A history of the City of Exeter Police Force

Page updated 2nd February 2018

Back to Public Services

Also see Police Officers 1919 - 1966

Police Officers of the 19th-Century

Before the advent of policing in the United Kingdom, it was the job of the Mayor and Aldermen, as magistrates, to dispense penalties to those who broke the law. They relied upon constables, quite often the sergeants-at-mace that had existed from 1285, night watchmen who were paid to patrol the streets and merchants and other men of property who were required from time to time to act as unpaid special constables, to enforce the law and detain miscreants. The whole system was inefficient, and chaotic, often allowing anti-social behaviour and crime to flourish in the streets of every community in the country.

So, at the turn of the 19th-Century, Exeter relied on four sergeants-at-mace and four staff-bearers and 44 others, all sworn in as constables. The sergeant-at-mace were mostly responsible for running the courts and warrants as directed by the magistrates, while the staff-bearers served summonses, attended the mayor and were responsible for the care of the Guildhall.

From 1810, at night, the city had a Captain of the Watch with three inspectors and eight watchmen, all paid, by the Improvement Commission. In 1832, a private act to improve paving, lighting, watching, cleansing and generally improving the city of Exeter was passed. The act defined the role of the watch more precisely, giving them the power to arrest people who were "Felons, Malefactors, Vagrants, Beggars, Disturbers of the Peace.... or loitering in groups and not giving a satisfactory account of themselves." Special Constables were created with an act in 1832, to supplant the merchants and men of property who in former times had to work as unpaid special constables as part of their civic duty.

The Watch Committee

After the Reform Act of 1833 which attempted to insert a degree of democratic accountability into local government, the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 reorganised city councils. One of the requirements that the act addressed was that of policing, with the introduction of the Watch Committee, manned by councillors, who were responsible to ensure discipline, authorise the payment of salaries from city funds and appoint a Superintendent of Police to oversee the police force.

Exeter's first Superintendent was Captain Hugh Cumming, who was appointed in 1836. Cumming had been the city's unpaid sword bearer from 1830, a position which he continued to hold for a few months, before it was abolished, leaving him the task of organising a system of police for the city. He became the head of a force of twenty-seven officers and men on a salary of £120 per year.

The day force consisted of two sergeants-at-arms and six staff-bearers, while there were twelve night watchmen, four-inspectors and a captain of the night watch. The uniform consisted of "greatcoats, capes, boots and patent leather girdles with strong white-metal buckles", with silver lace decoration. In addition, the constable carried a rattle, lance wood stave, lantern and handcuffs.

Cummings tenure was not altogether successful, for in his eleven years in charge, sixty-one men were dismissed from the force, many for drunkenness, fighting or absence without permission.

The Watch Committee had had enough by 1847, and after an acrimonious fight over the terms of Cummings pension, they appointed a young 29 year old, David Steele as the Superintendent. Steele set about reforming the force, removing many of the traditional practices that were a hangover from former times, and making sure that the new Acts of Parliament that related to policing and public order were efficiently introduced.

His force consisted of twenty-nine men, eleven of whom were employed in the day and the rest between 9pm and 6 am. There were 120 public houses in Exeter at this time, along with the many beer-houses that had opened since the 1834 Beerhouse Act; drunkenness was rife among the population, causing in its wake, many other crimes.

Superintendent Steele introduced fines for the police officer who failed to wear his uniform, or was slovenly in manner, or had failed to inform the Superintendent of information regarding a robbery of other crime. A Police Medical Officer was appointed, and the men had to pay into a sick club, to which the City Council contributed £5 per year. In short, a police officer had to be professional in his job, for which he received improved conditions.

As mentioned,

drunkenness was rife, and the Vagrancy Act was introduced to reduce

begging and petty crime. The prison in Queen Street was designed for

short sentences, and any criminal who committed a more serious crime

would often be transported to a penal settlement in Australia, or for

murder, be hung.

In 1861, Superintendent Steele introduced 24 hours

of leave, per month, for each constable, and in 1863, when the Prince

of Wales was married, a dinner was given for sergeants and constables

in celebration. Each office was presented with a "Rosette of Ribbon" at a cost of no

more than sixpence each. Pay was increased, for a constable, after one

year in the force to 19s, and by 1867, the strength of the force had

increased to forty-four men.

In with the helmet

The cape was abandoned, to be replaced with a swallow-tailed coat with large metal buttons, Wellington boots and a wide leather belt. In 1873, the top-hat with a shining crown was replaced with the police helmet, the swallow-tailed coats shortened, and leather Blucher half-boots replaced the old Wellington boots.

Superintendent Steele's reforms worked well, but by the late 1860s, it was apparent that he was behind the times, and that the Police Force in the city was starting to have problems, so in 1873, he retired.

The new head of the police was Captain Thomas Bent, formerly of the Royal Marine Light Infantry. The first to be known as Chief Constable, Bent had recently been chairman of the St Leonard's Ward Conservative Association, and was appointed by a majority of the Watch Committee that was dominated by Conservatives.

Bent immediately requested an increase in the size of the force to 50 officers, including three sergeants and, for the first time, detectives. He also introduced a more military approach to running his force, with twice weekly drill and sick pay for officers, unless their illness was caused by vice or intemperance. He wanted a physically fit force, and agreed to personally pay for any cod liver oil that was ordered by the Police Surgeon. Each man on night duty would also be provided with a pint of coffee to dissuade them from wandering off, looking for a drink elsewhere.

In 1875, the Chief Constable was still based in a small room in the Guildhall. Bent requested an allowance for a larger room, and he moved into the first floor of 59 High Street.

St Leonard's was incorporated into the city during 1878, and police strength increased to 62. In the same year whistles replaced the rattle, and annual leave was introduced. Six years later, and the pocket book was introduced, indicating a better educated and more literate policeman.

The next year, the police were called to the Princess Alexandra Inn on the Bonhay Road as the dismembered body of a baby had been found in the leat at Powhays Mill. Closely followed by journalists from across the country, the police soon tracked down the mother of the child, and a woman named Annie Tooke, a child minder from South Street. They charged Annie Tooke with the murder, using forensic evidence to prove her crime, for which she was hung.

A Disgraced Chief Constable

Chief Constable Bent did not have an easy ride in charge of the force, as he became increasingly accident prone. Two years after he was appointed, he was implicated in an encounter with a prostitute in London, when he was brought up before a magistrate in Marlborough Street. In 1880, damages and costs were awarded against him in a case of malicious prosecution and false imprisonment. A meeting with Bishop Temple to discuss Sunday closing, during 1882, was broken up by a crowd of ruffians; Bent's tardiness in dealing with the incident required the mayor to be summoned. This was a time when the council was dominated by brewers and licensed victuallers.

Chief Constable Bent was accused, after a fire in 1883, of preventing the employees of a firm from entering the burning building to save a number of carriages. He was summoned on several occasions for showing disrespect towards the mayor and town clerk and in 1885 he was suspended for 'reprehensible behaviour.' In addition, there had been several dismissals from the force for drunkenness for which he was held to account. Despite a favourable Government Inspection in 1885, Bent took 14-days leave of absence on a doctor's certificate, and then tendered his resignation.

Theatre Royal Fire

After a delay, covered by a temporary appointment, Captain Edward M Showers was appointed Chief Constable in 1886. Although in office for only two years, his tenure saw the worst civil tragedy in Exeter's history, when the Theatre Royal burnt down in September 1887, killing 188 people, and the opening of the new police station in Waterbeer Street the following year.

In July 1888, Detective Sergeant Harry Brooke le Mesurier, aged 28, was appointed Chief Constable form the Metropolitan Police.

The new police station was connected by telephone to the County Police Headquarters at New North Road in 1888, and by 1890 police strength fell to 56. Drunkenness across the city was still rife at this time, and le Mesurier was asked to furnish the Watch Committee with a quarterly report on the problem, an early manifestation of increased paperwork. Chief Constable le Mesurier was an ambitious man, and in 1893 he was appointed Chief Constable of Portsmouth.

Le Mesurier was succeeded by John Short, an officer who had come through the City Police ranks. Times were changing, and electricity reached the Waterbeer Street Police Station in 1894, the first motor cars appeared in the city in 1896, and the City Police Force took delivery of its first bicycle in 1899.

In 1900, the St Thomas force, formerly a part of the Devon Constabulary, was incorporated into Exeter, increasing the City's force by one sergeant and six constables. In the same year, 127 crimes were reported and 161 cases of drunkenness.

A New Century

Chief Constable Short brought some stability to the service, but in June 1901 he resigned, to be replaced by Richard Llewellyn Williams, previously Superintendent at Chudleigh in the Devon Constabulary.

Changing times and changing conditions were addressed by Chief Constable Williams when he purchased gym equipment for his men in 1904 - dumb-bells, indian clubs and boxing-gloves, along with dominoes, draughts and a bagatelle table for their relaxation. And with the increase in motor cars, trucks and electric trams, the average policeman probably needed some recreational time. Strangely, the demise of horse transport saw the formation of a mounted branch, mostly for ceremonial purposes, which in the 1930s consisted of two sergeants and twelve constables. Williams allowed a St John's Ambulance Brigade to be formed in 1901, which, apart from the First War, remained part of the force's activities.

Forensics were becoming more important, and in 1904, equipment for taking finger-prints was purchased at a cost of 12s 6d. Williams had a miniature rifle range built in 1907 in the police yard, which with the military rivalry then showing in Europe, proved to be a far-sighted move.

The City Police sent officers to Tonypandy in 1911 to help deal with a miners strike, a request that would be repeated through the 20th-Century. This was one of Chief Constable Williams last actions for he died in office in September 1911.

Eric Hubert de Schmid was appointed from the Devon County Constabulary as Chief Constable, having joined the force in 1908. It was a very short lived appointment - January 1912 to April 1913, as he quickly moved on to be Chief Constable of Carlisle.

In 1913, Arthur F Nicholson replaced de Schmid, and Heavitree was annexed and incorporated into the city as the force grew to 78 men. There were now 186 public houses in the city, but as war approached, the number of vagrants plunged; in 1910, 5,004 were dealt with by the City Police, and 2,115 in 1913.

The First World War

When war broke out in August 1914, 35 officers of the City Police Force joined the armed forces and temporary appointments were made to fill the gaps. Twenty four of the temporary appointments also went to the front, and even the Chief Constable applied for the forces, but was twice turned down. New duties were undertaken including controlling aliens, guarding sensitive installations and above all, controlling the many injured servicemen, who were staying at one of the five VA hospitals in the city.

Special constables were appointed by the Mayor, when in 1914, they came under the control of the Chief Constable, adding welcome manpower to the City Police Force.

Exeter police who were awarded medals

during the First World War

Ex-Constable Wilfred Hammond - Medal

of St George

from the Emperor of Russia.

Ex-Constable Townhill - mentioned in

despatches.

Ex-constable Rounsley - received the Meritorious Service

Medal

Ex-constable Barrett - Military Medal

Walter James Clarke,

Percy Ellis and Wilfred Hammond were killed in action.

England was a very different place after the war. Women had found a new freedom to work, and when the men returned from the front, they expected their old jobs back. Unfortunately, many were left unemployed to become vagrants, and inflation increased the cost of living.

Traffic congestion increased and in 1920, a census found a peak average of 842 motor vehicles, horse drawn carts and bicycles passing one census point. Police boxes were introduced in 1925 and traffic lights in 1929. The General Strike of 1926 brought new duties for the police, and Exeter officers had their leave suspended while 126 registered to become special constables.

Death of a Constable

In 1929, 29 year old PC Woollacott was killed when a bus skidded on snow at Exe Bridge, which ran him over. He was the only policeman killed while serving in the Exeter City Police during peacetime.

Chief Constable Nicholson was awarded an OBE in 1924 and the King's Police Medal for distinguished service in 1930. He resigned in the same year and accidentally died of carbon monoxide poisoning in 1938.

The next Chief Constable was 34 year old Frederick Tarry MM, who was appointed in January 1931. He brought a new professionalism to the post, and is still remembered for his book, The Police, a complete handbook for a prospective recruit and for new constables. It covered the qualifications needed to get into the force, plus chapters on the history, probation and training, police procedures and points of law. He emphasised the importance of physical fitness for a policeman. In 1936, Exeter's force was ranked 62 in size for Borough forces with a total strength of 81.

In 1933, Exeter purchased a police van, FJ8300, and light motorcycle for patrol work, while police pillars with a phone and light on the top were installed in 1935. Solving crime was an important aspect of police work, and detectives were sent to New Scotland Yard to learn the latest techniques.

The old Danish Bacon Factory in Waterbeer Street was acquired for additional office space, parades, and the C.I.D. darkroom. See the film Garton and King for views of the police station in 1935.

The Second World War

The clouds of war loomed yet again, and the country braced itself for the new conflict. The threat from bombing affected all communities, although it was thought Exeter was a less likely target.

Chief Constable Tarry was seconded to Southampton in 1940 and in October 1941, Superintendent Rowsell became the new Chief Constable, having held the post as a temporary appointment from 1940. Rowsell had served in the First War, being awarded the Military Medal, before joining the Exeter Police Force in 1919.

The blitz of April and May 1942 saw all the services under immense pressure and Special Constable Harold Luxton was killed in Sidwell Street during the bombing of the 4th May.

Out of the thirty members of Exeter's force that joined up, two never returned, killed in action as flying crew.

Exeter Police killed in action 1939 - 1945:

Constable Hawken - 19

March 1944

Constable Richards - 13 August 1944

Exeter Police who were awarded medals

during the Second World War

Chief Constable Rowsell - O.B.E.

Chief Inspector

Manders - B.E.M.

Sergeant Fraser - Commendation by George VI

Police

War Reserve Constable Hutchings - George Medal

Police Auxiliary

Messenger Reynolds - Commendation

Captain R W Townsend MC - M.B.E.

Nineteen others were commended for their action during the bombing of the city.

In 1944, a VHF radio transmitter was installed at Marypole Head by the Devon County Constabulary, allowing Exeter's police vehicles, that were close enough, to remain in contact with the station at Waterbeer Street.

Also in 1944, the first five police women constables were recruited, two from the armed forces, although they were war reserve, and never in the civilian force after hostilities ended. The first police woman to be recruited was PW1 Phyllis Wooldridge in 1949. In January 1946, the 999 emergency number was introduced so the police and emergency services could concentrate on providing a faster response to incidents.

Five years of war had left the nation tired and dispirited, apart from a small band of racketeers who saw this as an opportunity - with rationing still in force the black market flourished, with con men praying on returning servicemen with scams to relieve them of their savings. The police had to be on their toes to cope with this level of crime.

On Saturday 1 July 1950, a silver altar cross weighing 50 kilos, and valued at £20,000, was stolen from the Cathedral. It was found abandoned in a field at Fenny Bridges, minus the diamonds and other gems, that had been prised off the surface. A week later, Charles E Ware and Son of Richmond Road offered a £450 reward for the diamonds in an advert in the Times. A stolen car was traced to London, but the perpetrators were never caught.

Through the 1950s, some city police officers purchased their own houses, and 41 police houses were built to house the growing force.

After 16 years in charge, Chief Constable Rowsell was seconded to Brighton in 1957, and was replaced by Mr Kenwyn E Steer. Change was afoot, as a new headquarters was completed in Heavitree Road, and the Waterbeer Street premises vacated in September 1959. The next year, and the force, along with the emergency services were at full stretch as large parts of St Thomas, Alphington and Exwick suffered devastating flooding twice within two months. During the first flood, an operations room was set up at the Heavitree police station which maintained six on duty, through the night, and a mobile headquarters established at Exe Bridge.

A lost Force

A Royal Commission in 1962 reported that the country's police forces should be amalgamated into larger, more efficient units. The 1964 Police Act decided that 49 shoud be the appropriate number of Police Forces in England and Wales by the middle of the 1960s. City council run police forces would merge with larger county constabularies, and in some cases, these would merge with adjacent counties to form a large constabulary.

Thus we come to the end of this history of the Exeter City Police Force, as it became the Exeter City Division of the Devon and Exeter Constabulary on 1 April 1966. This was a short lived force for, in June 1967, further mergers created the Devon and Cornwall Constabulary and the last vestige of an independent police force for the City of Exeter disappeared forever, as it passed out of the control and funding of Exeter City Council—Semper Fidelis

Source: Exeter City Police 1836 to 1966 by K J Mallett, the Police by Frederick Tarry,Victorian Exeter by Robert Newman, the Times, Peter Hinchcliffe and Trewman's Exeter Flying Post.

Chief Constable John

Short - 1893 to

1901

Chief Constable John

Short - 1893 to

1901

Chief Constable

Eric Hubert de

Schmid 1912 to 1913.

Chief Constable

Eric Hubert de

Schmid 1912 to 1913.

Funeral of PC

Woollacott in

1929.

Funeral of PC

Woollacott in

1929.

The original

Police-box on Exe Bridge dated from about 1925.

The original

Police-box on Exe Bridge dated from about 1925.

Learning point

duty from Chief

Constable Frederick Tarry's book, The

Police.

Learning point

duty from Chief

Constable Frederick Tarry's book, The

Police.

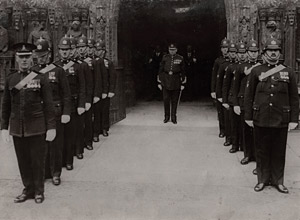

Police line up

outside Exeter Cathedral - 1930s.

Police line up

outside Exeter Cathedral - 1930s.

Police

constables on parade in the old bacon-factory in 1959. They are

inspected by Frederick Tarry, former Chief Constable of the Exeter

City Police.

Police

constables on parade in the old bacon-factory in 1959. They are

inspected by Frederick Tarry, former Chief Constable of the Exeter

City Police.

│ Top of Page │