- Home

- Memories

- Scrapbook ▽

- Topics ▽

- People ▽

- Events

- Photos

- Site Map

- Timeline

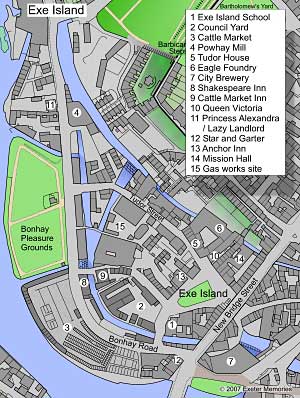

Exe Island is the land between the river and the Upper Leat. It stretches from Head Weir just above the Mill on the Exe to beyond Cricklepit Mill. The area covered in this history is the land north and west of the old, mediaeval bridge. Refer to the West Quarter and Shilhay for the southern half of Exe Island.

Up to the 10th Century, the area consisted of a mud and shingle bank covered with reed and grass, which flooded when the river was high. Small channels dissected the bank, which would gradually move over the years. The late Saxon population of Exeter drained the bank by digging leats. It was the digging of the Upper Leat that created'Insula Ex' as it became known in the 12th Century.

Exeter's traditional Lammas Fair may have been held on Exe Island - however, by the time of Domesday in 1086, it had moved to the Crollditch, or Southernhay and the tradition is uncertain.

It was the the Barony of Okehampton, later to become the Courtenay's, who took possession of Exe Island and Shilhay after the Norman invasion. Sometime between 1180 and 1190, Robert Courtenay granted to Nicholas Gervaise "...all his water which Thomas the fuller holds of him outside the west gate of Exeter, which is between his corn mills and Crickenpette, so that the said Nicholas and his heirs may build a mill on the said water towards Crickenpette as shall appear best and most commodious to them". And the first of the many mills to line the leats of Exe Island was built.

Exe Island had become the industrial quarter of Exeter by the end of the 12th Century, with woollen fulling and corn mills, tanneries, dye houses, bronze foundries and a healthy wine trade with the continent through Exeter quay. Exe Bridge was built by Nicholas and his son, Walter Gervase and opened around about 1240, complete with St Edmunds Chapel that would eventually become the parish church of Exe Island.

At the end of the 13th Century, Isabel de Fortibus, a Courtenay, built Countess Wear which restricted shipping to the quay, damaged the salmon fisheries, and caused much bad feeling with the City. A generation later, Hugh de Courtenay escalated the animosity by blocking the weir completely, and building a quay at Topsham to dominate trade to and from Exeter.

The Courtenays expected a certain amount of deference from their tenants and it was recorded that ".... whensoever this Lord, the Earl of Devon, cometh into Exe Island the tenant for the time being is to come seemingly apparelled, with a napkin about his neck, or upon his shoulders, and a pitcher of wine, and a silver cup in his hand, and shall offer his Lord thereof to drink." (Jenkins) And so, the Courtenays swaggered through the next 250 odd years, lording it over their lands.

By the 16th Century cloth-finishing was the most important industry on the island, and the time when the Courtenays grip upon their lands in the Exe Valley was weakened. On 31st December 1538, Henry Courtenay forfeited many of these lands to Henry VIII for treason, and also lost his head for his trouble. In 1549 Edward VI granted Exeter Exe Island and Shilhay to the City Chamber. The Chamber appointed a bailiff to Exe Island, the city Chamberlain, John Hooker, becoming one of the first. Hooker was an influential man in the city, and his appointment indicates how important Exe Island and its industry was to the city merchants.

It was in June of the same year that Edward granted Exe Island to the city, that there occurred the Prayer Book rebellion, when several thousand Cornishmen and others, laid siege to Exeter, occupying Exe Island, St Thomas, St Sidwells and other suburbs. A protestant messenger for Lord Russell, named Kingwell was captured by the horde and hung from a tree on Exe Island. After Lord John Russell relieved Exeter on 6th August 1549, and defeated the rebellion, troublemakers were rounded up, including Robert Welshe, vicar of St Thomas. Welshe had supposedly stirred the rebels and was implicated in the hanging of Kingwell. Welshe was tarred and hung from his own church tower, his body not to be taken down until the accession of Mary, four years later.

An important development for Exeter was the building of the city's water engine in 1694, on the leat at Head Weir. A water wheel turned a pump which supplied water through wooden pipes to a large, lead cistern at the back of the Guildhall. This tank relieved the supply from Headwell Mead, or Lions Holt which supplied the Underground passages - Waterbeer Street is probably named after the water carriers who supplied pails of water to householders from the Guildhall Tank.

Water was a pretty dodgy substance at this time, swimming with bacteria, and not very wholesome. Therefore many preferred beer, knowing that they were less likely to get a bad case of gippy tummy. Robert Vilvayne, a physician purchased in 1657, from the Mayor and Chamber a piece of land in Exe Island for a public brewhouse and malthouse. Many who know Exeter from before 1970 will remember his brewhouse as Norman and Pring's, City Brewery. Just a couple of years later, the famous Tudor House in Tudor Street was constructed, and is a very early example of the use of local brick in part of its structure.

The woollen industry flourished after the civil war, and Exe Island's fulling mills were running at full capacity, with most of the open ground devoted to rack fields for drying the woollen serge. In the 18th Century, it became apparent that the old bridge was not sufficient for the city and plans were drawn up to construct a new crossing. It was decided that a direct link to Fore Street would be preferable to the old route through the West Gate, and in 1778 both the new, three arch bridge and New Bridge Street opened. Exe Island was effectively cut in two by the new viaduct and the only arched tunnel under New Bridge Street between Exe Island and Frog Street joined the two sides. Other openings were made through the viaduct, for the Upper and Lower Leats to flow.

The rack fields became redundant with the loss of the woollen trade to competition from Leeds and other northern cities at the end of the 18th Century. They weren't empty for long for Exeter's first gasworks was completed by 1817, on a site adjacent to Bonhay Road, close to the modern Renslade House. At this time, Bonhay Road did not exist. A short road from the bottom of New Bridge Street petered out after a couple of hundred yards to a footpath. The much wider river bank was a pleasant, grassed space that had been used for many years by locals for leisure. However, the 19th Century industrial development of Exe Island between the two leats also saw part of the river bank developed. After the Higher Market was opened in 1838, the cattle market that had been held within the city moved out to the river bank, opposite Renslade House. Late in the century, the Bonhay Pleasure Ground was created, with a small lodge for the park keeper. Bonhay Road was cut through to St David's Station by 1863.

Brass and iron foundries soon followed the gas works into Exe Island. The site of Renslade House was the West of England Foundry, with the Bonhay Foundry filling the gap between it and the gas works. On Tudor Street, behind the gas works was a slaughter house, providing a service for the cattle market, while behind the Tudor House was one of the last dye houses in the city; this became the brass and iron foundry, the Eagle Works, opened in 1864 by William Martin. He had previously been a partner in Parkin and Son, who had a foundry on the other side of Tudor Street. Powhays Mill was situated at the point where the Upper and Lower Leats branched; it had long been a grist and fulling mill. Changing times meant changing uses, and by the 20th Century it had become an ice works, only to burn down before the Second World War.

It was not all industry in Exe Island - a thriving community lived in Tudor Street, while three alleys led off the central square that was named Exe Island on the maps. There was Anchor Lane, which led to Anchor Square, later named St Edmunds Square. There was also Rosemary Lane and Saddlers Lane, each lined with small terraced houses, and squeezing past the sides of the foundries and gas works. At the Bonhay Road end of Rosemary Lane, just inside the Lower leat could be found the Cattle Market Inn, which along with the Shakespeare Inn just around the corner, provided the foundry and cattle market workers with a place of refreshment. Just to the side of, and below, New Bridge Street there was the Exe Island School, built in 1873 as a mixed and infants school.

Along with the West Quarter, Exe Island was a pretty dire place to live. In times of flood, drains would overflow, spewing bloody water from the slaughter house, across the streets and no doubt, into houses. In 1869, a report stated that the smell from the 'Gas Ammonical Liquor Distillery and Manure Factory' was a public health danger in the Bonhay. This was a 19th Century, industrial, Dantes Inferno with disease and poverty alongside the foundries effluent heavily polluting the air.

The gas works was closed in 1878, which probably went some way to improving the air of the island. In the 20th Century, industry closed or moved to Haven Banks, while the cattle market moved out to Marsh Barton in 1939. The West of England Foundry was replaced by a Council Yard which housed Exeter's shire horses. During the Second World War, there were two air raid shelters for 100 people situated in Exe Island, along with a British Restaurant that served some, by all accounts, dodgy food.

From the 1950's onwards, Exe Island has seen almost all of its industrial buildings demolished, Renslade House was constructed in 1971 on the old Council Yard, while St Edmunds Square was replaced by a large, steel warehouse type building and carpark. The Tudor House was restored in the 1970s and along with the buildings on each side, the Queen Victoria pub, and the Plumb-In Centre, which was the Mission Hall, nothing remains of old Exe Island. Western Way cuts through the centre of Exe Island, through the site of the old school, to emerge from under New Bridge Street into the destroyed Frog Street - but that is another story.

Sources - Exeter City Time Trail website, Jenkin's Civil and Ecclesiastical History of the City of Exeter, various maps and other articles on this website. All photographs kindly supplied by Alan H Mazonowicz unless stated otherwise. Map by David Cornforth. This article is © 2004/7 David Cornforth and is not to be used without permission.

Exe

Island in 1905.

Exe

Island in 1905.

Exe

Island and the Frog Street tunnel under New Bridge Street. Courtesy of

Dick Passmore.

Exe

Island and the Frog Street tunnel under New Bridge Street. Courtesy of

Dick Passmore.

Warehouse

in Tudor Street, circa 1970. This building still exists.

Warehouse

in Tudor Street, circa 1970. This building still exists.

Pubs of Exe Island Anchor Tavern Inn From 1782

onwards, the inn annually celebrated Lord Rodney's victory over the

French. The landlord had his son christened George Rodney to honour his

hero - it was listed in 1816 with its last listing 1923 - since

demolished. Situated in Exe Island square.

Bell Inn This inn was in

existence on Exe Island in 1569 according to Jenkins. May have been

situated on the Exe Bridge.

Blue Anchor First listed in

1833 in an inventory of the City Brewery, with Edmund Foster as

landlord for a term of 99 years. It was also mentioned in a City

Brewery inventory of 1844. Position unknown.

Cattle Market Inn The Flying

Post has a report from 1842 of a burglary at the Cattle Market Inn. It

also had a To Let notice in 1844. First listed in 1844. It closed in

September 1968 and was demolished for road widening. Situated just

inside the Lower Leat, in Rosemary Lane

Lazy

Landlord/Princess Alexandra First listed in 1878 as Princess

Alexandra, and listed in Kelly's 1972. It was closed by the brewery in

May 1982 and then re-opened as the Lazy Landlord. In 2000 it was

finally closed, and in 2002 demolished and replaced with apartments.

Queen

Victoria First listing was in 1844. It has been refurbished and

become a popular pub for students and locals alike.

Round Tree Inn First appears in

a Brices Weekly advert dated 1727 - first listed 1816, and last listed

in 1897. The Roundtree was noted as a large inn in Frog Street,

opposite the tunnel to Exe Island. It ceased trading in 1903. The Round Tree Mill, Exe Island was named after the inn.

Shakespeare Inn First listed in

1889, last listed in 1967, demolished in 1967 for road widening.

Situated on Bonhay Road, on the opposite side of the leat from the

Cattle Market Inn.

Star and Garter First listed in

1878 and closed 1929. Demolished in 1933 for road widening. Situated on

New Bridge Street, on the corner of Bonhay Road.

Tudor Street

and the Tudor House, circa 1970.

Tudor Street

and the Tudor House, circa 1970. The Doss House was between the Anchor and Queen Victoria. This rare

colour photo was taken just before it was demolished in the 1960s.

The Doss House was between the Anchor and Queen Victoria. This rare

colour photo was taken just before it was demolished in the 1960s.

Renslade House.

Renslade House.

│ Top of Page │