.

From about 1790 an important output was long ells for the East India Company who exported to China in exchange for tea. Russell's Wagons were used to transport the cloth to London to be loaded onto the Company's ships lying in the East End docks. Long ells were also exported to China illegally, bypassing the East India Company, but it is impossible to know if any of Exwick's output was traded through these channels.

Alexander Jenkins, in his book, The History of Exeter, published in 1805, described the woollen factory thus:

"In this hamlet Edmund Granger and Samuel Banfill, Esqrs. have established a large woollen manufactory, and erected spinning machines, workshops, dye-houses, tenter grounds, &c.; also dwelling-houses for the manufacturers, an establishment which has greatly increased the number of inhabitants; here is Exwick House, once the residence of the family of Oliver, from whom it came by marriage to William Williams, M. D. of Exeter; it was the residence of his widow for many years, whose heirs sold it, with the Barton, to the present proprietors of the manufactory. It is now the residence of Samuel Banfill, Esq. the directing partner of that extensive concern."

Edmund Granger retired in 1813, and a new partnership of Banfill and Shute was formed. The factory during this time was producing woollen shawls and cashmere. By 1819, the partnership was declared bankrupt.

On 20th March 1820, a sale notice for the factory and mill appeared in the Sherborne Mercury. It is worth listing the details of the sale as it indicates how extensive the woollen factory in Exwick was. There were 6 acres of land, and a 3 storey mill - the ground floor had gear work from the water wheels running four shearing frames, each working 4 pairs of shears, a brushing and napping machine, a calendar and cylinder and two breakers. The second and third floor had thirteen scribbling and carding machines, five billies, eight jennies and one breaker. There were also 20 jennies working in other buildings, a dye-house, a building containing two blue vats heated by five flues, two large copper furnaces heated by steam, two wool vats and a drying loft.

Samuel Banfill seems to have had no further involvement with the mill after 1820 and in 1830, he moved out of Exwick Manor House, into the Hermitage which was up Exwick Hill. He died in 1843 at the age of 78. The old house seemed to have deteriorated over the ensuing years and surviving deeds for the buildings now on the site suggest it was demolished around about 1860.

George Shute took on the factory in his own right, and Penny & Rawlinson, lace manufacturers leased part of the complex. However, Shute's involvement with the mill ended with his death in 1822.

By 1824 the factory was for sale again, described as the property of George Shute, deceased, and occupied by Penny & Rawlinson, and George Shute & Sons. It would appear the factory was not sold as a going concern and the machinery for Shute's Mill was put up for sale by auction in Trewman's Exeter Flying Post of 25th May 1826. There was no success, for on 20th March 1827, the concern was again for sale, along with the lace factory which was still leased by Penny and Rawlinson. Their lease was to expire in December 1829. This sale included 20 cottages for the workers.

Hitchcock, Maunder & Hitchcock

Robert Maunder, who was born in 1801 in Morchard Bishop, had become a woollen manufacturer, with mills in towns across Devon. He purchased Exwick mill from the estate of Vicary Gibbs in 1831. Included in the sale were the counting houses, weaving shops and workers cottages, all of which sold for £1,100.

The mill continued production through several combinations of partner, and by 1844 it was Hitchcock, Maunder and Hitchcock, who also ran mills in South and North Molton. The 1851 census indicates there were about one hundred and twenty workers from Exwick at the mill, most of whom were born in Devon – the breakdown of the area of birth of the majority were – St Thomas 15, Crediton 13, Morchard Bishop 10, Buckfastleigh 10, South Molton 9, Cullompton 6, North Tawton 5, Tiverton 4 and Newton Poppleford 3. The census gives a rough breakdown of the work available at the mill – weavers 32, spinners 26, woolcombers 23, wool sorters 11, burlers 7, wool carders 2, and fullers 4. Slaters directory for 1852 states that Hitchcock, Maunder and Hitchcock were serge and blanket manufacturers. See 1851 workers list.

However, even though the employment figures appear to be healthy, Exeter's woollen industry barely had the strength to draw breath, and chasing ever more diverse and specialised markets was no longer productive; this was not an industry on its last legs, it was an industry with no legs at all.

The Flax Mill

In early 1859, Maunder leased the mill to Thomas Carter and John Richard Treble, who traded under the name of Thomas Carter and Co. as flax dressers and manufacturers of woollen goods. The manager was 27 year old Joseph Corr, a Northern Irishman, who was married with a small child and baby. A series of six adverts were placed in the Flying Post addressed to farmers, to purchase their fields of flax. It seemed like the new wonder crop, but a court case, in 1860, over the ownership of a field of flax destined for the mill must have caused problems and soon after, on the 10th August, Carter and Treble dissolved their partnership, with John Richard Treble continuing alone in the business.

A marked change was evident in the workers at the mill in the 1861 census, when compared with ten years before. The number of workers had dropped from one hundred and twenty in 1851 to forty-one workers including the manager. The introduction of flax production required new skills and eleven flax workers were imported from Ireland. There were only eleven weavers working the machines, three woolcombers and four spinners; for the first time for many years there were no fullers working the stocks. A few of the workers from 1851 still worked for Treble in 1861. See 1861 workers list.

On the 2nd October 1861, the Flying Post contained a report on a disastrous fire at Messrs Treble & Company's Mill the previous day.

"About four o'clock yesterday (Tuesday) morning a destructive fire occurred at the serge and flax mills situated at Exwick, the property of Mr Maunder, in the occupation of Messrs. Treble and Co. The brigades belonging to the fire engines in the city were soon in readiness with the engines but some delay occurred in getting the horses, and the engines were consequently not so quickly on the spot as they otherwise might have been. The West of England brigade was followed by those of the Sun and Norwich Union Offices; water was abundant, and by their united exertions the flames were confined to the mill, which is entirely destroyed. Two ricks of flax, valued at £150, and adjoining the scene of conflagration, were thus prevented from igniting; as also some house property belonging to Mr. Moore, builder, and others. The fire originated in the boiler or "skimps' room. A large quantity of machinery, to the value of from £2,000 to £8,000, was destroyed. Mr. Maunder is partially insured in the West of England Fire Office, and Mr. Treble in that of the State Office. In consequence of this disastrous fire, nearly two hundred hands are thrown out of employment." The newspaper computed that two hundred lost their jobs, but as already mentioned, the census puts the figure at a much lower number.

In September 1862 a notice to let appeared in the Flying Post "Exwick Mills, Exeter... extensive range of mill property... for many years occupied by Messrs Maunder as a woollen factory and Messrs Harris as paper mills, and are now to be let in consequence of the recent destruction of the former by fire..." The advert went on "The late woollen mills are situate about fifty yards lower down the same stream, and command the same volume of water as the paper mill."

James Wentworth Buller purchased the site of the former woollen mill along with the paper mill in 1862. The ruins of the mill also included an intact brickbuilt warehouse of three stories, one hundred and thirty feet long by twenty feet wide, which was later used as a store for Mr Kempe and others.

The second fire

The mill was never rebuilt, but Mr Kempe's warehouse of the 'Old Flax Mill' also fell victim to the errant spark, when it was destroyed by a huge blaze on Saturday 17th April 1869.

"The old Flax Mill at Exwick, near Exeter, was destroyed by fire on Saturday night. The premises stood apart from any other building; and as the wind was blowing from Exwick village to the St David's Railway Station there was no apprehension that the fire would do any other damage than to the premises wherein it was raging. No very great efforts were, therefore, made to extinguish the flames; and the fire was allowed to "burn itself out." Nothing now remains save the outer walls and a chimney or two. The premises belonged to Mr. J. H. Buller, of Downes, and it is believed they were insured. The fire is attributed to an incendiary." Flying Post

The fire continued to burn until six or seven in the morning, leaving the remaining walls of the building in a dangerous state. This was the last act in a story that commenced in 1786 with a dream of Antony Gibbs for a woollen mill and factory to rival those that were flourishing in the north.

By 1878, a map drawn up to show some new fencing for the Buller estate shows a small bridge straddling the leat where the mill had been positioned; the leat has since been filled, but where the narrow road turns sharp left before Exe View Cottages, is the site of the mill. Exe View Cottages are marked on the map on the site of the warehouse that burnt down in 1869, dating their construction to between 1869 and 1878.

Nothing now remains of a mill complex that some compared with the large industrial mill towns of Lancashire.

Sources: Flying Post,Times, Western Times, Sherbourne Mercury, records from the Buller estate in the Devon Record Office, Fragile Fortune by Liz Neill, Road Transport Before the Railways by Dorian Gerhold and various trade directories.

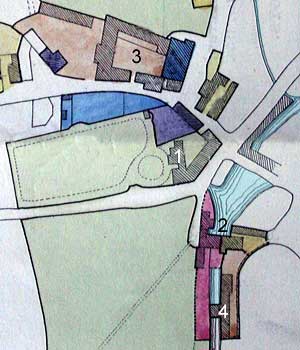

1 Exwick Manor House, 2

Gibbs' woollen mill, 3 The Square, 4 Exe View Cottages.

1 Exwick Manor House, 2

Gibbs' woollen mill, 3 The Square, 4 Exe View Cottages.

Exwick Manor House from the only known

painting, probably mid 18th Century. Notice the tall trees to the right

– these were probably the elms that Antony Gibbs' had cut down

for his mill.

Exwick Manor House from the only known

painting, probably mid 18th Century. Notice the tall trees to the right

– these were probably the elms that Antony Gibbs' had cut down

for his mill.

This photograph, taken from

the top of the old Exwick post office shows Exe View Cottages during

one of the frequent floods. The area in front of the cottages, to the

left of the shed is where Antony Gibbs built his mill. The thatched

cottages have since been demolished.

This photograph, taken from

the top of the old Exwick post office shows Exe View Cottages during

one of the frequent floods. The area in front of the cottages, to the

left of the shed is where Antony Gibbs built his mill. The thatched

cottages have since been demolished.

Wool

Processing Machinery Terms

Billie - definition not known

Breaker - breaking up the

fleece and grading it. Carding - combing the cloth to align the fibres.

Jenny - a machine for spinning

yarn.

Scribbling - adding olive oil

to the cloth to make it easier to work. The oil known as Gallipoli oil

was imported through Bristol.

Shears - mechanical shears that

removed the nap from the cloth.

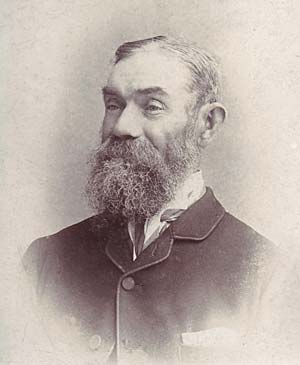

Joseph

Corr, was manager of the flax mill from 1859 until its destruction in

1861 – photo taken when he was in his fifties. Courtesy of Richard Corr.

Joseph

Corr, was manager of the flax mill from 1859 until its destruction in

1861 – photo taken when he was in his fifties. Courtesy of Richard Corr.

│ Top of Page │