The Leats of Exeter – a short history

Page updated 11th September 2017

Back to Quay and Canal

The growth of Exeter's

industrial trade from mediaeval times, and especially her serge

production, was dependent upon the supply of water power for the many

mills that lined the leats. However, the leats were not originally

built to supply mills with power, but were excavated for the draining

and reclamation of land between the city wall and the Exe. The banks of

the Exe under the wall were part marsh, part shingle banks, and were

covered twice a day by the tide until Isabel de Fortibus built her weir

at Countess Wear, that stopped

the tidal movement up the river, and closed the fledgling port.

The growth of Exeter's

industrial trade from mediaeval times, and especially her serge

production, was dependent upon the supply of water power for the many

mills that lined the leats. However, the leats were not originally

built to supply mills with power, but were excavated for the draining

and reclamation of land between the city wall and the Exe. The banks of

the Exe under the wall were part marsh, part shingle banks, and were

covered twice a day by the tide until Isabel de Fortibus built her weir

at Countess Wear, that stopped

the tidal movement up the river, and closed the fledgling port.

"The whole of these lands appear to have been gained out of the river, as large stakes are often discovered in digging, and the soil to some depth consists of strata of river sand and small pebbles. It is intersected by several branches and cuts from the river, very convenient for mills, dye-houses, &c. which occupy great part of it..." (Jenkins)

The river Exe at Exeter flows over a floodplain, and over the millennia the river has meandered from under the city walls across to Redhills, and back again. The river cliffs between Bonhay and the quay, were the only obstacle to further eastward movement of the river.

The First Leats

The marshy and sandy banks between the river and the city were drained in the 10th Century by the building of a series of artificial watercourses, including the Higher Leat, to form Exe Island; it was first recorded as 'insula Ex'. The island, bounded by the inner or Higher Leat, stretched from Head Weir below the Bonhay cliffs to the quay. Traces of a Saxon leat have recently been investigated by archeologists running next to the Higher Leat in Tudor Street. Shilhay was a broad shingle bank where the river curved from Exe Bridge to the quay.

By the 12th Century, Robert Courtenay, the Earl of Devon, owned this newly reclaimed land and proceeded to use it for industry and commerce. He let land along the leats for water mills to grind corn (grist mills) and for the fulling of woollen cloth. All the land along the leats were gradually developed. In 1548, after a long dispute between the Earl of Devon and the City, Edward VI confiscated Exe Island and Shilhay from the Earl and gave them to the City.

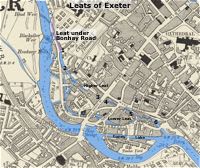

By the 19th Century, there were two main leats, the Higher Leat that was fed off the Exe at Head Weir and Blackaller Weir. The second was the Lower Leat which split from the Higher Leat below the Snail Tower on the City Wall. The Higher Leat flowed just below the City Wall, while the Lower Leat flowed parallel with Bonhay Road, under the mediaeval Exe Bridge to the south of St Edmund's Church and joined the Higher Leat just to the rear of the Custom House on the Quay.

A third water way named Coney Lake, formed the island of Shilhay. Coney Lake was cut around about 1820 to form a sort of canal, making Shilhay an island off Exe Island. There was not enough water flow to drive a wheel, but it was wide enoughh for small boats.

Managing the Leats

The leats were managed by a Committee of Mill Owners and a Captain of the Leats, who were elected at an annual meeting. Minutes of the meetings were kept from 1825. The Committee met in various public houses including the Cattle Market Inn, the Valiant Soldier and the King's Arms and in more recent times, the Moreton Inn in Cowick Street, or the offices of William French & Son next doo. The beds of the leats belonged to the City Council, which was consulted in matters concerning the maintenance of the leats. The cost of work was calculated pfor each mill owner, depending upon the number of mills he ran, and the length of leat needed to serve them. During the 1930s and 40s, when the gates were lowered so the leat bed could be cleaned and rubbish removed, they used prisoners from Exeter Prison.

The leats were drained once a year, for a week, for maintenance. The Committee also had to regulate the flow of water so that the river did not suffer in times of drought. In 1874, the City Council requested that the water be allowed to flow over Head Weir every Sunday, to oxygenate the river water during a drought. Between 8am and 8pm, every Sunday, for seven weeks the fenders were lowered to divert the river water over the Head Weir. In 1923, an Act of Parliament designed to safeguard the salmon and trout fisheries also required the mill owners to lower the fenders every Sunday, and on those days on which the mills were not working.

In the twentieth century both William French and George Shears were Captain of the Leats. George Shears still held the post after Head Weir Paper Mill closed to be replaced by the Mill on the Exe.

Weirs Raise the Water

Weirs are needed to keep the water raised to provide a head of water for the leats. The Head Weir or Callabere Weir was the first to be built to supply water to the Higher Leat. Records do not exist for Callabere before the 16th Century, but it was probably built at the same time as the Higher Leat in the late 13th Century. Small weirs and additional gates were installed along the leats, especially where they joined another, to allow the flow of water to be regulated, especially in time of flood. Short leats from the Exe to the Lower Leat were built, to either provide yet more power, or to regulate the water flow. The City Brewery near the Exe Bridge was powered by a small water course tapped off the Lower Leat at Horse Pool.

The weirs were the responsibility of the City Council, and in 1864, the mill owners sent a petition requesting that remedial work be done to the Head Weir; the middle of the weir was several inches below that of the sides, reducing the head of water to the leats, and the power of the mills by 19%.

Blackaller Weir was built to supply water to the Head Weir Paper Mill (now the Mill on the Exe) and additional water fed into the Head Weir leat.

In 1694 a Water Engine was built, just above the entrance of the Blackaller Leat. Large, 18 inch wooden pipes were installed between the water powered engine and a 600 hogshead capacity (40,000 gallons) lead cistern that was at the back of the Guildhall.

"....an act of parliament was procured, and an engine for that purpose erected (at the head of the new leat) on a very ingenious model, which, notwithstanding the elevated situation of the city, plentifully supplies (by the help of wooden pipes) such inhabitants who, on the payment of an annual rent, are desirous of being furnished therewith." (Jenkins) This water supply became redundant when the Pynes Water Works was opened in 1835.

The leats provided an obstacle to the building of New Bridge Street in the 1770's to join up with the new Exe Bridge.

"In some places it was necessary to elevate the ground near forty feet, in order to form a level; and arches were turned over the mill leats and avenues into the Island and Bonhay. At the bottom of Fore-street, directly in the way of the intended opening, stood the tower and remains of the parish church of St. Hallows on the Walls, which was taken down " (Jenkins)

There were additional smaller leats connecting the Lower Leat with the Exe, and joining the Higher with the Lower Leat. In the early 20th Century, large sections of the leats were visible from bridges, the rear of buildings and cuttings, while other sections were covered by mills and other buildings. The building of the modern Exe Bridges and the cut of Western Way from Southgate down to the bridges resulted in the Lower Leat being filled in. Renslade House is built right across the course of the Lower Leat. Coney Lake was also filled in, the industry moved to Marsh Barton, and Shilhay redeveloped for housing in the 1980's.

Sources: Jenkin's Civil and Ecclesiastical History of the City of Exeter, Isacke's Remarkable Antiquities of the City of Exeter, 1049-1677, Exe Island and the City Brewery by Geoffrey Pring. © 2006 David Cornforth - not to be used without permission

3 – the Upper Leat behind the old Mission Hall (Plumb-In Centre).

4 – looking back to where the leat emerged from under the floor of this arched cellar. Photo courtesy of Melvyn Hill.

The dipping steps where the Upper Leat enters Cricklepit Mill. Leat Terrace above is just to the right, off camera.

│ Top of Page │