- Home

- Memories

- Scrapbook ▽

- Topics ▽

- People ▽

- Events

- Photos

- Site Map

- Timeline

Page updated 25th January 2011

The ancient Manor of Exwick is distinguished more by how little has happened, rather than what has happened, through the ages. No grand visits by monarchs, little mention in the chronicles of the Civil War; just a small hamlet living in the shadow of the city across the Exe, with two mills to provide local employment. It takes a bit of digging, but Exwick does have a past that, although at times ordinary, is still interesting, and reflects what is going on in Exeter and across the country.

Exwick is first mentioned in Domesday, along with many other English manors. "Baldwin himself holds Exwick. Everwacer held it Tre, and it paid geld for 1 hide. There is land for 8 ploughs. In demesne (land belonging to a Manor House) is 1 plough, and 5 slaves; and 9 villans (peasant) with 6 ploughs. There is a mill rendering 10s. , and 3 acres of meadow, and 50 acres of pasture and 3 acres of scrubland. Formerly 20s. now it is worth 30s."

William I handed all of this, along with 158 other manors in Devon to his nephew, Baldwin de Brionne, which was a bit of a liberty because Exwick had formerly belonged to the Saxon, Eureuuacus.

Now Baldwin's son inherited Cowick and Exwick from his father, and being a pious lad he generously gave the two manors to the Abbey of Bec, which was close to the families ancestral home in Normandy. The Abbey set up a daughter priory at Cowick Barton, which in turn, set up outposts at Exwick.

There is evidence of milling in Exwick from Saxon times, and Domesday mentioned a mill in the manor. In 1189, the monks of Cowick Barton purchased 2 acres of meadow at Duryard to build a weir across the river to feed their mill of St Andrews with water. It is probable that parts of the leat was a natural channel, running parallel to the main river, which was cleared and deepened to drain the surrounding land. There was certainly a flour mill established on the Exwick Mill site by the monks of St Andrew's by 1345.

By the time that the small hamlet was known as Exewyke, in the mid 13th Century, the mill and hamlet were occupied by the Monks of Cowick Priory. Cowick and Exwick were more or less run by the Cowick Prioryor the Abbots of Tavistock until its dissolution in 1535.

Exwick Manor House had belonged to the monks of St Andrews before being passed on to the Earl of Bedford, Lord John Russell in 1539. Exactly one hundred years later and William Gould of Hayes purchased St Thomas, Oldridge and Exwick.

Exwick was on the periphery of events during the Civil War sieges of Exeter, first by the Royalists and then by Parliament, under General Fairfax. In the final siege, in late January 1646, Exwick Mill, along with Barley House, Bowhill House and Marsh House, were fortified, and Parliamentary troops were billeted in Exwick Manor House.

By the 1660s, Exwick Manor was leased to Benjamin Oliver. Benjamin Oliver was knighted by Charles II in 1671, when the King travelled through Exeter on his way to London from Dartmouth. Sir Benjamin Oliver lived in a house on Fore Street Hill and maintained a country house in Exwick. He was buried in a family vault in St Thomas Church. The last of the Olivers was Mrs Elizabeth Williams who died in 1776.

The first signs of industrialisation in Exeter appeared when there was an attempt in 1754 to mine coal at Exwick Hill, on the Cleave estate. The attempt was not popular with some locals, and came to an ignoble end, when a protester threw a sledgehammer down the bore hole, breaking the drill bit. It was not to be coal, but water power that would create a woollen factory on an industrial scale, in the village.

Soon after the death of Mrs Elizabeth Williams, the old Exwick Manor House and a large area of farm land was sold to Antony Gibbs, an Exeter woollen merchant, who had gone into partnership with Edmund Granger and Samuel Banfill, to run Gibbs, Granger and Banfill, a wool factory in 1785. Gibbs initially leased a fulling mill, but in 1786 he had a new mill constructed about a 100 metres below the existing Lower Mill in the village. Antony was not a good businessman and was very soon in debt for £18,000; his father, George Abraham Gibbs from Clyst St George mortgaged his own house to help his son out, but it was not enough and they were both bankrupted. Antony's brother, Sir Vicary Gibbs had purchased the manor house for his brother to lease back, but it was eventually made over to the Banfill and Granger mill to offset his brother's debts.

The woollen factory survived, run by Granger and Banfill, and Antony Gibbs moved to Spain and later, Portugal as a merchant, where he tried to find outlets for the mills cloth, and pay off his debts. He later returned to England and founded the House of Antony Gibbs and Son in London in 1808. Samuel Banfill lived in Exwick Manor House during this time, and in 1795 married Antony Gibb's sister, remaining in the house until 1830.

Jenkins wrote early in the 19th Century of the factory:

"In this hamlet Edmund Granger and Samuel Banfill, Esqrs. have established a large woollen manufactory, and erected spinning machines, workshops, dye-houses, tenter grounds, &c.; also dwelling-houses for the manufacturers, an establishment which has greatly increased the number of inhabitants;"

The business became extensive, developing into a large woollen factory, complete with dye and washing houses, spreading from the leat up Exwick Hill. The Lower Mill was the key to the complex, providing power for finishing the cloth; it was an industrial style building, built over the leat, 50 metres or so below the paper mill in the centre of the village. The heyday of the factory came to an end when Mr Banfill retired in 1828, and moved to a cottage known as the Hermitage in 1830. Five attempts were made to sell Exwick Manor House up until 1832, when it was described in the sale particulars as:

"The Mansion House

Is a very substantial Building, most pleasantly situate, commanding

extensive views of the rich surrounding scenery, and is well adapted

for the Residence of a Family of the First Respectability."

It was eventually demolished, leaving just the present Village Inn as the only building remaining from the house and described in the sale as: "Another Out-House for Coach-House or Stabling, 18 feet by 18 feet, Beer Cellars, &c."

Banfill and Granger's mill was taken over by Robert Maunder, who ran it as a woollen mill until 1859, and by Treble and Son as Exwick's Woollen and flax mill until 1861, when it was destroyed for a second and final time by fire, and the loss of 40 or so jobs.

Exwick Lower Mill, a few yards upstream from the woollen factory, had its origins in the 17th Century as a fulling mill built on Benjamin Oliver's land. In 1805 it was converted into a paper mill; perhaps some of Exwick's more colourful stories of fraud, prison and early industrial action happened at the paper mill. In 1869 it had new wheels and machinery installed, and was converted to milling flour between 1872 and circa 1890. It become the County Steam Laundry with Frederick Edgar as manager in 1893. The house now known as Exwick House was built sometime after 1830 as the mill house for the paper mill.

The parish, although small by modern standards, was now considered to be large enough to need a church of its own. The Exwick Chapel of Ease was planned by the Rev John Medley who appointed as architect, the young John Hayward, who went on to design the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and St Lukes College. James Buller, father of the General, donated the land and £100 towards the cost, and local man John Moore was contracted to build it. See St Andrew's Church for a full history.

The Victorians became increasingly interested in creating public amenities, which, in Exwick, resulted in the cemetery at Landhayes opening on 30 March 1877, in a ceremony officiated by Bishop Temple, who later became Bishop of London and then Archbishop of Canterbury, and whose son, also William Temple, was also Archbishop of Canterbury. The first burial was that of Elizabeth Curry who died at the age of 29, and, as the first, was given a free tombstone. Sadly, the next year, her small son was buried next to her and two years later, her husband. Proceedings concluded with Miss Champion playing the harmonium. The cemetery also contains the grave of the Victoria Cross holder, George Hollis, who died in 1879. He was awarded the honour during the Indian Mutiny in 1858.

James Wentworth Buller, father of the venerable General Redvers Buller, still owned much of the land and property in Exwick in the middle of the century. He donated the land for the school opposite the church which opened in 1861. The toll house was built to serve the turnpike between Exwick and the Seven Stars Hotel in St Thomas in 1853.

As chairman of the Great Western Railway, Buller was able to insist that traffic could cross the railway line, opposite the Red Cow Inn, and consequently, in 1851, he raised funds by subscription from locals to pay for two wooden bridges across the leat, and the river. A private road from St Andrew's Road to the bridges, across his land was cut, and from 1855 tolls were collected at the toll house; Buller allowed the 'labouring classes' to pass along it for free and a board at the toll house stated "Private Road - No passing without payment of toll, excepting for foot passengers."

After 70 year old Mr Palmer was killed attempting to cross the thirteen lines, while pushing a wheel barrow, in 1860, the GWR wanted to close the crossing, but were overruled. A year later, the bridge over the leat was replaced with a more substantial structure using iron-girders and masonry at a cost of £270. In 1866, the wooden bridge over the river was badly damaged by floods and by 1870, it was in poor condition; it was rebuilt in 1871 at a cost of £1,200 in cast iron and stone. Station Road as it is now known was adopted by the City Council in 1901, and the collection of tolls was stopped. See Station Road for a longer history.

In 1872, the guano king, William Gibbs of Tyntesfield, the son of Antony Gibbs who had been involved in the woollen factory back in the 1780's, built St Michael's Church, at Mount Dinham, and bought the living of Exwick from General Sir Redvers Buller, to make it independent of St Thomas. He also had Exwick Church enlarged by lengthening the chancel and adding extra width. Antony Gibbs, William's son, paid for the building of the post office and store, with its mock Tudor style turret, designed by Walter Cave, and built in 1893. Lead rainwater heads with the initials AG, and the date 1893, were installed. Cave was a young, respected architect, who had already worked for Gibbs, designing the Orangery at Tyntesfield. He was influenced by the arts and crafts movement, as well as Jacobean, Queen Anne and Neo-Georgian styles, and it shows in the eclectic style of the post office building; his practice closed in 1935.

The Exeter Flying Post is an invaluable resource for local history, and taking 1877 as an example, chronicled some typical events during the year. Several meetings of the school board took place and it was noted that there were 124 children on the register, after a new schoolroom had recently been added. In May, a 15lb salmon was caught from the marshes just above the village, despite the pollution that Exeter poured into the Exe.

A young woman, named Fanny Smith, was fined 40s and costs, or two months in prison when she was found with two rabbits and a net, probably trying to supplement the family diet. The Exeter Working Men's Conservative Union held their annual fête in the grounds of Cleve House in the July. During the August the Exwick and St David's Second Eleven scored an impressive nine wicket victory over the Exe Valley CC; highest score was made by J Wreford with 19 not out, and R H Rowe with 14, giving a total for the innings of 64. And in October a tender was accepted from Mr Isaac Heard for lighting the street lamps of Exwick at a cost of £3 5s per lamp, or £19 10s for all of them; this was no simple task as the lamps were fuelled by Alexandra Oil, and would have required lighting at night, and snuffing in the morning, as well as filling the tanks and attending the wicks. In the November, the Board reported that the lighting of the lamps had been satisfactory - committee work never changes.

The Rev W C Gibbs was refused permission to use a room in the school for his Sunday School pupils. The reason given was that there were now a great number of Dissenters in the parish who were barred from using the school, and it was not thought right that it be available to the Churchmen and not them. On 9 December, Ellen, eldest daughter of Mr John Webber married Mr Bell of Bristol at Exwick Church.

Exwick was a very different village at the turn of the twentieth century, in comparison with just thirty years earlier, as the needs of industry and commerce evolved in Exeter. The population of Exwick parish at the 1901 census was 527, consisting of 251 men and 276 women. Adding those living in St Thomas, but part of the Exwick electoral area, including Redhills and Barley the population was 780.

Malletts Mill was now a large and efficient operation, employing twelve including William Richard Mallett and his wife. There were now two full time waggoners to bring the corn to the mill, and distribute the sacks of flour to local bakers and beyond. The railways also employed a large number of mostly manual labour from engine drivers to signalmen and track layers. The census show 28 blue collar workers for the two railway companies, and four white collar workers, three of whom were clerks and one a foreman. The other large employer was the County Steam Laundry that had opened in 1893 in the old paper mill premises; they employed sixteen workers directly while another fourteen are listed as laundry workers at home, many probably contracted as outworkers to clean more delicate items. Even before the laundry opened, the 1891 census indicates a significant number of households existing on the taking in of laundry from the burgeoning middle classes in the city, and the needs of the local hotels and a growing tourist industry.

Exwick, along with many other small communities marched to war with a belief that it would be all over by Christmas. Reservists Tom Greenslade and Charles T Hutchings were the first to leave for France when telegrams arrived, calling them up. Seventy young men joined up in the first initial surge of enthusiasm, and over the four years of war, a total of 123 were drafted into the army and navy.

The women of the village formed a Working Party to make socks, shirts, pyjamas, Balaclava helmets, scarves and sandbags for the men at the front. In 1915, a Miniature Rifle Club was formed and 30 local men joined, to improve their shooting skills.

There were food shortages in 1917, when the German submarine blockaid reduced the importation of food to a trickle. Locals were encouraged to grow food, and 14 boys from Exwick School grew a large quantity of potatoes, in their gardening class. In October 1917 rationing was introduced, and street lighting reduced to save on coal.

Exwick Mills, with a reduced work force, milled flour around the clock to keep up full production. When the end of the war was announced on Armistice Day the school bell was rung to proclaim the news. See Exwick Roll of Honour 1914-1919.

In 1919, the sum of £107 10s was raised by the village for a war memorial. The final design was a 10ft granite cross, designed by Mr T Easton at a cost of £65, with a further £10 spent on the inscription. It was dedicated on the 26th June 1920. The Parish Hall was opened in 1921, in memory of the 1914-18 war. The land had been donated by General Buller in the previous century, and a £1 public subscription and loans raised the £700 cost. It was in 1933 that the last of the loans was paid off.

New development started to accelerate in the 1930s and in August 1934, Lord Mildmay of Flete, a director of the Great Western Railway formally opened the Mildmay Close estate. Built by the Exeter Workmans' Dwellings Co., the GWR provided 90% of the funding at 4% interest and the rest by the builder. The housing company also built the houses on the east side of Exwick Road flanking each side of Mildmay Close.

During the 1930's, there were plans to create a relief road to by-pass the corner by the toll house at the junction of St Andrew's Road and Station Road and round the back of Exwick Villas. A start was made when Valley Road was built, but was abandoned at the outbreak of the war in 1939, and the short stump of Valley Road became the entrance to Delaney Galley Ltd, a munitions factory that made equipment for cooling aircraft engines, built behind Exwick Villas. Delaney Galley manufactured car heaters before the war, and their expertise in fabricating metal containers was also utilised in manufacturing wing tanks for Spitfires, Barracuda bombers and other aircraft types.

Exwick's proximity to Exeter meant that the inhabitants of the village were only too aware of the war. They could clearly see the glow of the fires, and hear the bombs exploding, during the raids of April and May 1942; some who left the city to escape the raids ended up sheltering in the lanes and woods above Exwick. There was one report of Exwick Mills suffering shrapnel damage from a bomb that dropped close to St David's Station killing several men, while some remember the parachute mine that drifted down to explode in Landhayes Cemetery, blowing trees, bits of memorials, and some said, coffins and bodies across the road. The huge influx of US troops into the city saw a large contingent of black GI's camped at the County Ground. I have read at least one account of a grandchild searching for her grandfather, a GI who had a liaison with a girl who was a resident at Cleave House.

The top floor of the County Steam Laundry was destroyed by a fire on 2nd December 1941, when thousands of officers uniforms, workers overalls and other clothing were destroyed. As a result, Exwick House was used for repairing and tailoring and the press and ironing department utilised a vacant building behind the old mill building. The drycleaning and other equipment were saved and remained in the laundry.

There are four names on the war memorial from the Second World War:

R Fulford

T Greenslade

S Hucker

H Tucker

The Exe Valley has long had a problem with flooding and Exwick had suffered many inundations through the centuries. In the 15th Century St Andrew's was damaged by flooding, and in 1786 "...at Exweek it made great devastation". Cowley Bridge was carried away in 1809 and so on. It was the two floods of 1960 that would be remembered by many, as the catalyst for a huge civil engineering project that would change the village for ever.

The 26th October was referred to as Black Thursday. It had rained for weeks and the river had risen to overflow its banks. Station Road was a barrier to the water, with mud and silt swept through the village to a depth of 2 metres. A raging torrent flowed across the Exwick playing fields and into St Thomas, leaving washing, hanging out to dry, marooned in the back gardens of many houses. A second flood in December was equally devastating and soon plans were drawn up for a new flood channel and flood gates at Exwick, and further engineering work in St Thomas and Cowley.

Work started on the scheme in 1965, which was not completed until 1977. The new flood channel saw the ancient leat that flowed through the village filled in, and soon after, the mill building that was the County Steam Laundry demolished. In September 1974, another torrent swept down the Exe and carried away the old bridge across the river, which had been installed by the Bullers more than a century before, for access to St David's. The next day, the coastguard was called to fire a rocket, with a line attached, across the river so Post Office Engineers could reconnect 600 telephones in Exwick to the grid. A temporary pedestrian bridge was installed, before a new bridge was opened in 1976. See Station Road Bridge for more on the bridge.

After the war, in 1947, half the camouflaged munitions factory was used by the Bristol Aeroplane Company for a year and the rest converted into a bakery by Hill Palmer and Edwards, and by 1950 the production of Mother's Pride was in full swing. The company was eventually taken over by the Rank Hovis McDougall group. Bread production ceased and the site used as a distribution depot before it closed in March 1993. Very quickly the vandals moved in and every window facing the flood channel was smashed. In 1997, Westbury Builders demolished the bakery and built Old Bakery Close. Through the 1970's, Exwick was the fastest growing suburb of Exeter and new estates between Foxhayes and Cleave House spread up the hill - in 1980, the Guinness Trust expanded the village to the north along Farm Hill and Kinnerton Way.

Half a mile to the south of the village can be found Foxhayes. It was formerly a tiny hamlet of Foxhays farm, now the Thatched House Inn dating from the 1600s, and on the opposite side of Exwick Road, a post office, doctors, formerly a bakery, and garage on what was once a gipsy site. The road in front of the farmhouse was the main road; an end gable on the farmhouse was demolished to allow the road to be straightened for modern traffic and the dog leg bend removed.

And last, the defences for flooding in Exwick are never finished; the Environment Agency constructed 100 metres of flood bank on each side of Station Road in 2008 and walls were built for a mobile barrier, which fits into slots on each side of Station Road when it is thought flooding is imminent.

Sources: I must thank Alan Mazonowicz for the use of his extensive notes on the history of Exwick. Other sources include the Environment Agency website, West of the River by Hazel Harvey, Census records, Parliamentary papers of Great Britain - House of Commons, Exeter Remembers the War by Todd Gray, Express & Echo, Devon Records Office, and thanks to Liz Neill for prompting my research into the Gibbs family, plus other articles on this website.

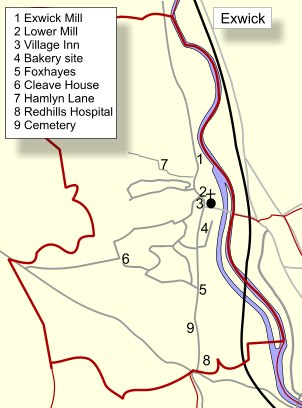

Map showing some interesting places

Map showing some interesting places

Some

Exwick Trivia

• The

population in 1891 was 566.

• The population in 1914 was 400.

• The population in 1960 was 500.

• The population in 1982 was 6,000

• In 1872, Exwick became a parish separate from St Thomas.

• Gas first reached Exwick in November 1902.

• The Station Road and bridge toll charges were removed in September

1901.

• New Valley Road was built in 1981 and was intended to continue as a

link road to Station Road.

• Exwick Recreation ground was once known as Path Meadow.

• Station Road was raised by building a viaduct in 1953 to reduce

flooding.

• There is a 1861 advert for Exwick's Turkish Baths, five minutes

from St David's Station. A newspaper reports the partial destruction by

fire, of the baths in 1863. Nothing more is known about the facility.

• Exwick Villas were built in 1935, at a cost of £500 each.

• The Exwick flood channel cost £4 million.

• The Toll house was the last Exwick property owned by the Buller's

to be sold out of the family, in 1988.

• Weircliffe Park is the base for Weircliffe International Ltd,

manufacturers of degaussing equipment (magnetic tape erasers).

They

started in Wiercliffe House as Amos International in the 1960's.

• Exwick Health Centre, at the end of New Valley Road was built in

1985.

Part

of a photo taken from Station Road showing the centre of the village.

Left is the Village Hall, right is Exe View Terrace and centre the

County Steam Laundry. The leat runs right to left across the centre of

the photo. Photo courtesy of Dennis Hammond.

Part

of a photo taken from Station Road showing the centre of the village.

Left is the Village Hall, right is Exe View Terrace and centre the

County Steam Laundry. The leat runs right to left across the centre of

the photo. Photo courtesy of Dennis Hammond.  A

rare photograph of the Lamb Inn and Steam Laundry, showing the heart of

the village. Photo courtesy of Dennis Hammond.

A

rare photograph of the Lamb Inn and Steam Laundry, showing the heart of

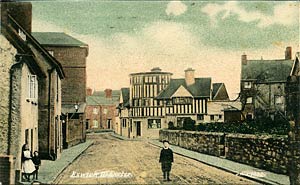

the village. Photo courtesy of Dennis Hammond.  Edwardian Exwick with the

County Steam Laundry on the left and the striking black and white post

office in the centre. Built in 1893 the Post Office, closed in

1966, and has been converted into three houses.

Edwardian Exwick with the

County Steam Laundry on the left and the striking black and white post

office in the centre. Built in 1893 the Post Office, closed in

1966, and has been converted into three houses.

Pubs of Exwick Village

Inn - St Andrews Road

Thatched

House - Foxhayes

The Buller Arms - occupied

one of the brick and cob thatched cottages next to Exwick Mill (the

Steam Laundry site). In 1841 it was known as the Maltsters' Arms, but

by 1844 it was the Buller's Arms. It was closed when in July 1890 the

landlord, John Edward Gilham was found guilty of serving out of hours,

and the license was

revoked. The 1901 Census shows it as a cottage called the Old Buller

Arms with John Blackmore, a miller, in occupation.

The

new concrete bridge across the flood channel, and

the old Station Road bridge built by the Buller's. It was swept away by

the flood the day after this photo was taken in 1974. Photo courtesy of

Alan H Mazonowicz.

The

new concrete bridge across the flood channel, and

the old Station Road bridge built by the Buller's. It was swept away by

the flood the day after this photo was taken in 1974. Photo courtesy of

Alan H Mazonowicz.  The mill pool above the laundry.

Photo courtesy of Alan H Mazonowicz.

The mill pool above the laundry.

Photo courtesy of Alan H Mazonowicz.  A

flooded Exwick leat with Exwick Terrace. Photo courtesy of Alan H

Mazonowicz.

A

flooded Exwick leat with Exwick Terrace. Photo courtesy of Alan H

Mazonowicz.

Notes on Streets and Places of Exwick Foxhayes -

was a small hamlet. The name probably refers to foxes.

Foghays (Voghays) - may refer

to coarse grass or mist.

Rackfield Cottages owned by

Mallet - named after the tenter grounds or rackfields where the woollen

serge was hung to dry.

Hamlyn Lane was once a

packhorse route, and 'coffin-way' to Whitestone, and is believed to be a Saxon field boundary. Named

after the farm which was named after the owner.

Winchester Avenue - was once

the drive to Cleave House

Guys Road - named after Albert

Henry Guy, farmer of Foxhays Farm.

Old Bakery Close - named after

the Mother's Pride bakery that was on the site.

Cleave House - became a centre

for the Guide Dogs for the Blind in 1950. Now residential flats and

apartments

Wearcliffe House - designed by

John Merivale of Barton Place in the early 1800's.

Exwick House - dates to circa

1820/30.

Exwick Manor House - home of

the Russel's, Oliver's and Gibb's families. The site of the Village Inn

was probably the coach house.

The Hermitage - origin may be a

12th Century monastic building and part of Cowick Barton's estate. Part

is 16th and 17th Century and part of the interior is Regency.

Barley House - was fortified by

Fairfax during 1646.

Redhills Hospital - built in

1836 for the St Thomas Union as a County Workhouse. More recently it

was a maternity hospital and old peoples centre. It is now housing.

The

1960's floods hit Exwick Stores. Photo Mike Ewings

The

1960's floods hit Exwick Stores. Photo Mike Ewings

Exwick

School in the floods. Photo Mike Ewings

Exwick

School in the floods. Photo Mike Ewings

│ Top of Page │