The Devon County Gaol at the Castle

1066 to 1795

Page added 3rd July 2016

Return to Public Services

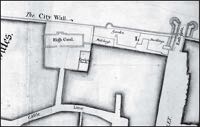

When William the Conqueror took Exeter in 1068, after an eighteen day siege, one of the first things he did was to build a castle and to grant the gaol to William Porto, one of his servants. The wording implies that the gaol already existed, although it would have soon been rebuilt in the Norman manner. There is no evidence to suggest this gaol was other than the one within the walls of the city, just to the south-east of the castle, on the site of what is now the Timepiece.

Henry I granted the keeping of “the common prison within the County of Devon” to John Janitor (his name relates to his job for the King). The gaol was the responsibility of the holder of the manor (in this context the parish of Bradninch that lies around the castle), whereupon it was passed from one owner of the manor to another until the late 18th Century. The last owner of the manor, Lord John Rolle, was released from running the gaol (or appointing someone to run it). The Government conferred the responsibility on to the Justices of the County of Devon. Soon after, in 1787, an Act of Parliament was granted to build a new gaol on “a healthy spot of ground, on an elevated situation, near Danes Castle, being purchased, it was began this year, and completed in about four years.” (Jenkins) It should be noted that the Devon High Gaol was for felons and the St Thomas gaol for Devon debtors.

What was the gaol like?

The new gaol was planned because the city gaol was small, unhealthy and in poor condition. “The County and City Prisons were a disgrace to humanity—mere nuisances and dens of pestilence…” (Rev., George Oliver). Oliver quoted in his History of the City of Exeter, “The county jail lay just below it (the Castle) a living tomb—a sink of filth, pestilence and profligacy,” where several perished from sheer starvation. The Lent or Black Assizes of 1585 were so named because of the gaol fever that swept through the City Gaol and even the judiciary—Mr Serjeant Flowerby, the Assizes judge, eleven of the jury and five magistrates all died of the fever. Gaol fever was typhus, a disease that is transmitted by parasites such as lice, fleas and ticks. The next few Assizes were held elsewhere in the city.

In 1608 the justices of Devon received a complaint “that, by reason of the then dearth of all things, the number of prisoners had greatly increased, and their allowance found was so small that divers of them have perished through wants.” The justices ordered the constables “to be diligent in collecting the money for the gaol, that the poor prisoners do not perish thro’ their default.” Despite the appalling conditions in the gaol, nothing was done, although a new session house was built in the Castle grounds and in use by 1624.

Poor prisoners often had to rely on charity to support them while incarcerated. To this end William Paramore, an Exeter merchant, bequeathed in his will of 22 February, 1570, to needy prisoners, ten shillings annually, to be paid by his heirs, from the income of land in Cook Row, South Street. Elizabeth Seldon, bequeathed sixpence weekly, also to be distributed among poor prisoners. In 1568, Mrs Joan Tuckfield, widow of Mayor Tuckfield left to the Corporation of Tailors,the income from her lands in the parish of St. Paul, so long as they were distributed annually, among the poor prisoners in the Gaol, a sum of two shillings, each Midsummer. She also left funds to keep in repair the wall containing the small cemetery at Gallows Cross.

After the Civil War, during the time of the Commonwealth, there were some who plotted to return the country to the monarchy. One such plot of 1655 to proclaim Charles II as the King, resulted in Colonel John Penruddock, Hugh Groves, [Robert Duke] Richard Reeves, Edward Davy, Thomas Poulton, Edward Willis, Thomas Hillard, John Haynes, James Horsington alias Herish, and John Giles alias Hobbs, being accused of treason. After their conviction they were held at the High Gaol, awaiting execution. Penruddock, Groves and Jones were beheaded on 16 May 1655 and Penruddock buried in St Lawrence Church and Groves in St Sidwell's Chancel. The rest were hanged, drawn and quartered.

I nice description of a riot at the gaol was published in 1793:

"Saturday morning about eleven o'clock, the condemned prisoners in Exeter Goal rose, in the absence of Mr. Sarell the keeper, and attempted to break prison; one of whom had got over the Castle wall, and went down among the people upon Northernhay walk, with his iron hid under a pair of trowsers he wore, but the clinking of his fetter discovered him, and he was secured and brought back; during this time the rest in the goal were committing the greatest outrages, by breaking down the walls, and throwing brick-bats, &c. at those who approached them. Mrs. Sarell narrowly escaped with her life, owing to a large earthen pan being levelled at her by one of the fellows, which providentially missed her. After the riot, and they were confined in the cell, they pulled up the staples, broke a large iron bar, and attempted to dig their way through the wall, but in this also they were discovered and prevented." Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 25 April 1793

After the prisoners were moved out to the new Devon County Gaol in 1795, the old gaol was demolished and replaced by the Congregational Castle Street Chapel, this being the building now occupied by the Timepiece.

Source - The History of the City of Exeter by the Rev.,George Oliver, Civil and Ecclesiastical History of the City of Exeter by Alexander Jenkins and Archaeological Excavation at the Timepiece Nightclub, Little Castle Street, Exeter, January 2011, and Exeter Memories.

│ Top of Page │