- Home

- Memories

- Scrapbook ▽

- Topics ▽

- People ▽

- Events

- Photos

- Site Map

- Timeline

Page updated 9th August 2011

Return to Service Industry

Also see - Water

Carriers of Exeter

From Roman times Exeter had relied on springs and wells to supply water to the city. The Romans had built wooden aqueducts to carry the water into their settlement, while in the 13th century, the Cathedral authorities built the first underground, piped water system. See Underground Passages for more on this system.

By the early 17th century, the existing water supplies were becoming inadequate for the city, whose population grew from 8,000 in the early 17th century to 15,000 in the 1690s. In 1694, the Corporation secured an Act of Parliament to improve the water supply to the city. They engaged three men from Stourbridge, Jonathan Pyrke, an engineer, Richard Lowbridge and Ambrose Crowley, along with Daniel Dannel from Gloucester to build a water engine on the Exe to pump water into the city. They chose to install the water engine, which was a large water wheel attached to a pump, in the New Mill Leat just above where the Longbrook stream joined the watercourse. The leat was fed with water from the river by the Head Weir. The four were given a lease of 200 years, at a rent of 5 shillings a year.

A building was constructed at the rear of the Guildhall, that would be known as the Back Grate for the lead lined water cistern, measuring 28 ft by 18 ft, The partnership had to ensure that the gaol beneath the tank was maintained for the custody of prisoners.

Celia Fiennes wrote a few years after the tank was completed, that it could contain 600 hogshead (31,500 gallons) of water. Permission was granted to dig trenches along the valley of the Longbrook into the city to take the 18 inch (45 cms) diameter elm-log pipes which could supply a stream or pillar of water, 7 inches (18 cms) in diameter.

By 1735, Richard Haddy, a relative of Lowbridge, who had a controlling interest in the company, also rented some old cottages next to the wheel for a half guinea a year, which were used to extend the works.

A second cistern at Northernhay was installed a few years after the water system commenced operation, but by 1807 it was listed as having been out of repair for several years.

Once the water was in the cistern, it was delivered to local households by water carriers in buckets; they would charge to deliver water per quarter, or per bucket. They floated wood on the surface of the water to prevent loss through splashing. The cisterns were not the only sources of water in the city and some water carriers used horses or donkeys to pull a barrel mounted on a cart and would supply the lower parts of the city, around Exe Island and the West Quarter with water taken directly from the river. In addition, there were public supplies through the carfax at the junction of Fore Street and the High Street, and another supply further up the High Street.

James Golsworthy

Towards the end of the 18th century, the water supply from the

water-engine was in need of improvement, with leaking pipes and

stoppages during floods or drought. Around about 1808, a locally born

machine-maker, James Golsworthy, was engaged as manager of the water

works. He immediately set about improving the system, with a more

reliable pump attached to the wheel, and replacing the wooden pipes

with 6 ft (180 cms) cast iron pipes from Chesterfield. Cast iron pipes

had first been used in England in 1746.

The new pipes reduced leakage, but it would not be for another 50 or 60

years before a reliable method of joining them would be devised, that

would prevent leakage all together. In 1827, Golsworthy purchased

Priory House off

Mary Arches Street, now St Olaves Hotel to live in; on a

garden

wall can be found

an inscription from the original water works that reads:

THIS WATER WORKS WAS

CONTRIVED BY AMB. CROWLEY

AND DAN. DANNELL A.D. 1694

IMPROVED AND REBUILT BY

JAMES GOLSWORTHY AD 1811

Some prominent citizens urged Golsworthy to build a holding reservoir in Pennsylvania at Marypole Head to improve the supply to St Sidwell's and St Leonard's and ensure that the existing fire plugs would be reliable when called upon. Golsworthy insisted that his system was already adequate for the job. It would be the 1832 cholera outbreak that would resurrect the idea for a holding reservoir for the city.

In 1822, Golsworthy purchased a quarter share in the water company from the widow of Richard Pyrke, a descendant of one of the original four shareholders for the sum of £700. In August of the same year he acquired the remaining 75% of the shares from a Mrs Rouse for £2,300, making him the sole owner of the concern. In 1828 he sold a quarter share to Charles Wheaton for £2,300, making a handsome profit.

Then as now, the public water supply was a monopoly which could return handsome profits for the owner. In 1824, he charged 30s for 4 hogsheads of water to a household and 12s extra for a water closet. In the early 1830's, 400 out of 4,000 houses were connected to Golsworthy's system - people wanted a water supply, but were reluctant to pay for it.

The insurance companies paid Golsworthy £300 to install fireplugs and supply water for fire fighting. These same plugs were also used to swill the streets with water to cleanse them. Even in the early years of the 20th century, the water was turned on to clean Smythen Street and Stepcote Hill.

Not everyone welcomed Golsworthy's water engine and a chilling letter from someone going by the name of Swing was published in the 4th January 1831 issue of the Flying Post.

"GOLSWORTHY– This is to inform you that you and your water-works being the pest of the City of Exeter not only by taking bread out of the mouths of the poor watermen but by your overbearance and pride this is to inform you that if you do not destroy that vile machine of yours that in 9 days it shall burnt to the ground and further if you neglect this notice you shall not only have your property burnt but a mark shall be made of your body From your deadly enemy "SWING""

No attempt was made by Golsworthy to process the water in any way, and thus clean it, and it was only a matter of time before a water borne disease would visit the city, although ironically it would not be his system at fault.

Cholera

strikes

In 1832 a woman visiting from Plymouth was taken ill in North Street

and died very quickly from cholera. This case and subsequent cases

contaminated the inadequate

sewage system, which in turn contaminated the water supply. But which

water supply had been contaminated. Was it the water supplied by the

mediaeval passages from St Sidwell's and which supplied the carfax, or

was it the private wells in the city, or water from

Golsworthy's water engine? Research by A J Killingback suggests that it

was none of these, but rather it was water dipped by the water carriers

from the upper and lower leats at Horsepool and the steps by Cricklepit

that caused the disease to sweep the West Quarter. The contention is

that contaminated water from sewage reached the Longbrook which flowed

into the leat just below Golsworthy's

water engine. The water supply from the water works was taken from

river water

above the Longbrook and could not be responsible.

A New Water Works

The four month outbreak killed 440 people, most of whom were in the

poor parts of Exeter, and it was this tragedy that forced pressure from

concerned citizens for the city to negotiate

with Golsworthy for him to sell his business to a new company - it was

no longer thought appropriate for an individual to control such an

important commodity. Golsworthy obtained an Act of Parliament to extend

and improve his own works in the face of this opposition.

The Exeter Water Company was formed in February 1833 in St Sidwell's, with a committee of prominent citizens. An Act of Parliament, to build a water supply system that could supply Heavitree, St Leonard's, St Thomas and St David's as well as the city was obtained and a system of water rates was devised based on the annual rental value of a property. After negotiations, Golsworthy agreed to transfer his lease to the new company. Thought was put to where the water should be drawn to supply the city - one idea was to build a dam across a stream in Whitestone and pipe the water in via Newton St Cyres.

In the event, it was decided to draw the water from the Exe through a new works at Pynes, above the Duryard Mills site, on land belonging to Sir Stafford Northcote. Work was quickly progressed, and by 1835, Golsworthy's water engine ceased operation and was converted into a grist mill. The cistern at the rear of the Guildhall was made redundant and between 1833 and 1840, a new holding reservoir at Danes Castle was constructed. Measuring 200 by 200 ft, and with a depth of 17 ft, it had a capacity of 315,000 gallons.

The Pynes water works was initially worked with a water wheel, similar to Golsworthy's wheel at engine bridge, and could supply 438 gallons a minute to the Danes Reservoir which was 150ft above sea level, from three pumps. A second wheel was installed in 1841 to keep up with demand, which was more able to cope with backflow during flood conditions. In the same year, 3,400 houses had a water supply from Pynes out of 5,122 in the city. The water supply was vastly improved from that of Golsworthy, but the supply was only available for three hours daily, three days a week. It was estimated by Thomas Shapter in 1841 that 98% of families who drew water from the works, had water in their houses, with a barrel or small cask sitting in a corner, filled from a ball-cock regulated pipe. All the same, only about a third of households had a supply of water to the house, according to Shapter.

By 1850, 12 miles of iron pipes had been installed allowing the provision of public baths and water fountains. In 1856, a steam engine was installed at Pynes to pump the water.

In 1867, St Thomas, which had been supplied from the Danes Castle Reservoir, sunk a well in Buller Road and used a steam engine to raise the water, which was held in its own reservoir in Dunsford Road. The Marypole Head Reservoir was built in 1873 at Higher Hoopern to supply households above Danes Castle. However, the company could still only supply water on an intermittent basis, and Thursdays there was no water supply.

After the 1875 Public Health Act, the City Council worked to improve the quality of the water, and to this end, they acquired the shares of the Exeter Water Company in 1877 for £116,416. At the same time, they took over the Dartmoor and Exeter Water Company, which had been formed to build a reservoir near Sticklepath.

Various improvements have been made over the years to Exeter's water supply, with additional holding reservoirs and hundreds of miles of pipe. In 1935, Exminster, Shillingford, Ide, Upton Pyne, Brampford Speke, Stoke Canon, Huxham, Poltimore, Clyst Honiton, Sowton, Clyst St Mary and Broadclyst and Topsham were added to the city supply. In October 1964, the Exeter City Water Undertaking was absorbed into the East Devon Water Board. Privatisation occurred in 1989, with the creation of South West Water.

Source: Life to the City by Walter Minchinton and James Golsworthy and the Exeter City Water Supply During the 1832 Cholera Epidemic (Transactions of the Devonshire Association) Alan John Killingback and the Flying Post.

On an external wall of

St Olaves

Hotel on Mary Arches Street there is a

drinking fountain which was installed by Golsworthy in 1839

On an external wall of

St Olaves

Hotel on Mary Arches Street there is a

drinking fountain which was installed by Golsworthy in 1839

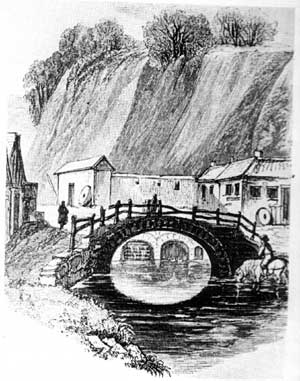

The water engine was below the cliffs of Mount Dinham, just above Exe

Street.

The water engine was below the cliffs of Mount Dinham, just above Exe

Street.

The city cistern was built over the cells at the rear of the Guildhall.

The city cistern was built over the cells at the rear of the Guildhall.

The water carriers felt their living threatened by Golsworthy.

The water carriers felt their living threatened by Golsworthy.

│ Top of Page │