Paul Street

Page updated 28th April 2011

Before Queen Street was

cut in 1835, Paul Street could be entered from the bottom of

North Street, at a junction next to the North Gate, or from the top of

Gandy Street. It is known that Gandy Street follows the line that the

Roman guard patrolled inside the city ramparts. The northern side of

Paul Street would have been just inside the northern wall of the

fortress. It was only when the Romans built the wall, that the

boundary of the city extended from a neat rectangle to the larger part

semi-circle it is today. Archaeologists investigated along the wall,

before Habitat was built, in the 1980s, and discovered the traces

of a square tower inside the wall, probably one of a series.

Before Queen Street was

cut in 1835, Paul Street could be entered from the bottom of

North Street, at a junction next to the North Gate, or from the top of

Gandy Street. It is known that Gandy Street follows the line that the

Roman guard patrolled inside the city ramparts. The northern side of

Paul Street would have been just inside the northern wall of the

fortress. It was only when the Romans built the wall, that the

boundary of the city extended from a neat rectangle to the larger part

semi-circle it is today. Archaeologists investigated along the wall,

before Habitat was built, in the 1980s, and discovered the traces

of a square tower inside the wall, probably one of a series.

Benjamin Donn's map of Exeter of 1765 shows the street named Waterbury Lane from the North Street end to Goldsmith Street. From Goldsmith Street to Gandy Lane (Street) it was known as Carey Lane.

From Church to Wishbone Ash

Named after, the pre Norman in origin, St Paul's Church, the street was a mix of houses, tenements and cottages lining the many side alleys and courts, along with small shops and taverns. The church was rebuilt in the second half of the 17th-Century. Always a centre of the community, it became surplus to requirements in the 1920s, and Bishop Cecil ordered it to be demolished in 1936. See Garton & King Video for a shot of the vacated space. During the war, the site was an emergency water-tank and then a temporary building that was used as a British Restaurant. In the 1960s it was a beat club called The Look In. The Empty Vessels, now Wishbone Ash used to play there - but we digress.

During the same excavations that discovered the Roman tower, a mediaeval well was uncovered; the builders had used two barrels, one on top of the other, without bottom or tops, to line the well and prevent earth from falling into the water. The lower of the two was well preserved and found to be made of oak, bound with hoops of hazel. Many houses had private wells before the advent of piped water, while the poor would fill buckets from one of the public fountains around the city. Further excavations uncovered glass and pottery storage jars from 1575/80, one of which was richly decorated with blue, red, yellow and green colours over a white glaze. Some of the jars had contained pharmaceutical potions and lotions which either indicate an apothecary in the street, or a hypochondriac householder.

In the first part of the 18th-Century, Thomas Pennington III, ran a bell foundry in the street. The museum has an example of his work, which is considered to be rather rough and ready; the bell bears the letters T and P, with an inscription 'THE . COUNTY. OF. DEVON. 1718'. It is thought that it may have been cast for use at the County Prison, being deliberately given a rather tuneless, or distressed tone, to be tolled at an execution or the escape of a prisoner.

Medical Men

Some five years after the bell foundry cast the prison bell, John Patch Jn, was born in Paul Street, in 1723. His father, also named John Patch, joined the Devon and Exeter Hospital in 1742 as senior surgeon, while Patch the younger, was appointed a surgeon in the same year, at the precocious age of 18. John Patch Jn., died in 1787 and was buried in a family vault within St. Paul's Church.

Paul Street seems to have been conducive to the medical profession, for John Blackall, physician, was born in the street in 1771. He was elected to the Devon and Exeter Hospital in 1807, and became an expert in dropsy, for the first time linking it with kidney disease. He was famous for his skill in diagnosis, based on careful clinical examination. He died at Southernhay, in 1860, at the age of 89.

The 19th-Century

In the early 19th-Century, before the advent of the railway, Falmouth was used as a port for landing mail from England's growing overseas interests. Mail would be landed and a post chaise and four horses despatched to take it to London. Important Government correspondence would often be sent on horseback. The contractor in Exeter, as a relay town, was Mr. Mugford of Paul Street, who was based in Athelstan Court, situated at the modern entrance to Habitat. Here, a man and horse was constantly at ready, day and night, to carry the mail on to Honiton, if bound for London, or Crockernwell, if bound for Falmouth.

Although the upper end of Paul Street was joined at right angles to Gandy Street, the main entrance to the street was from the bottom of North Street. Paul Street in the early 19th-Century was mostly private houses belonging to professional men. Away from the leats, and as a street of merchants and professional men, the water supply for Paul Street would have been from private wells, with some individuals paying for piped water from the water-engine. As a consequence only four deaths were recorded in Paul Street during the 1832 cholera outbreak.

On the northern side of the street, a few doors down from the junction with Queen Street there was a school run by Mr. Trueman. In front of this house there were iron posts and a chain fixed on the kerb, which presumably prevented the unruly schoolboys from spilling out of the front door and into the street, lest they be mown over by a passing pack horse or wagon. Later on, through the century, the school became the South Western Hotel run by Mr H Elmore. Between 1840 and 1843, the West of England Institute for the Instruction and Employment of the Blind, was housed in premises in Paul Street before it moved to St David's Hill.

On the opposite side of Queen Street, off Little Paul Street, a number of old houses, that had an entrance from Paul Street, were demolished to make way for the Royal Albert Memorial Museum. The Museum Hotel, opened in September 1868, at the height of the 'museum mania'. It was situated on the corner of Paul Street and Queen Street, where the modern Chandni Chowk now trades. In November 1871 the "Exeter City Cricket Club spent Monday evening most harmoniously at the Museum Hotel".

The Tunnel

The modern Pitcher and Piano, formerly Chumleys was a wine and spirit merchant run by Mr Crockett in the early 19th century. In 1852, he sold out to Harding and Richards, of St Anne's Well Brewery. The business used cellars beneath the building and across Little Paul Street. When the museum was built, the cellars were preserved, and a tunnel was built that crossed under Little Paul Street, linking the two sets of cellars. A stone was placed with the inscription, "This tunnel was built on the construction of the Albert Museum 1869 by Harding Richards, Wine Merchants". The tunnel was eventually bricked up, and Harding and Richards, reverted to using the cellars below the shop.

William Widgery, the artist, is listed in 1885, sharing a workshop in Athelstans Court with Joseph Albert Collings veterinary surgeon. Widgery often produced large canvasses for hotels and even the Theatre Royal, requiring a large space to work, unlike his son, F J Widgery who preferred painting small Dartmoor landscapes in gouache. The Rougemont Hotel has several examples of William Widgery's work hanging in its public rooms.

The impresario and discoverer of Charlie Chaplin, Fred Karno was born in Paul Street on 26th March 1866, with the name Frederick John Westcott. His family moved to Nottingham when he was nine years old, but he never forgot his Devon roots and often said "Devon born and proud of it".

The 20th-Century

By the turn of the 20th-Century, Paul Street was becoming rather run down. The housing was no longer the abode of the professional class, and there were twelve or so narrow alleys and courtyards running off at right angles from the street as far as the city walls. Probably the most well known of all is Maddocks Row, eight buildings between Paul Street and the wall, which still leaves traces via an arched opening through the city wall to Northernhay Street. In the 16th century it was known as Murally Lane. For many years, it was where the Mayor, in procession with civic dignitaries, would mount the wall for his annual tour of inspection. E T Fulford the auctioneer and appraiser, and forerunner of the modern estate agents, was based in Maddocks Row in the latter half of the 19th-Century.

Walter Daw, who was Mayor in 1963, and again, for one day, in 1974 was born in the street in 1905. His father ran a bakery business. The church was the centre of his life as he grew up, and organisations such as the Boys Brigade and the choir were there to guide the offspring of the small traders in the street.

On the opposite side could be found Goldsmith Street and Pancras Lane, linking Paul Street with the High Street. The distance between the parallel High Street and Paul Street is perhaps 200 metres, and yet the two streets could have been 200 miles apart. The High Street was cosmopolitan, busy, the centre of fashionable Exeter, while Paul Street was provincial, self contained and very local.

Like every other street in central Exeter, Paul Street was well provided with public houses. The Anchor Inn on the corner of Maddocks Row was first listed in 1816. It was one of the first buildings to be considered for demolition for road widening, when the City Council paid £300 to purchase the premises in 1906. An even earlier inn was the Blue Anchor that was mentioned in two adverts in the Flying Post in 1799.

Other public houses of note included the Crediton Inn on the corner of North Street, which was trading from at least 1811. In 1870, the Rational Sick and Burial Society Society opened a branch at the Crediton Inn, but it didn't save the house from closing in 1913. The King William was open for a few years in the middle of the 19th-Century and the Lord Nelson, listed between 1816 and 1830.

The Demolition

During the first decade of the 20th-Century, Exeter undertook a series of schemes to modernise - electricity was introduced allowing an electric tram system and a new bridge to be built. The first public housing was built in Isca Road and the pressure on the council to improve living conditions for the poor increased. The advent of the motor car meant that streets needed to be improved and widened. The first signs of action have already been mentioned with the purchase of the Anchor Inn for road widening. The High Street and South Street were also losing buildings in an effort to widen the thoroughfare. It wasn't until 1920 that serious work started in Paul Street to clear out the slums and rehouse the people. Over a period of five or so years, almost all the houses and businesses in the rectangle between the city wall and Paul Street were demolished, without very much idea of what would replace it. The London and South Western Hotel was closed in September 1924 to be demolished, while the Museum Hotel was demolished in 1926.

As car ownership grew, the need for parking became apparent, and the waste ground that was so recently a thriving community became a car park; Athelstan Court, Maddocks Row through to Cornish Court and Arthur's Place became home for the rubber wheeled, infernal combustion machine. When the tram system was closed in favour of the motor bus, the eastern end of the cleared area became the Paul Street bus station - it would in later years take up all of the old area between the street and the wall, and would be the coach tourists first view of our city. A small, mock Tudor, timber framed building appeared on the corner of Paul Street and Queen Street, housing the Official Information Bureau where the passing tourist could find a hotel, or directions to the Cathedral.

By the time St Paul's Church was demolished in 1936, the heart of the community was long gone. No longer a thriving local community, the street remained busy as many local and long distance buses used the bus station, and the carpark filled and emptied, according to the rhythm of the shopper. After the Second War it became apparent that the bus station was badly sited and overcrowded, and in 1964, it was moved to a new site off Paris Street.

By the 1970s, the City Council was making plans to redevelop the area behind the Guildhall as far as Paul Street. After a campaign by W G Hoskins and others, the Higher Market was saved and incorporated into the design, but all the buildings on the south side of Paul Street were demolished, including the last pub in the street, the North Devon Inn, to be replaced by a slab sided edifice, whose only function was to hide the shopping centre and yet, more parking. With the building of the Harlequins Centre, the process of change from thriving community, 70 years before, to a slab sided canyon of red brick and composite façade was complete.

World War One Dead - Paul Street

Private,

Sidney Back, Devonshire Regiment. 13 January 1915. Age 29. Barbican

Place, Paul St

Serjeant, Henry Norman Stares, Worcestershire

Regiment. 16 November 1918. Age 31. Maddocks Row, Paul St

Sources - Trewman's Exeter Flying Post, James Cossins, Reminiscences on Exeter 50 Years Past, varous street directories, Wikipedia, Devon Records Office and the West Country Studies Library.

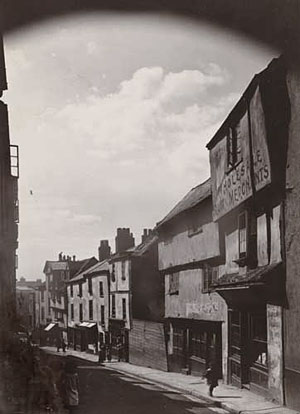

Looking down Paul Street in 1911. The

buildings on the right are now the site of Harlequins. Courtesy of the

West Country Studies Library.

Looking down Paul Street in 1911. The

buildings on the right are now the site of Harlequins. Courtesy of the

West Country Studies Library. Looking down Paul Street in 1926 after

the right hand side was demolished. It would become the bus station and

then Harlequins. St Pauls Church is extreme left. Courtesy of the West

Country Studies Library.

Looking down Paul Street in 1926 after

the right hand side was demolished. It would become the bus station and

then Harlequins. St Pauls Church is extreme left. Courtesy of the West

Country Studies Library. The

age of the car park has arrived in Paul Street - 1950s. Photo Express

and Echo.

The

age of the car park has arrived in Paul Street - 1950s. Photo Express

and Echo. A view down Paul Street before the

Golden Heart project destroyed the southern side. The Official

Information Bureau is right - circa 1965. Photo Jim Billsborough.

A view down Paul Street before the

Golden Heart project destroyed the southern side. The Official

Information Bureau is right - circa 1965. Photo Jim Billsborough. The charming little Paul Street - is

this what we really want our city to look like?

Photo David Cornforth.

The charming little Paul Street - is

this what we really want our city to look like?

Photo David Cornforth.

Anchor Inn

Blue Anchor Inn

Crediton Inn

King William

Lord Nelson

Museum Hotel

North Devon Inn

Pitcher and Piano - Little Paul Street

South Western Hotel - Queen Street corner

The Exeter Pictorial Record Society was founded in 1910. It collected a number of photographs of the various courts and places off Paul Street. See the Exeter Pictorial Record Society page on the Devon Libraries Local Studies site, where there are many photographs and illustrations of the city at the turn of the 20th-Century.

│ Top of Page │